Canadian artist Vikky Alexander, who subverts fashion editorials in order to shatter consumerist fantasies, might be the most relevant critic of capitalism that you’ve never heard of

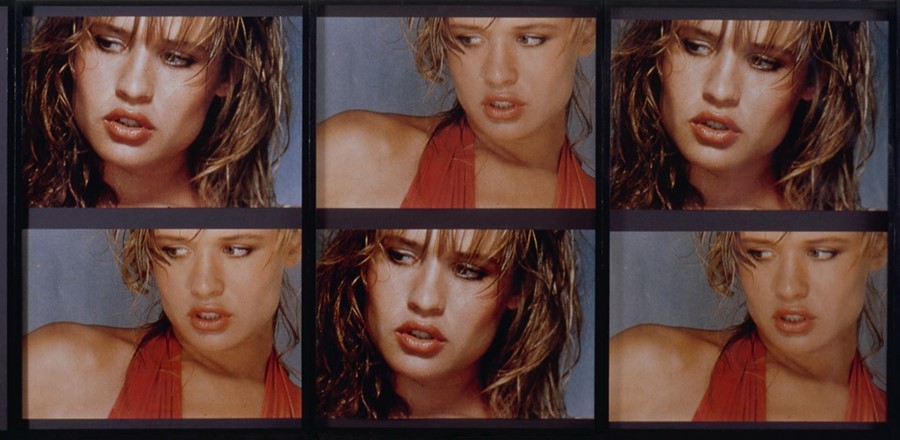

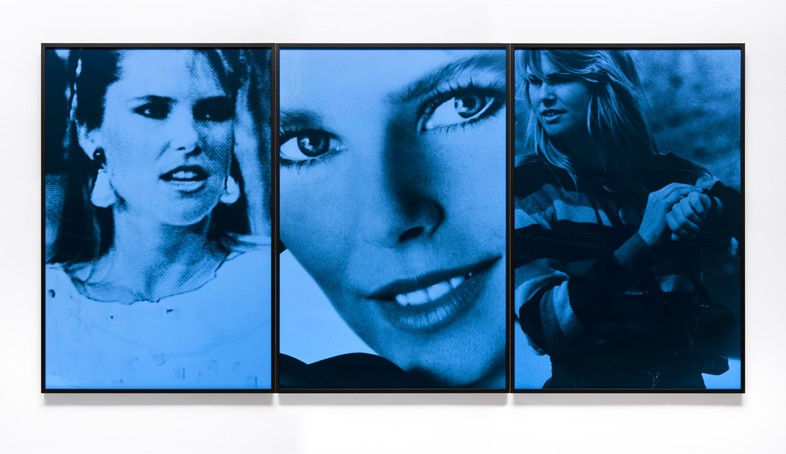

Who? Canadian artist Vikky Alexander came of age artistically in the 1980s New York of Richard Prince, Barbara Kruger, and Sherrie Levine. She was the youngest and least recognised of this famous group, and used conceptual photography to demystify and understand visual codes. Like her more established peers, her strategy was one of visual appropriation, manipulation, and re-contextualisation: she re-photographed and manipulated generic images of female beauty taken from European fashion editorials, then re-presented fashion’s fantastical yet familiar images in a high art context. Where many artists have tried to shatter consumerist fantasies by offering explicitly critical alternatives, Alexander took visions of capitalist escapism— and amplified their effects to the max.

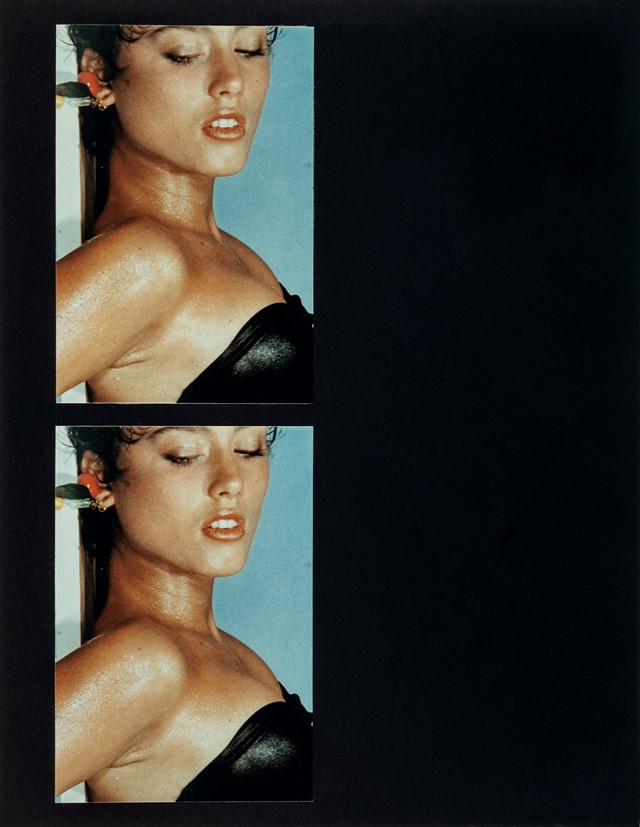

What? Alexander’s work recalls French theorist Roland Barthes’ dictum on the languages of visual culture: “a code cannot be destroyed, only ‘played off.’” By foregrounding the fashion photograph’s role as a vehicle conveying notions of physical acceptability, Alexander encourages viewers to become aware of ideological mechanisms at play. Alexander’s aim when making these works was to “look at myself looking at other women.” She is speaking both literally and metaphorically; her appropriated images are mounted on mirror-like black surfaces, so through a process of visual superimposition, the idealised image and the viewer gazing at it become, in a sense, one. Alexander is interested in the inevitable comparison that ensues from this collaboraion. “I don’t want to speak for all women, but I think many of us have a love/hate relationship with fashion," she states, "You can try, but you will never attain the idealised glamour of an editorial. There’s an ambivalent push-pull effect; one knows the unattainability of media images, but desire can make you blind to reality."

Working in art history-inspired diptych and triptych formats in this series was Alexander’s attempt to “give something fleeting and changeable, fashion, a longer lifespan of relevance.” St Sebastian (1983) alludes to ideas of physical martyrdom, connected to the pursuit of perfection. A swimsuit model, originally photographed lying down, is placed upright as if bound (Sebastian was shot through with arrows while tied to a stake). A masculine religious and historical trope becomes a secular, female, and contemporary narrative. Another work, Pietà (1981), in which a man watches over a reclining female model, reverses the roles of the Virgin Mary mourning the dead Christ in Michelangelo’s iconic sculpture. In this sense, Alexander’s women become less passive objects awaiting visual consumption in the space of an editorial, and more protagonists, existing in a rich historical lineage.

Why? Despite working in the illustrious vein of the Pictures Generation during the eighties, Alexander never gained the level of recognition her peers did. As contemporary visual culture becomes an ever more saturated and frenetic field, however, Alexander’s work of this period only increases in relevance. In an age of endemic photographic re-touching and the flattering filters of Snapchat and Instagram, Alexander’s early work reminds us of the ways technology has increased the demands on female perfection. “Looking at the photographs now I notice that, despite being visions of ideal beauty, there are still blemishes and visible pores,"she reflects. "They’re not retouched to the degree photos are routinely altered now. You can see skin!” By examining the blue-steel stares of the 1980s supermodel, Alexander offers us the opportunity to reassess current culture using the lens of the recent past.

Vikky Alexander: The Temptation of Saint Anthony runs until June 18, 2016 at Cooper Cole Gallery, Toronto.