The Museum of Everything was established in 2009 as a one-off exhibition championing work by artistic underdogs. Since then it has quickly grown into a regular fixture on the international art scene...

The Museum of Everything was established in 2009 as a one-off exhibition championing work by artistic underdogs. Since then it has quickly grown into a regular fixture on the international art scene, including shows in Italy and Russia. On the eve of a major presentation at the inaugural London art fair Frieze Masters, and the Museum’s first exhibition in Paris, AnOther caught up with Museum founder and director James Brett to discuss, well, everything.

How did a one off exhibition turn into a permanent, albeit constantly changing, ‘Museum’?

Our first exhibition, which was supposed to be a small project that ran for a few weeks, ended up staying open for four months and had 35,000 visitors. It made us realise that there must be something in it. So we took the show to Italy, and then we did a small show at Tate Modern, then the following year we co-curated a show with Peter Blake. And then finally we toured our mobile museum around Russia, advertising artists who are not artists. We also curated a pop-up show at Selfridges, where we showed work by artists with learning disabilities, but we didn’t talk about it, we just put the art out there. It seemed like a radical idea, but why can’t Selfridges be a museum and why can’t shoppers be an audience? We had 100,000 people, and really we hoped to challenge conceptions of what art is and who can be called an artist.

The international art world is full of galleries, museums and institutions, established to showcase artists’ work. What makes the Museum of Everything different?

The Museum of Everything is an activist project, it’s a friendly radical. We present the work and let people make up their own minds. As it evolves the museum seems to take on a life of its own. It started off just as a show and now it’s feeling more like an idea, a philosophy.

Is the experience of working with artists who are untrained or not represented by a commercial gallery different from working with those who are?

I think gallery representation is a bit of a red herring. Many seem to be masking a fundamental truth, which is that art can be made without justification or a destination. People are naturally creative from birth, but the idea of ‘art’ as we often know it, in the context of the commercial art world, can seem quite divorced from that fundamental practice of making. As a museum we are primarily interested in artists not just because they have taught themselves, but more because they have found a unique personal expression which is private to them. It think that’s why many of the artists who come into contact with our exhibitions connect with the work that we show, because it connects with the fundamental reason that they originally began creating.

"The Museum of Everything is an activist project, it’s a friendly radical. It started off just as a show and now it’s feeling more like an idea, a philosophy."

When showing work by artists that many people haven’t heard of, do you think that aligning yourselves with institutions such as Tate help your audience to take you seriously?

I personally believe that most art institutions often don’t know how to present this type of work, which comes from an inability to consider these artists are the same as others. I would go so far as to say that most museums operate on a segregation policy, but often don’t realize they are doing it. I think the role of the Museum of Everything when working with a major institution is to show an alternative.

This year you are exhibiting at the inaugural Frieze Masters, an art fair that focuses on art from the Ancient to the Modern. What was it that made you want to be part of it?

We’d been thinking a lot about the art market and how it relates to museums, and it seemed to us that many museums consider themselves to sit outside of the concerns of the art market and the demands of collectors, which we feel is just not true. The process of acquisition of artworks is fundamental to the creation of art. Because of Frieze Masters’ focus on historical work we also wanted to communicate this alternative history of art to a wider audience and collectors who perhaps hasn’t come to our shows.

Unlike your larger shows that often show hundreds of artworks and artists, you are only showing two at Frieze Masters – how did you select them?

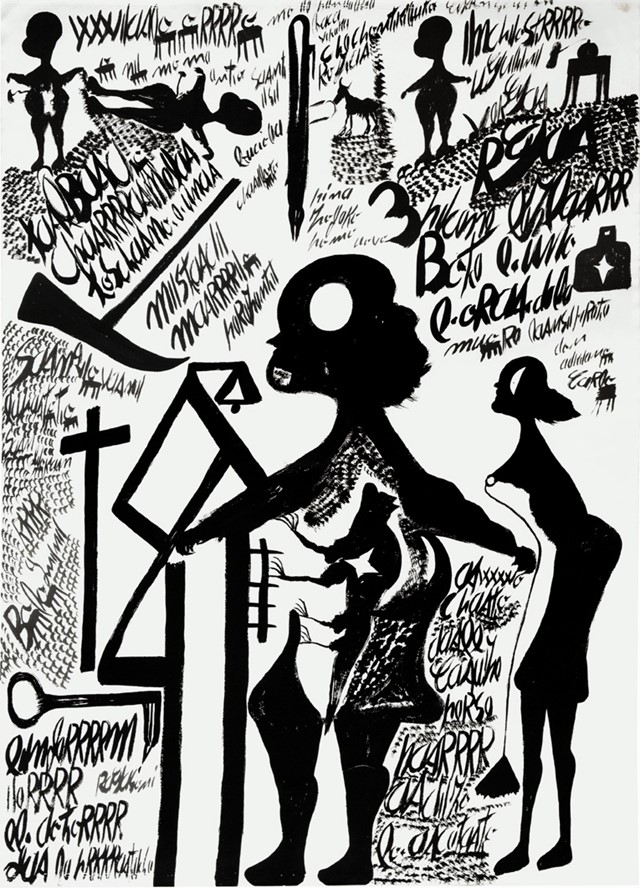

We isolated two artists, Carlo Zinelli and William Edmondson, both artists who we felt had had a strong impact on modern and contemporary art, and at the same time no impact, and were undervalued and unappreciated by museums, curators and collectors. Zinelli was an Italian artist who suffered with severe shell shock after the Spanish Civil War, and was left unable to communicate. He began to paint, and produced over 3000 works, which were, in effect, an autobiography of his life, via very bold abstract images. The paintings were brought to the attention of the artist Jean Dubuffet, which gave him visibility at the time, but he then disappeared. The work really reveals the complexity of the war and it seems so relevant today. It also seemed like a great chance to show his influence on Debuffet, which was quite strong. Edmondson was an African American from Tennessee, who began his artistic career by carving railroad sleepers into figures, African American icons, and so on. His work eventually came to the attention of Alfred Barr, the director of MOMA in New York at the time, who fell in love with them. Barr then gave him a solo show at the Museum in 1937, but people took offense and it was buried. Today, very few people know about Edmondson, and his pieces never gained the significance that they should have.

The Museum of Everything will be at Frieze Masters between October 11–14.

Text by Siobhan Andrews