As a new exhibition exploring the influence of Caravaggio upon his followers and the birth of Caravaggism opens in London, we present some lesser-known information about the master of realism and psychological drama

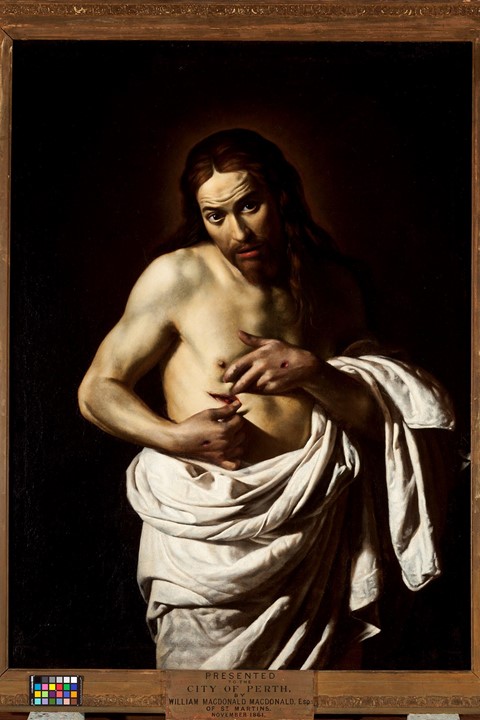

Over 400 years after his death, the paintings of Italian Baroque pioneer Caravaggio remain as affecting, groundbreaking and influential as ever before. He painted with an inimitable sense of realism, his figures, whether common card sharks or Biblical heroes, sporting torn robes, dirty fingernails and highly individualised faces that convey remarkable psychological depth. He approached traditional themes (from still lifes to holy scenes) with breathtaking originality, blurring the boundary between the sacred and profane. Moreover, he was an extraordinary storyteller, whose theatrical use of light and shade (or chiaroscuro) and propensity for zooming in on the defining moments of a narrative still have the ability to stun viewers in an age of tabloid sensationalism and high-intensity Hollywood dramas.

Last week marked the opening of a new exhibition at London’s National Gallery, titled Beyond Caravaggio, the first UK display to consider the impact of Caravaggio’s defining traits on his contemporaries and followers. The show presents a small but potent handful of the artist’s works among many more by the Italian, French, Flemish, Dutch, and Spanish artists he inspired in order to explore the artistic phenomenon known as Caravaggism – the international clamouring for work both by and in the style of Caravaggio following the artist’s death in 1610 until the mid-17th century. It is a fascinating exhibition that highlights just how major and enduring an effect Caravaggio has had on the history of art. Here, in celebration of the show’s unveiling, we present 10 weird and wonderful facts about the visionary artist.

1. Caravaggio’s real name is, in fact, Michelangelo Merisi da (or “of”) Caravaggio, Caravaggio being the small town in northern Italy where the painter was born, and hence derived his nickname.

2. Caravaggio’s childhood was seeped in tragedy. He lost many family members to the plague that swept through Milan in 1557, when he was just six. In October of that year, it claimed the lives of his father, grandfather and grandmother within the space of three days and five years later he was orphaned when his mother also died. Caravaggio – who was then apprenticed with the painter Simone Peterzano in Milan (an alleged student of Titian) – would continue to be haunted by the dark events of his youth thereafter.

3. During his years spent in Milan, Caravaggio is said to have encountered some of his most important early influences by way of the city’s great masterpieces. These included Leonardo’s The Last Supper and various works in the regional Lombard style – the striking naturalism of which is thought to have had a profound effect on the young artist. He is also presumed to have voyaged to Venice during this period, as his early work suggests a distinct familiarity with the exquisitely lit paintings of Giorgione and Titian.

4. The artist was famously short-tempered and prone to violence. As Caravaggio expert Andrew Graham-Dixon wrote in an article for the Financial Times, “he lived his life by an elaborate honour code, with specific insults punishable by particular injuries. When a Roman waiter questioned [his] taste, he responded by smashing a plate into the man’s mouth. When a young painter insulted him behind his back, Caravaggio stalked him by night and then attacked his rival from behind with a sword.” Indeed, it was an early incident of “certain quarrels” that caused Caravaggio to flee from Milan to Rome in mid-1592. It was there that he would gain his most important patrons and develop the style that would see him dubbed “The most famous painter in Rome” by the early 1600s.

5. While Caravaggio’s extraordinary brand of realism would later become one of his most celebrated traits, at first it was much frowned upon – his subjects, replete with wrinkles, squints and defects, were a far cry from the fashionable idealism of Michelangelo. His contemporary Francesco Scannelli, accused him of creating paintings of “terrible naturalism ... astonishing deceptions, which attracted and ravished human sight”. Caravaggio achieved such naturalism by the controversial employment of models from the lower echelons of society, including vagrants and prostitutes – much to the horror of those who recognised such characters assuming the guise of the Virgin et al.

6. Another element that would become a signature attribute of the painter was the inclusion of himself in his works. Young Sick Bacchus (1593), for example, is widely believed to be based on a young, sick Caravaggio painted during a period of convalescence, while the gruesomely severed head of Goliath in David with the Head of Goliath (c. 1605-10) bears the artist’s features. He is also believed to be the lantern-bearing figure in the far-right hand corner of The Taking of Christ (c. 1602) which features in the National Gallery exhibition.

7. Almost any art fanatic knows that Caravaggio is one of the most important pioneers of the chiaroscuro technique; from relatively early on in his career, almost all of his works boast a single, main light source, illuminating the action like a spotlight. But a new and lesser-known theory has emerged that he may have used a camera obscura-like device (ie. “a darkened box with a convex lens or aperture for projecting the image of an external object onto a screen inside”) in order to achieve this. David Hockney, who describes Caravaggio as having “invented Hollywood lighting”, believes the artist to have used a mirror to reflect the image of a model standing in bright light into a darkly lit room.

8. Caravaggio was fiercely competitive and famously scathing of his artistic rivals. As his contemporary Giovanni Baglione once noted, “At times he would speak badly of the painters of the past, and also of the present, no matter how distinguished they were, because he thought that he alone had surpassed all the other artists in his profession.” One amusing example of how this quality manifested itself in Caravaggio’s work can be seen in his great masterpiece The Conversion of St Paul (1600) in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome. As Graham-Dixon explains, “[it] was painted in direct competition with Annibale Carracci, whose saccharine Assumption of the Virgin still hangs over the altar. To stress his disdain for Carracci’s brand of vapid magnificence, Caravaggio contrived a cunning insult: the rump of St Paul’s proletarian carthorse is pointedly turned to the face of Carracci’s Madonna.”

9. Two brutal combats proved the most pivotal moments in Caravaggio’s lifetime. The first was a fight between the artist and Ranuccio Tomassoni, purportedly over the latter’s unfaithful wife. During a pre-scheduled face-off, Caravaggio murdered Tomassoni and was outlawed from Rome and forced to flee to Naples. He worked in Naples for a number of months before seeking work in Malta, subsequently fleeing to Sicily after yet another brawl, and finally returning to Naples. There in 1609, he himself was brutally attacked by an unknown assailant, supposedly hellbent on revenge from a prior assault. He was slashed across the face and badly wounded, an injury from which he never fully recovered. The artist died in 1610, aged 39. It is believed he was attempting to make the journey back to Rome.

10. Caravaggio’s influence reaches far beyond the realm of Caravaggism and can be felt in the work of countless artists working today, from photographer David LaChapelle to painter Peter Doig. Martin Scorsese has widely credited Caravaggio with inspiring his oeuvre, quoted in Graham-Dixon’s book Caravaggio: A Life Sacred and Profane as saying, “I was instantly taken by the power of [Caravaggio's] pictures. Initially, I related to them because of the moment that he chose to illuminate in the story.... You come upon the scene midway and you're immersed in it… It was like modern staging in film: it was so powerful and direct. He would have been a great film-maker, there's no doubt about it. I thought, I can use this too.”

Beyond Caravaggio is on display at The National Gallery until January 16, 2017.