As part of Parallel Voices, a recent programme of dance, movement and sound performances in London, a series of artists from varying disciplines came together to show and discuss their work, and collaborate.

As part of Parallel Voices, the recent programme of dance, movement and sound performances held at the Siobhan Davies Studio in London, a series of artists from varying disciplines came together to show and discuss their work, and collaborate.

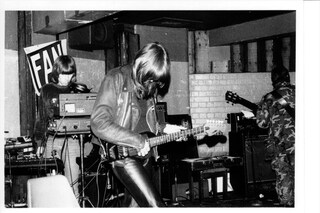

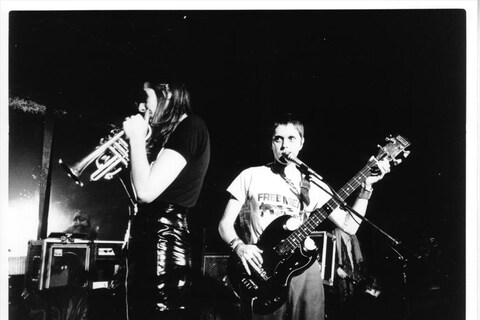

Curated by electronic sound art pioneer Carsten Nicolai (who recently composed the music and light performance for the Calvin Klein A/W10 collection show), Parallel Voices included contributions from Throbbing Gristle’s Cosey Fanni Tutti and Chris Carter, Ryoji Ikeda who is a label mate of Carsten’s on Raster Noton and a regular collaborator, and legendary German industrial act Einsturzende Neubauten’s Blixa Bargeld.

We brought together Carsten, Cosey, Chris and Siobhan, the studio’s founder and auteur of movement and choreography to discuss how, and why, they make the work they do.

How would you define the difference between sound art and music?

Cosey Fanni Tutti: It depends whether you define music as sound, which I have difficulty with. I regard music as something quite alien to what I do.

Carsten Nicolai: I think these categories are irrelevant when you are making the work; they only become relevant once it is distributed. It’s the need we have to put something in a box.

CFT: Well it’s the age-old question, “What kind of music do you make?”

CN: People assume that if you’re working with sound then you're creating something they can relate to, but often I work with frequency and people do not consider that music.

Siobhan Davies: Is that about culture educating the ear?

CFT: People are taught how to interpret music from an early age. They are taught scales, choruses and hooks. If you hear something that doesn’t fit the categories you have learnt to assimilate, you end up lost.

Do you choose to use the word “sound” over “music” to allow the listener to be open?

CN: We choose any way of describing our work, when we have to, to give us the largest range.

How important is performance to you?

Chris Carter: We would find it very difficult to do what we do if there wasn’t a live element to it.

CFT: You make completely different sounds live, and in the studio. You’re on the fly; there is no second chance on stage.

CN: I use totally different tracks, with entirely differently developed sounds. I’m a little more aggressive and pronounced live.

SD: Does that come from the urgency?

CFT: It is so much about the rapport with the audience, the push and pull that you have with them.

CC: I like it when things go wrong, the adrenalin surges and you make it up on the spur of the moment.

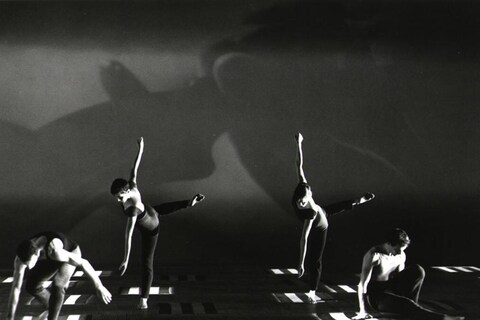

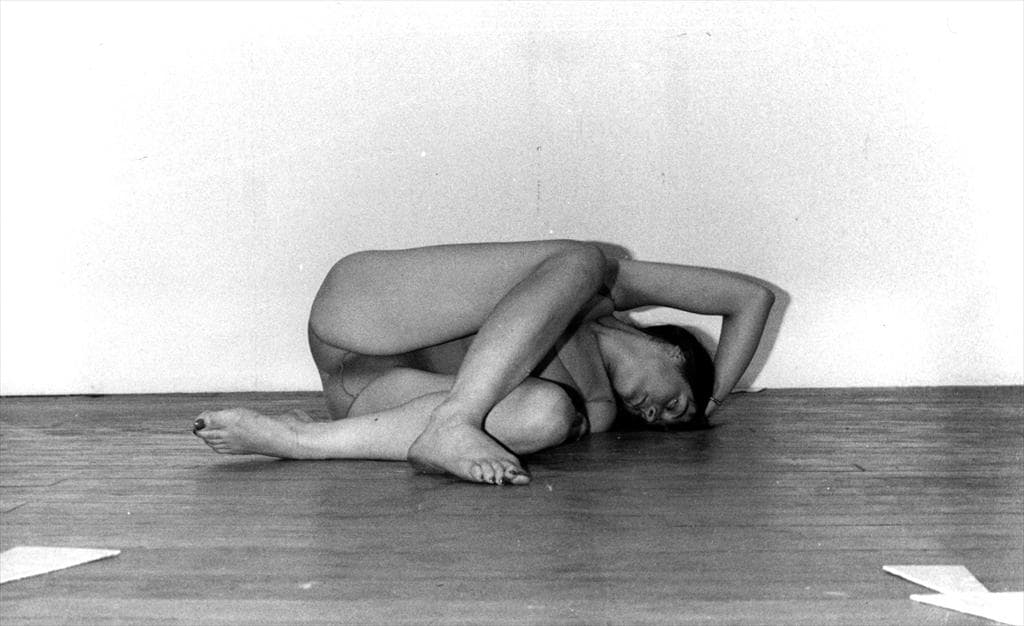

SD: I remember performing a piece in a gallery space, continuously throughout the day, whether there was an audience or not. We had to think about how to react when people were in the space, when they first arrived, and more importantly, how not to be thrown by their influence.

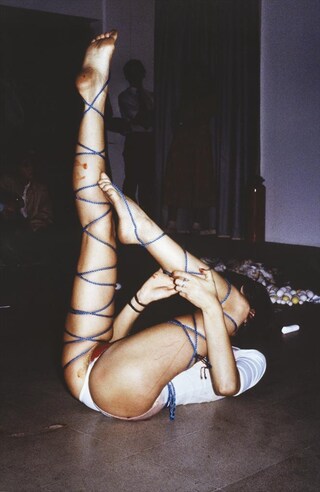

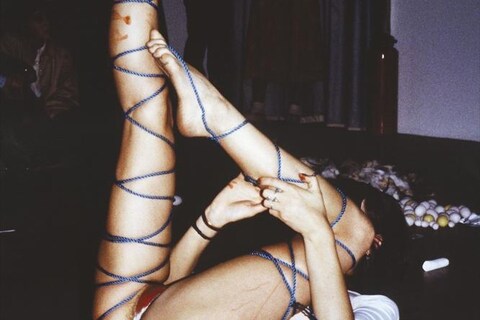

CFT: It sounds similar to performing my art actions in the Seventies and Eighties. I didn't want it to become a them and us situation. When the audience throws something into the work, you take it, use it, and throw it back out.

CC: Sometimes literally.

CFT: Absolutely!

CC: Carsten, is your visual live?

CN: Yes, visuals are really important to me. When I am performing it is mostly just me on stage, with an interface and a computer. I am a static object so I started creating visuals to illustrate what was happening inside the machine, and inside me.

The other commonality between everyone here is collaboration. Why is that so important to you?

CFT: You always reach a point where there are a lot of directions you could go. With another person involved you go somewhere completely new and make choices you may not have done. Also, when you have been playing with someone for a long time you become so involved in his or her way of thinking, that you perform intuitively. With Throbbing Gristle I often perform, as does Genesis (P-Orridge), with my eyes closed. We open them at a particular point, make eye contact, and know we are going to move on with the track. You must know that feeling from dance Siobhan?

SD: There are a couple of people, one in particular who I have worked with for over twenty years. We really push each, and we agree and disagree openly because we trust each other. It’s very hard when you propose an idea and someone replies, “Are you sure?”

CN: I used to have a teacher whose first reply, once you had answered a question in class, would be “Are you sure?”

CFT: I never answered in class because I was always worried I would be wrong.

WO: You used to doubt yourself? That is interesting considering the level of improvisation in your work now. Do you ever doubt your work?

CFT: I don’t think it’s a doubt about the work you are doing, or the work you have done. You change so much that the work produced when you’re younger, or the things said, are at odds with what you would do, or say, now. I read something recently that referred to this idea of freedom and responsibility. The idea was that when you're young you have an unnerving energy and a complete freedom of responsibility to strive forwards. In the middle period of life you invest in what you have already begun; you fill in the gaps. You produce the work and let it find its place. After that you again feel that original freedom of responsibility, to experiment. That’s how I feel at the moment, a sense of great freedom and responsibility; creating work simply for people to address and consider.

SD: What is it you want people to consider?

CN: Art is not made for the audience to consider. It is made simply because the artist has a genuine need and desire to make it. What you are making should only be made to be relevant to you personally. But when you make a piece of work that is honest and authentic, then it can speak to others.

William Oliver writes for Another, AnotherMan and Dazed & Confused and recently contributed to exhibition catalogues for Adam Neate’s show, A New Understanding and Rankin's Cheeky book of erotica photography