Ned Beauman investigates what the chances really are

If you are a zoologist who goes out looking for unicorns in the hope that you can sell off their powdered horns for some sort of male potency tonic, you probably do not find yourself the toast of your faculty Christmas drinks. But somehow, if you are a mathematician who goes out looking for a sure way to win at gambling – equally implausible, equally greedy – you can still be respectable. The man who invented card-counting in blackjack, for instance, was Edward O. Thorp, a professor at the University of California, Irvine. And two other mathematicians who both died on today's date – Abraham de Moivre in 1754 and Ada Lovelace in 1852 – are only the more fascinating for their trips to the casino.

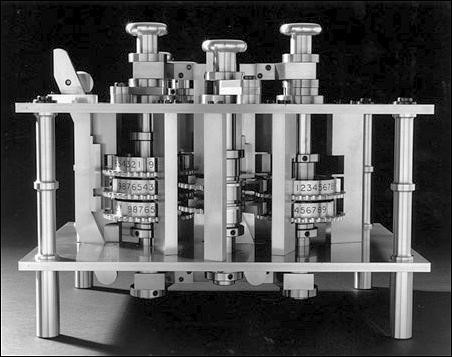

Lovelace, the only legitimate daughter of Lord Byron, started a gambling syndicate with Florence Nightingale's dad, using mathematical strategies of her own invention. Her biographer Benjamin Woolley suggests two reasons why she might have done so: either to pay off previous gambling debts (a hilariously bad idea), or to invest in the construction of her collaborator Charles Babbage's Analytical Engine, which would have been the first ever mechanical computer. A century earlier, de Moivre, a Frenchman who moved to London and became friends with Isaac Newton, wrote the first ever textbook on probability, The Doctrine of Chances, which sets out to 'gratifie the curiosity' of gamblers who 'engage in Play, whether from a motive of Gain, or merely Diversion'. Note to de Moivre: it's usually Gain.

But de Moivre was also famous for correctly predicting the date of his own demise. He apparently noticed that, in his old age, he was sleeping fifteen minutes longer every night, and from this he could work out the first night when he would sleep for twenty-four hours – in other words, forever. In fact, his combined interest in probability and death makes him the godfather of the modern actuary, and his name still comes up in life insurance textbooks. Meanwhile, one might say that Lovelace's contributions to the birth of computing make her a plausible godmother. But Lovelace (who did, unusually for a woman of the time, take out a life insurance policy on herself) died of uterine cancer at only 36. She had already tried to apply mathematics not just to horse-racing but also to the human nervous system and to the composition of music – if she'd lived long enough, might she have investigated mortality? I wager she would. Perhaps most of us aren't as morbid as de Moivre; but once you've realised that stern maths might help you put up a fight against the horrible randomness of the roulette wheel, then it's no stretch to hope that it might do the same for life and death.

Ned Beauman used to be Commissioning Editor at Another Man, writes often for Dazed & Confused and has also contributed to the Guardian, the Financial Times, and many other publications. His debut novel Boxer, Beetle will be published by Sceptre in August 2010