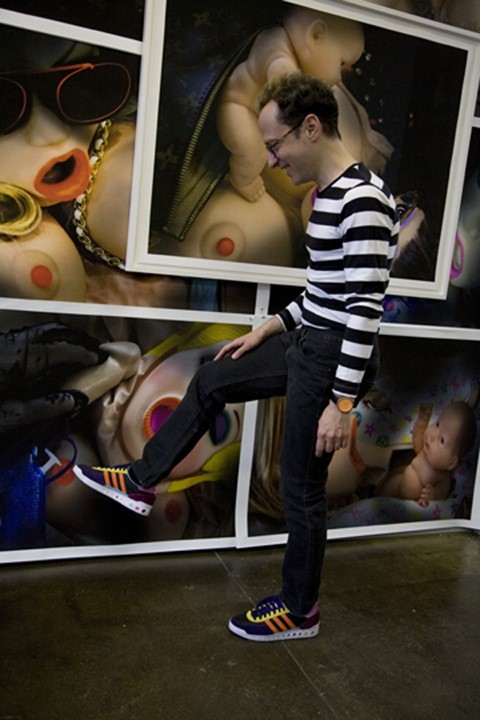

The latest subject in Donatien Grau's column, Wayne Koestenbaum is a leading voice amongst American poets and cultural critics...

Wayne Koestenbaum is a leading voice amongst American poets and cultural critics. Equally acclaimed for his poetic measure and his critical daringness, his writings include iconic essays exploring the aesthetics and ethics of celebrity, such as Jackie Under My Skin: Interpreting An Icon (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1995); or Andy Warhol (Lipper/Viking, 2001); another part of his work is devoted to the gay creative process: The Queen's Throat: Opera, Homosexuality, and the Mystery of Desire (Poseidon, 1993). He also redefined the interaction between the literary self, reflexive discourse, and the art of fiction, in books such as Hotel Theory, and, more recently, Humiliation. He serves at Distinguished Professor of English at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

How would you connect fashion to elegance?

Elegance is Art Nouveau, Matisse’s lines, Miró; elegance is a formal property concerning the duration, intensity, and consistency of line. Fashion, on the other hand, is not about line; fashion is about time, contemporaneity, a person’s punitive arrival into the now. Although we imbibe fashion from sages, magazines, and stores, when we adopt fashion for our own, it can become an explosive intervention. Fashion has nothing to do with whether it looks good, or whether it’s useful. The equivalent of fashion is a best-seller. Elegance, however, is wily and original, like Mallarmé’s syntax. In a global moment of capitalism, or postcapitalism, we are interpellated by economic forces so much larger than us that "fashion" as a category of value is ruined.

What is the role of history and art history in your conception of fashion?

I have a very reductive and absolute sense of the history of fashion: before Christ, and after Christ. Suddenly, around 1920, a new epoch began in women’s fashion. I don’t when the new epoch arrived for men: maybe it was in the 1960s, or with Calvin Klein underwear. To bring art and fashion together, let’s isolate one element: "colour". Think of Klee’s Tunisian watercolours. Or Mondrian. Klee and Mondrian (and others) created a chromatic discourse that still circulates. When you walk by the window of Gap, or a row of American Apparel underwear, you enter an aesthetic universe coterminous with Gustav Klimt. Our everyday aesthetic experience has been branded or copyrighted or clarified by great names in art history. I see clothes through art: when I put my "grid" cap on, I see the world through Klimt, Klee, Agnes Martin, Donald Judd. Colours have citationality. Fashion doesn’t happen merely season by season, like the supposedly forward march of history; fashion depends on categories—not timeless, but not entirely temporal—that organise the way we see the world. And to understand the structures of the visual we have to look to art history, because artists branded optical pleasures, just as novelists branded the idea of romantic love. Novelists didn’t invent love, but they made it comprehensible.

"To understand the structures of the visual we have to look to art history, because artists branded optical pleasures, just as novelists branded the idea of romantic love"

Would you describe fashion as a language and a discourse, as Barthes did it?

I’ve never read his book on fashion. It’s the only book of his that I’ve never read. I’m afraid to read it. If we think of language as a completely random, disorganised, aleatory system of sounds, and not as a national location-related body with structures that police it, then yes, fashion is a language. It’s not a language in the way a president’s speech is a language, or in the way the cut of meat we call "beef" is a language. Cow, as produced by culture, is a language. To call fashion a language seems to punish (and circumscribe) its freedoms.

The word "intellectual" was coined in a time of great political distress. Does fashion have a political role? And in which way?

If we think of gender as amorphous until society articulates it, then fashion is one of the major sifters through which the unmarked body enters politics. Fashion is our armour, chains, corset. Fashion is a lacerating reminder of how little choice we have about gender. On the other hand, fashion is a site of play, anarchy, deviation; through clothing, we stage appropriations that allow fashion’s imprisoning structures to drift away from their origins. Take "pants": in classic gay culture from the 1960s, all it took was a specific handkerchief in a pocket to turn a pair of working class jeans into a secret signifier of a sexual phantasmagoria. In my book Cleavage, I note that cleavage is natural but also constructed. All the places on the body that clothes don’t cover up are places that fashion seems to abandon, although those naked zones are precisely where fashion still plays its heavy hand.

What does fashion have to do with intellectuality ?

I have not mastered the difficult nomenclature of woman’s fashion, which includes lots of specific words: the different kinds of fabric, the fashion designers. It’s like studying for a graduate school qualifying exam in 19th century poetry: you have to memorise facts, and you have to understand the stylistic distinctions between Verlaine and Rimbaud. You have to understand the forms they worked in, and why. Even what in Yiddish we call a "Schmatta" contains multitudes and mysteries of terminology; I don’t know the names of a schmatta’s specific underlinings, its noun-rich nuances.

"Style is the boat that cuts through the waters of fashion. Even if it sinks."

How would you relate the concept of "fashion" to the one of "style" ?

"Style" is an honorific category, but I do think that any human being has a style, even if it’s an absence of style, or a failure of style. Style is a fingerprint, a signature: as in phrenology, that discredited pseudo-science, style suggests a specific, readable configuration of the brain. If fashion is the network of choices available at any historical moment, then style is an individual’s system of navigating fashion’s turbulence. Style is the boat that cuts through the waters of fashion. Even if it sinks.

You have worked thoroughly about the making of icons. What part does fashion play in the construction of an icon?

An icon is a person of distinction, aura, and reputation, known for the intangibles that surround her like a cloud: although iconicity is based on fog and miasma, it also depends on specific fashion elements. Consider Andy Warhol’s wig, which was a failure of elegance, a solution to cover a lack of hair. "Wig" was how Andy made himself recognizable. Without that wig, we’d lack a clear sense of who Andy was. Icons have a satisfying recognisability of hair, physique, physiognomy; they dress with a juicy repleteness.

You have also worked a lot on gay identity. Is there a relationship between gayness and fashion? And if so, what is it?

In New York, gay people are often good-looking. That’s a fact. Non-gay people are good-looking, too, but one of the pleasures of living in a city like New York is male beauty’s tendency to signify gayness. A straight man who looks elegant looks gay, even if he’s not. That’s a major frisson—seeing a fashionable straight man. It’s as if he has a caption tattoed on his forehead "Imagine me in a gay sex act". An exciting declaration! Sexuality on the streets of New York is divided between gay and non-gay—that is, between availability to the visual pleasure of the passer-by, or unavailability to the visual pleasure of the passer-by.

In two weeks Donatien will be interviewing the gallerist, artist, editor and style icon Iké Udé