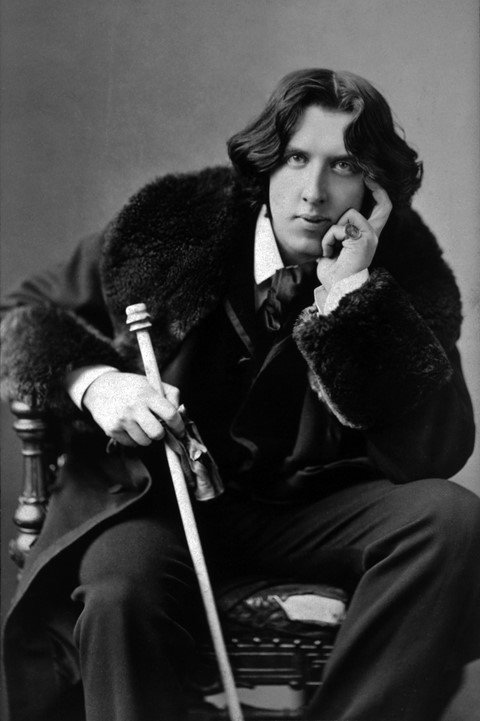

As a new exhibition at Reading Prison sees the likes of Patti Smith read from his seminal work De Profundis, we consider the groundbreaking impact of Wilde's unjust persecution

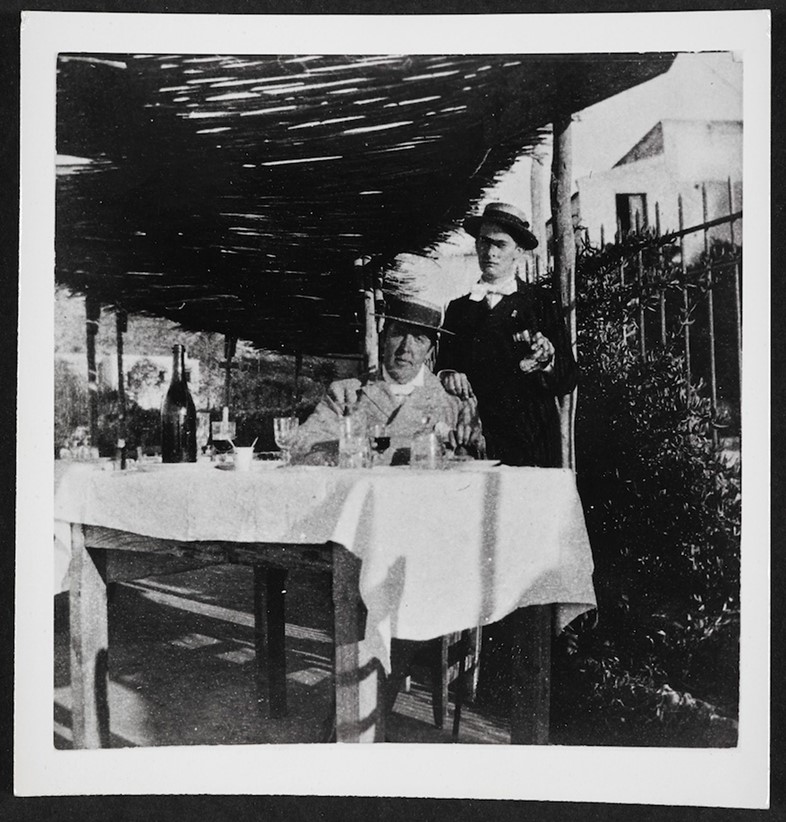

The story of Oscar Wilde is a brilliant, tragic and complicated one; a tale that, despite many efforts, can’t easily be transformed into simple fridge magnet epithets stating that “We are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars.” Aside from being eminently quotable, Wilde’s legacy is vital in both the literary sphere and in terms of his impact on gay rights and culture. To cut a long and heartbreaking story short, in 1895 – just a few months after the debut performance of his masterpiece The Importance of Being Earnest – Wilde was sent to prison convicted of “gross indecency”. Wilde had tried to sue Sir John Sholto Douglas, father of his lover, Alfred Lord Douglas (or Bosie), for libel after a series of homophobic insults, culminating in a note left at Wilde’s club the Albemarle reading “For Oscar Wilde, posing somdomite [sic].”

The tables soon turned on Wilde, and evidence was brought forth of his “gross indecency” – or homosexuality – something the writer had at turns been trying to hide, for obvious societal and legal reasons, and also attempting to garner more public acceptance and respect for. The court transcriptions are a testament to Wilde’s courage and unfailing, unflappable wit. In the reading of letters between Wilde and Bosey, it was in the courtroom that the chilling and resonant euphemism for homosexuality, the “love that dare not speak its name,” was coined. When questioned about its meaning, Wilde said: “It is that deep spiritual affection that is as pure as it is perfect. It dictates and pervades great works of art… It is beautiful, it is fine, it is the noblest form of affection… The world mocks at it, and sometimes puts one in the pillory for it.”

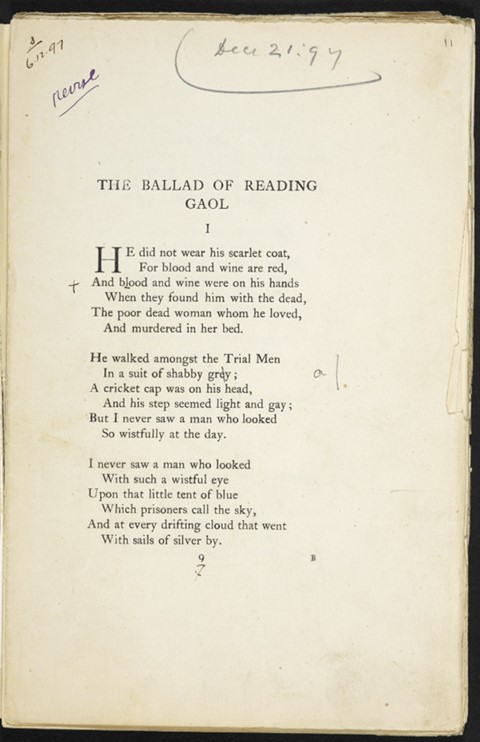

Wilde’s steadfast belief in his own sexuality, and his subsequent martyrdom for it, have made his writings all the more vital for the homosexual community after him. Homosexuality was not made legal in the UK until 1967, and voices like Wilde’s provide both comfort and hope in the face of injustice, ignorance and hatred. “To regret one's own experiences is to arrest one's own development. To deny one's own experiences is to put a lie into the lips of one's own life. It is no less than a denial of the soul,” Wilde wrote in his powerful unsent letter De Profundis, created in prison and part love letter, part treatise on spirituality, the self and religion.

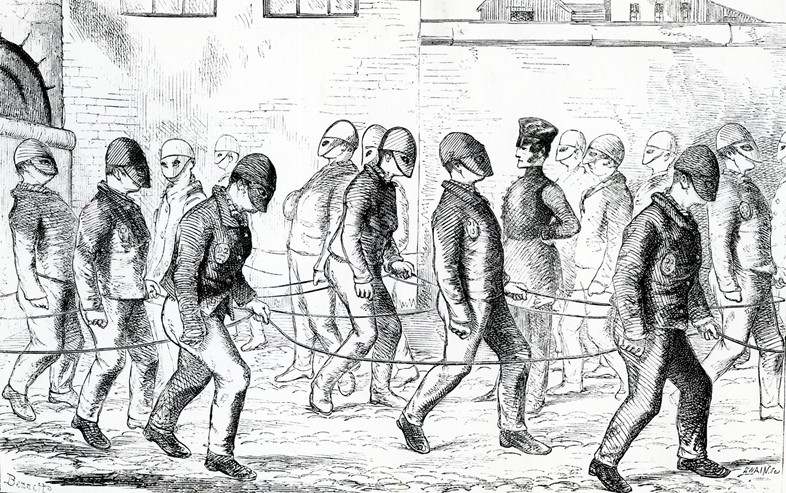

A new exhibition orchestrated by arts group Artangel will delve back into this potent prose time and time again, in the very place it was written – Reading Gaol. Entitled Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison, the show sees the jail space, which closed in 2013, house a series of installations by artists including Marlene Dumas, Nan Goldin, Steve McQueen and Wolfgang Tillmans. Each day, De Profundis will be read in its entirety by speakers such as Ralph Fiennes, Maxine Peake, Lemn Sissay and Patti Smith; while visitors to some cells will find newly-penned letters the theme of state-enforced separation by writers including Binyavanga Wainaina, Ai Weiwei, and Anne Carson.

Such a stellar cast further underscores the vital legacy of Wilde on art, forging paths in self-acceptance and ideas of the personal as political. We spoke to Artangel co-founder Michael Morris to find out more.

On why people still love Oscar Wilde…

“It’s about his work and about his life, which are inextricably linked. His plays have always been popular and I think people identify with him for living a flamboyant life in Victorian times. He feels very modern; his aphorisms and epigrams feel like they could have been written yesterday.

The form and content in Wilde’s work are conjoined, it’s very contemporary humour and use of irony, and he as a contempt sensibility. He feels close to us in terms of era, but it’s 116 years since he died. It doesn’t feel like that in his work or when you read about him, and that’s no more true than in De Profundis. It’s a kind of soul-searching and it wouldn’t have happened had he not been in prison under the separate system, so his prison sentence changed the tone of his writing.”

On Wilde’s legacy for the gay community…

“His fall from grace was so dramatic and so unprecedented, so that also plays a part in what we remember about him. He’s a martyr to the cause, but in De Profundis he doesn’t write about his sexuality openly – there were hints, but it was definitely euphemistic. He’s a gay icon, but he’s definitely not a gay rights campaigner, and it would be anachronistic to expect people to talk about their sexuality openly then. He wasn’t afraid to tell it like it is, but he never discussed his sexuality in print, and it could seem striking that he doesn’t in terms of our modern sensibility. There’s been a huge revolution in sexuality, and it’s only recently that it was made legal in this country – in some countries, it’s still illegal. We want people to be mindful of that oppression and persecution.”

On how the nature of suffering in De Profundis shapes our reading…

“I don’t think you need to be gay to understand and appreciate and be amused by Wilde’s writing. It’s universal, it’s not partisan. There are many people, myself included, who are not gay, who are straight, who absolutely identity with what he went through. You don’t have to be gay to empathise. De Profundis’ intensiveness and obsessiveness is quite rambling because he was only allowed to write three pages at a time. That rawness and unfettered nature adds to its howl, its stream-of-consciousness.”

On how the arts have shaped gay rights and culture…

“There are cultural outputs that contribute to social tolerance. Art now in this country is much more accepted; when Artangel began there was a kind of fear of visual culture, and I think that changed with the Tate Modern. It became something exciting, and wasn’t marginal anymore. Art’s themes and way of undressing issues all contributed to an atmosphere of tolerance. It’s extraordinary that in our lifetime, gay marriage is accepted: it’s happened very fast – the distance between homosexuality being illegal and gay marriage is only a few decades, and it shows how far we’ve come in our tolerance and empathy to all kinds of relationships. I think contemporary art has contributed to that, but so has journalism and campaigning. They formed a coalition to show that of course it should be accepted and celebrated.”

On what we can expect from the exhibition…

“There’s a reason each artist was invited, it’s not arbitrary. There’s something about the environment that speaks to their work, and that their work speaks to. It’s a very powerful environment. All the readers have been asked to read De Profundis as themselves: Ralph Fiennes isn’t playing the part of Oscar Wilde, he’s reading it as Ralph Fiennes. We didn’t give the artists any brief, but we did decide early on that what struck us about the prison most was that quality of silence, so we decided not to have sound works. The prison itself is the first work of art.”

Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison runs from September 4 – October 30, 2016 at HM Reading Prison.