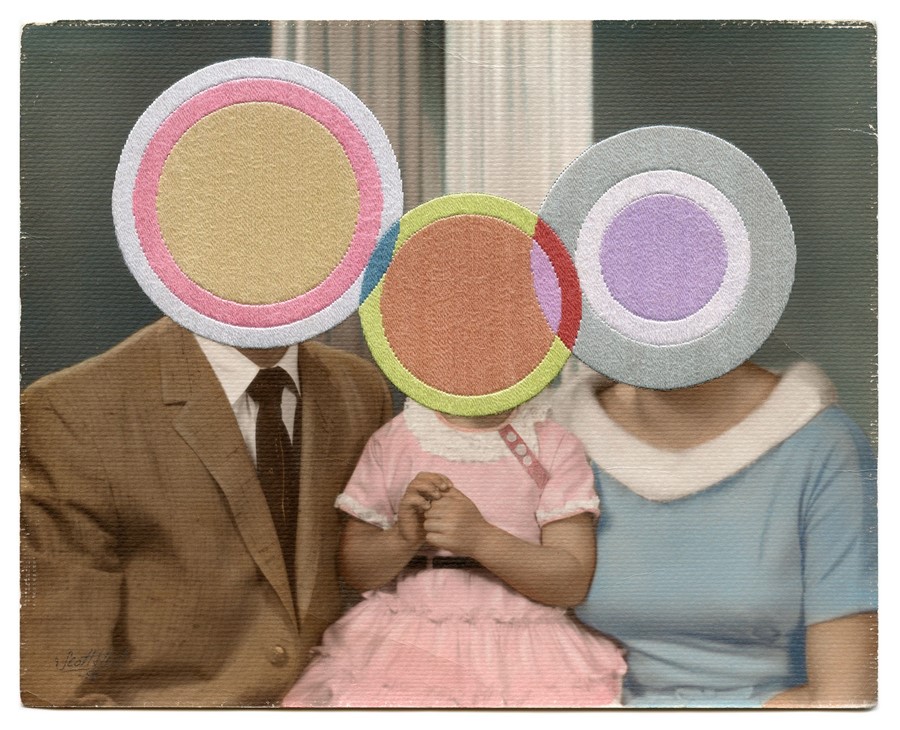

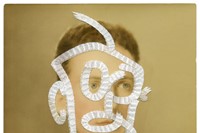

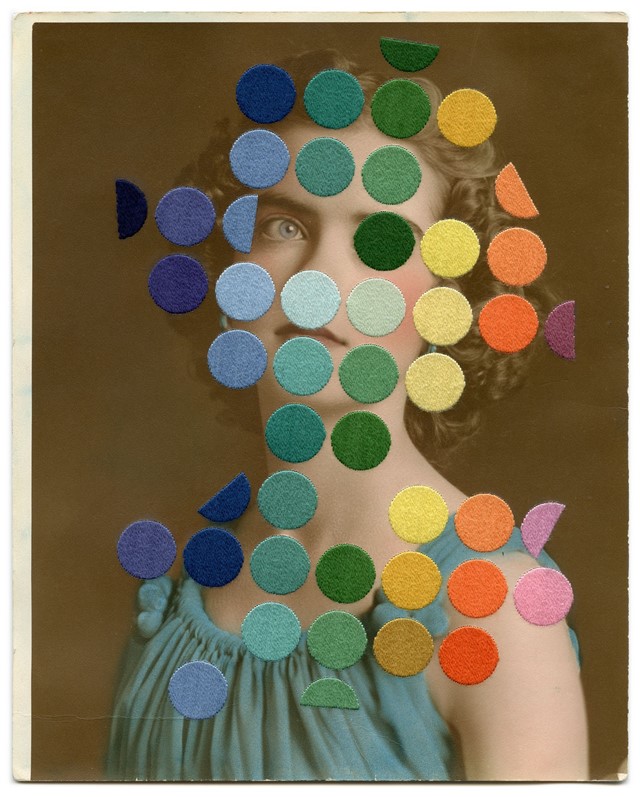

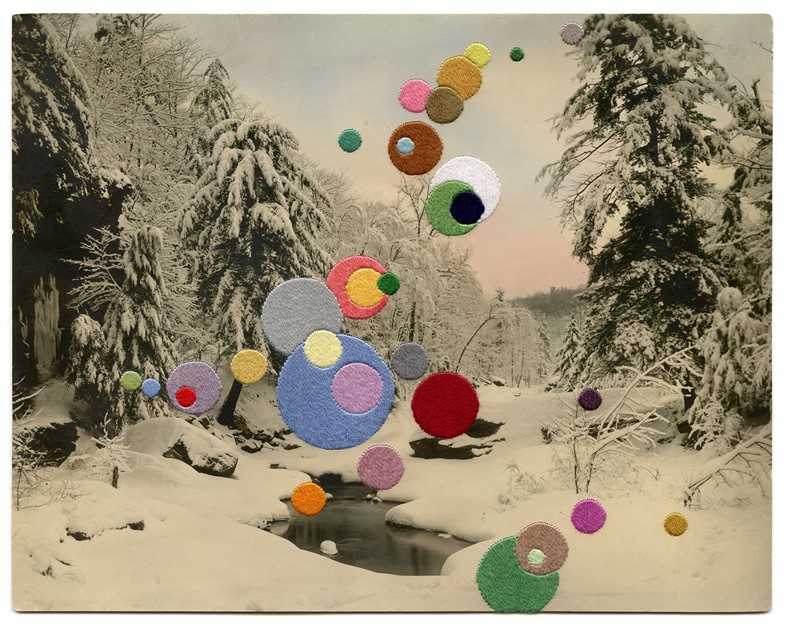

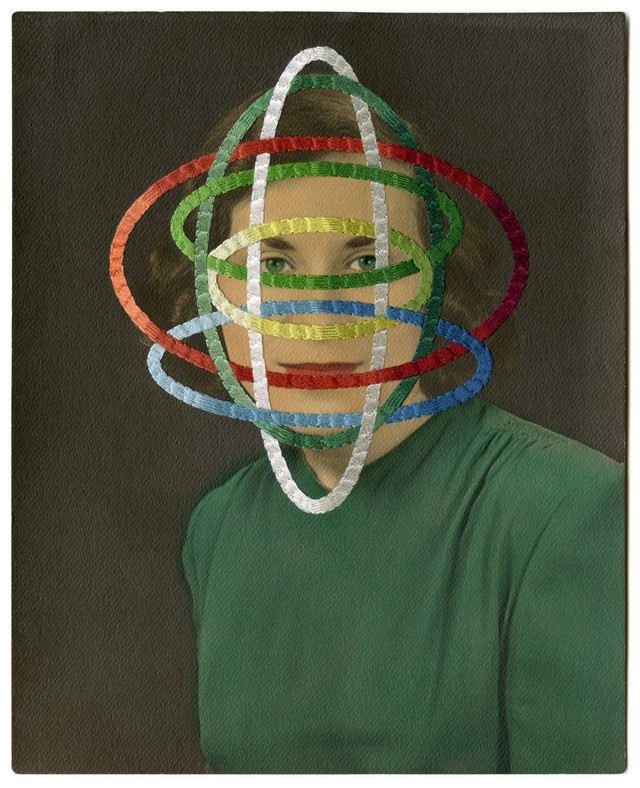

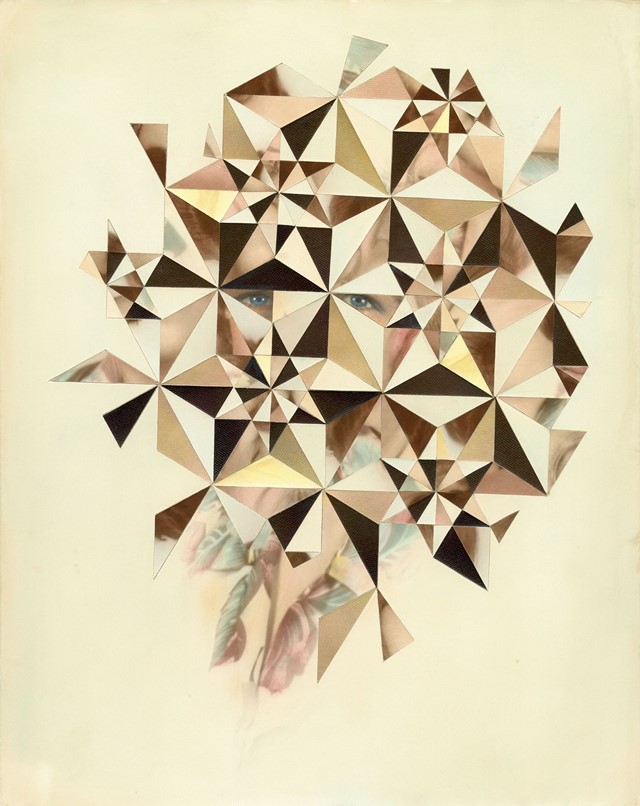

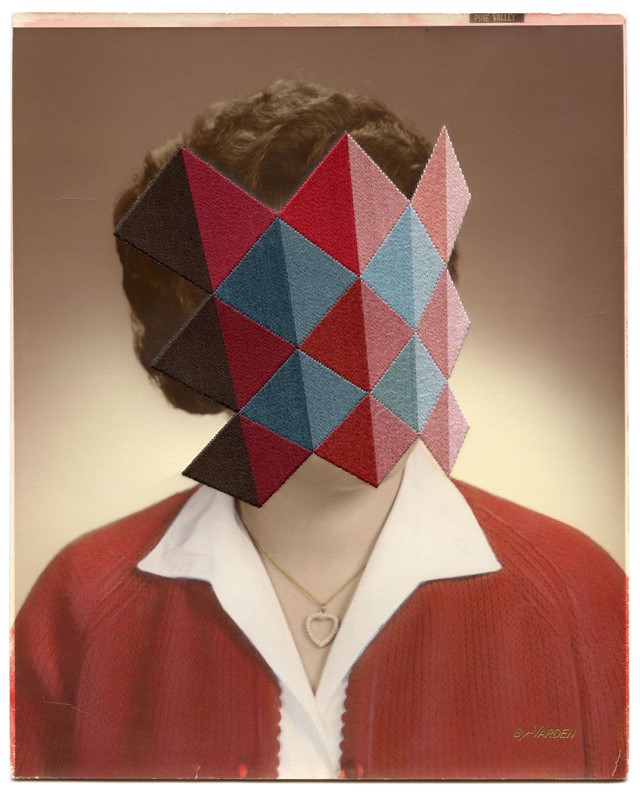

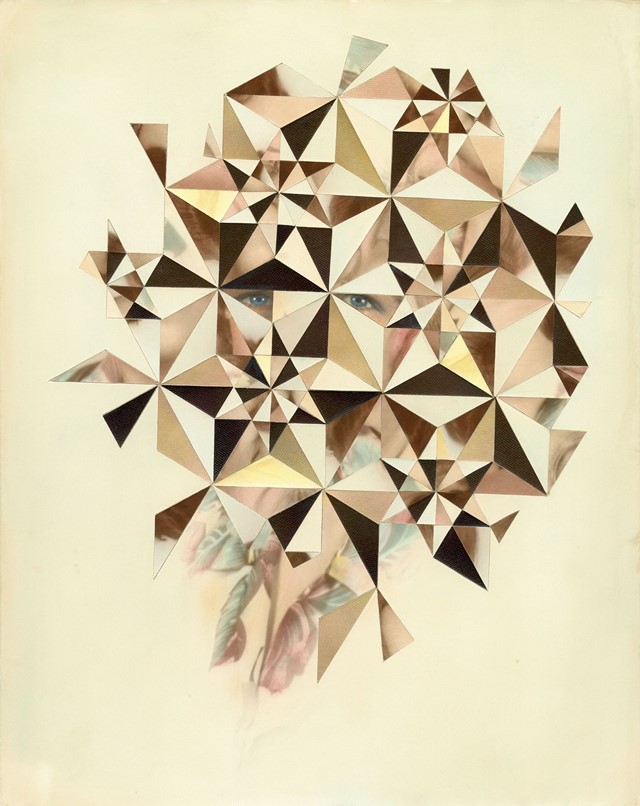

From embroidered colour spectrums to intricate geometric cut-outs, Julie Cockburn's awe-inspiring photographic manipulations grace no less than three major exhibitions this summer

"When I was young, my grandmother taught me how to embroider," says British artist Julie Cockburn, who has been applying layers of embroidery to found objects and photographs for several years. "As a child I was obsessed with those 1970s Spanish tourist postcards of traditionally dressed Flamenco dancers with physically embroidered skirts and waistcoats. I’m sure they have been an underlying inspiration for the work I make today." Cockburn trained as a sculptor at London's Central St Martins, where she was encouraged to dig around in the city’s skips for materials. It sparked a love affair with found objects and imagery that persists in the artist’s work today. "It’s the sense that you can respond to something with an unknown history in a subjective way."

This summer marks a busy period for the artist, who is currently exhibiting new works at group shows at Pôle Image, Rouen, (alongside John Stezaker, Hannah Whitaker and Lorenzo Vitturi among others) and at Flowers Gallery, London, delving in to the role and meaning of the photograph in the contemporary context, before opening a solo exhibition at The Photographers' Gallery this September. Ahead of this flurry of activity, we sat down with Cockburn to talk about about her experiments and interventions in the medium of photography, her love of found objects and photos, and her creative process.

On what guides her practice…

"I have been challenged by academics when I say my practice is intuitive, but I think there is definitely a truth in that. I am always drawn to photos and materials that have integrity – I suppose what I mean by that is that they have a truth and history in themselves – plasticine, embroidery threads, pom-poms, archetypal images of person or place. Collectively, we recognize and know them, so my use of the materials in a different context carries a particular weight. It’s the same with the photos. I choose archetypal ’portrait’ photos from the 1940s to 1970s – those that echo 18th and 19th century oil paintings, typically a head and shoulder pose. They are motionless studio shots, with space around them, both physically and emotionally, which allows me room to make my interventions. And the landscape photos I work with are typical, romantic. I suppose there is less of the original photographers’ own personality in these old photos. The subject invariably speaks for itself."

On the power of found photographs…

"Because I know what the original photos looked like before my intervention, it’s difficult for me to imagine seeing them for the first time with the collage or stitching in place. But I think there is pathos in the work. I generally find the photos from car boot fairs, junk shops or on Ebay, where they are sold as job lots or in house clearance sales. ‘Found’ object is a fitting term here; they have been lost from their original place and meaning. Often worn, dog-eared, stained and with a patina that gives them an unknown history, these photos have been on a journey over the last half century that I know nothing about. So I engage in a kind of storytelling when I am planning a new work – I react to the object itself, to the composition, colours, and my subjective response to the imagined character of the person or place I see in the original photo. I title the works when they are finished and I can see how my intervention has highlighted or exaggerated a physical or perceived characterisation."

On making something new out of something that exists…

"It’s exciting to engage with the response that found objects instill in me. Unlike painters, I am not faced with an intimidating blank canvas. Found objects start the conversation. I think that perhaps the fact that I use actual photographs in my work (at a time when photography itself is taking on a new dimension – particularly with the sharing culture of social media) has highlighted the nostalgia of the photograph as object. How great to have all ones photos on file, ready to crop, colour adjust and post online in a few seconds. But I miss my old photo albums and the paraphernalia that went with them. The guillotine, glue, corners, hand written notations and ‘stuff’ (pressed flowers, train tickets) that went in too. And the ceremony that surrounded the photo processing – that eternal wait before you could collect them from Boots to see if they had actually come out okay. Perhaps my work hints at all of that too."

On abstraction and figuration…

"I work with different series of works, and what I make next is often dictated by what I’ve just made. The collage and embroidery works can be laboriously time-consuming, and I sometimes need to do something different, more carefree and playful, to counterbalance this once I have finished a particularly intense piece.

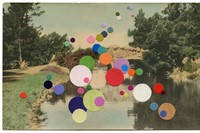

The Happenstance works evolved from a series of slightly over-exposed landscape photos I found, and to a large extent are an exercise in composition. However, the barely visible, but still existent, horizon line and the introduction of physical layers by sanding, cutting and embroidery means that they vacillate somewhere between abstraction and representation.

Having recently finished a group of embroidered portraits for an exhibition at the Centre Photographique in Rouen, I made an abstract painting in Plasticine that is showing in the John Moores Painting Prize in Liverpool. So my work has a rhythm of intense concentration and experimental play. I don’t see the works as that disparate either. I am using a personal, visual language to respond to specific materials and images that I have around me in my studio."

On presenting her work in the physical and digital space…

"Bizarrely, I feel a work is only complete when I have scanned or photographed it and I can view it on screen. I have no idea where this comes from, though I feel as though I can ‘see’ it better when I’m a step removed from the artwork itself. Likewise, I can better gauge compositional balance and tone by looking at a work in the mirror, the reverse image similarly in two dimensions. I think perhaps I get too close to a piece, particularly if I have been embroidering something for a couple of weeks. So that distance helps me to evaluate if it has worked out or not, and can hold itself.

I always think they look great in reproduction – in a magazine, catalogue, or online – and this is helped by the fact that my starting point was an image. Perhaps it’s a control thing; I can control the lighting in which they’re seen, the cast shadows etc, when I put digital images online. But I’m always surprised when I see the work in real life if I haven’t seen it for a while. Pleasantly surprised generally. And my greatest joy is seeing people peer closely at an original piece and appreciate the handiwork that’s gone into it. So there are pros and cons to both."

L'Autre visage, Portrait et Expérimentations Photographiques runs until October 1, 2016, at Pôle Image, Rouen. Out of Obscurity runs until September 3, 2016, at Flowers Gallery, London.