“What is it, [Art Nouveau]?... Art can never be new.” A new book celebrates Alphonse Mucha's lasting legacy – but it's one he didn't want to leave behind in the first place

Who? The voluptuous female figures, the elaborate handcrafted typefaces, those pastel hues: these were the features of Alphonse Mucha’s Art Nouveau posters which so excited Paris at the turn of the century. Growing up amidst the Czech National Revival movement in the 1860s, passion for his country influenced Mucha from boyhood. But it was Catholicism which inspired him in his earliest years. His first known artwork was a pencil sketch he drew at the age of eight, entitled Crucifixion, and it was later, whilst staring at a mural by Jan Umlauf in church, that Mucha’s vocation to become an artist was born.

In the years that followed, he honed his craft, illustrating satirical magazines and designing theatrical sets. When wealthy landowner Count Eduard Khuen-Belasi hired him to paint a mural for his home, Emmahof Castle, Mucha earned himself a sponsor. He went on to train at the Munich Academy of Fine Art in 1885, the Académie Julian in 1887, and the Académie Colarossi in 1888.

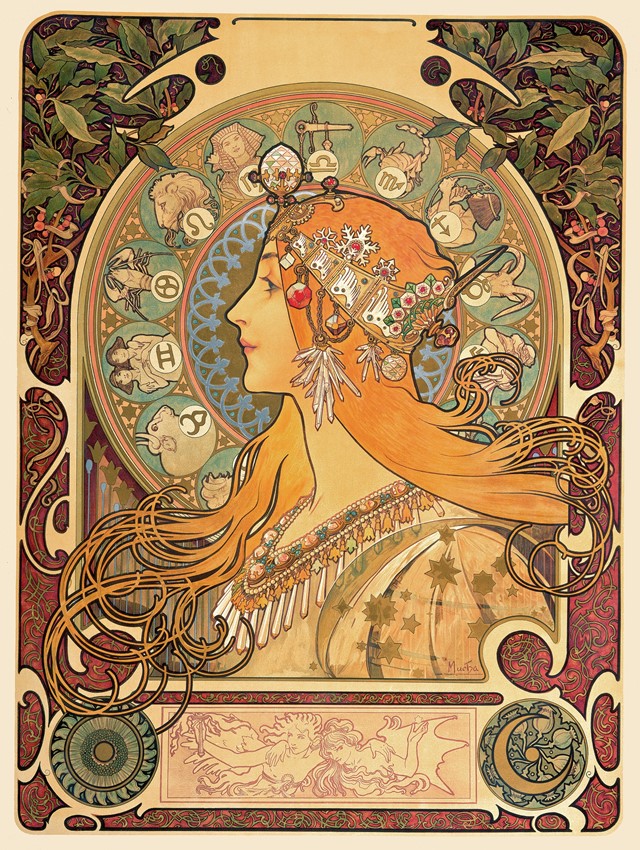

When the Count withdrew his support in 1889, Mucha had to return to illustration. He gave lessons in his studio, classes so successful they became known as ‘Cours Mucha’. But it was a last-minute commission in 1894 that altered the course of his career forever. He was asked to design a poster for a new production of Gismonda, directed by and starring world-famous actress, Sarah Bernhardt. The resulting image was iconic – Bernhardt as a Byzantine noblewoman, adorned in a golden and blue gown with a pastel pink orchid crown. It drew heavily on Mucha’s beloved Slavic heritage – traditions he believed were rooted in the Byzantine period – and it turned him into an overnight sensation.

Poster design, thereafter, became Mucha’s remit; his daring creation for cigarette company JOB featured a highly sensual image of a woman smoking, and it was arguably his most acclaimed commercial work. But beyond commerce, Mucha was very much a ‘thinking’ artist. He went on to create such works as Le Pater (1899), an illustrated book examining the Lord’s Prayer, and The Slav Epic (1928) – 20 grand canvases charting the history of the Slav people; imagined to unite his homeland, it was widely considered his greatest creation.

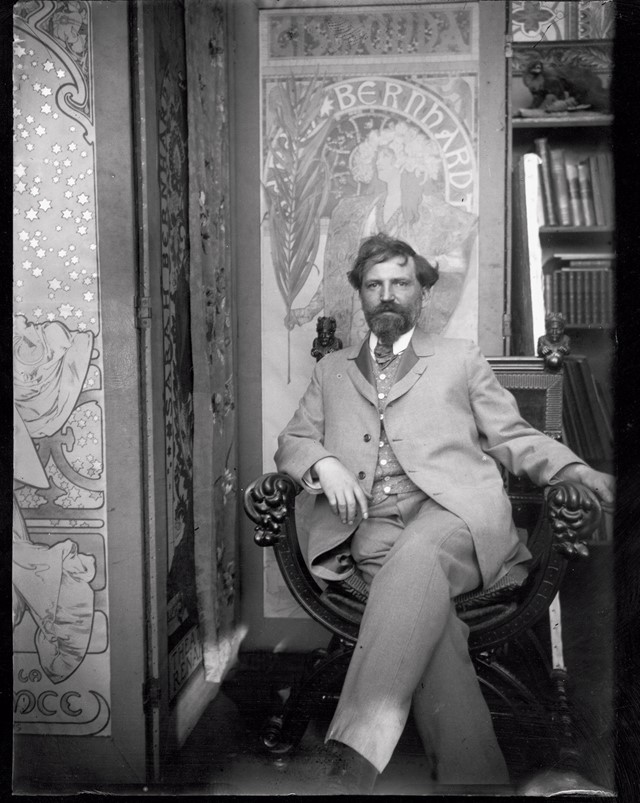

What? Jewellery, packaging, interiors, set design, photography, sculpture – there is little Mucha did not turn his hand to. His impressive body of work has been photographed for the hardback catalogue, Alphonse Mucha, edited by Tomoko Sato. The exquisite tome details how Mucha’s Art Nouveau came to sit alongside his other works, which revealed his staunchly patriotic, yet also utopian, ideals. It tells the tale of a struggling artist who earned his crust via commercialism, which enabled him to explore the far reaches of his creative vision. A reality to which many artists today can, no doubt, relate.

Why? “What is it, [Art Nouveau]?... Art can never be new,” said Mucha, as recorded in his autobiography, Alphonse Mucha: The Master of Art Nouveau, and it is ironic that he should be remembered as the master of a style he spent his career distancing himself from. For Mucha, art was constant, not a fashion. Expressionism, surrealism – none of these movements interested him. It was his native Slavic traditions, folklore, spiritualism – these were the things that he turned to for inspiration.

Described by his son, Jiri Mucha, as “more of a philosopher than a painter”, whilst his commercial works earned him fame (and a living), their production did not excite. “I saw my path as lying elsewhere, somewhere higher,” he said. “I was looking round for means to spread light that would reach even into the remotest corners.”

Fundamentally, Mucha was influenced by two ideologies: nationalism (the progression of his country) and freemasonry (which advocated the progression of mankind). His devotion to his homeland was conveyed through such pieces as The Slav Epic (which took over 15 years to complete), and his dedication to portraying the cornerstones of humanity – Reason, Wisdom and Love – were developed through a, sadly unfinished, triptych named after the three. Together, they reveal the profound philosophy of a man so ironically remembered as ‘Master of the Commercial Poster’.

Alphonse Mucha, edited by Tomoko Sato, is out now, published by Skira.