As a new retrospective prepares to open at Tate Liverpool, we present a concise overview of the controversial British artist's powerful oeuvre

Francis Bacon was born to wealthy English parents in Dublin in 1909, and had a colonial childhood amongst the Troubles in a succession of Irish country houses. It was, however, not a happy one: horse-whipped by his father, distant from his mother and locked in a cupboard by his nanny, he came to understand conflict, danger and confinement from a young age. Finally, at 16 years old, the young artist was caught by his father dressed up in his mother’s clothes, and banished to London with just three pounds a week to live on.

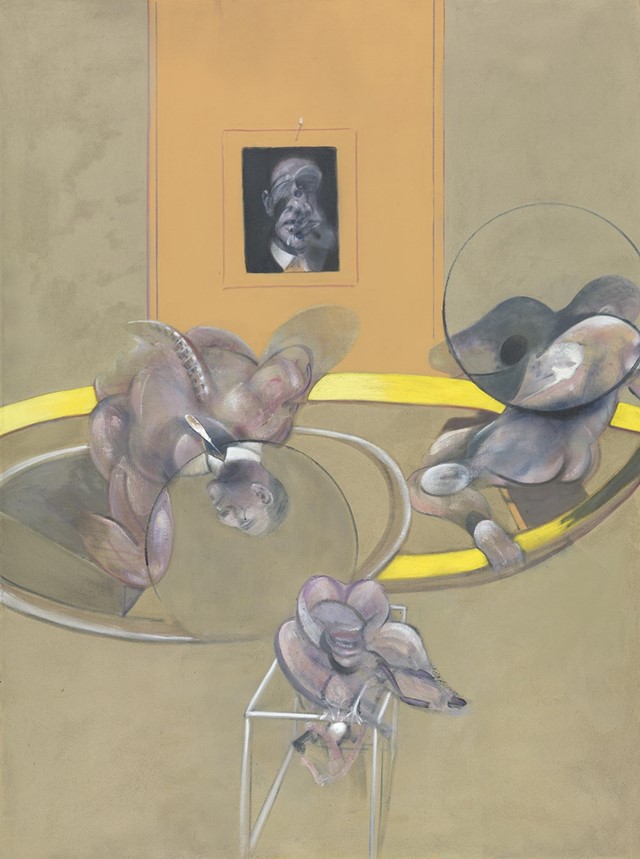

The meagre allowance didn't trouble Bacon overly: he lived on his wits, and the indulgence of older male lovers, enjoying the delights of Weimar Berlin and bohemian Paris before designing Art Deco furniture from his small London studio. Soon, however, Bacon took to painting, and the medium quickly became Bacon’s lifelong obsession. Rejected by the Surrealists, he set about inventing a radical new style of psychological painting, marked by a particular fascination with the mouth and its potential for both pleasure and pain. He depicted harrowing crucifixions, screaming caged figures and nightmarish anthropomorphic creatures in striking furnace reds, masochistic pinks, electrical oranges, nightmarish purples and yellows reminiscent of bodily fluids. His are some of the most arresting images in the history of Western art, and epitomise the raw existentialist style that characterised his work all the way up until his death, on holiday in Madrid in 1992.

1. A Radical Approach

Bacon's famously messy and eclectic studio at 7 Reece Mews in London’s South Kensington (now recreated at the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin) was the epicentre of his world. Heaped piles of rare medical textbooks, snapshots of crime scenes, crumpled Renaissance reproductions and technicolour celebrity photographs became a personal archive, layered with years of paint and dust. Bacon’s confident erudition didn’t distinguish between Old Master paintings and Hollywood stills. He preferred to work from images or memory rather than life itself, and developed a radical painterly technique based on creative accidents.

Bacon was also a lifelong gambler, and enjoyed confronting the risk involved in creativity. Flipping his canvas, he worked on the un-primed side, using not only his brush but his hands and bits of old rags too, to create an aesthetic both of delicate yearning and brutal violence. It was the resonance of a memory or a feeling, its echo filtered through the mind’s eye, which was, for Bacon, worthy of capturing.

2. Soho Socialite

Equally at home in the dining room of the Ritz Hotel as in a dishevelled Soho pub, Bacon was an outrageously heavy drinker, remembered for his "splendid manners" and his generous friendships. When not holed up in his studio, he was often to be found at the heart of Soho’s bohemia. A flamboyant bon vivant and friend of fellow painter Lucian Freud, he was an early patron of the Colony Room in Dean Street, an establishment owned by the formidable Muriel Belcher, who addressed everyone as "C**ty". Propping up the bar most afternoons, Bacon mused on his teenage seduction by the stable boys, and claimed to fancy his father. His social life was much like his working life; an example of what his friend Daniel Farson called "calculated chaos".

3. Mortality and Mutilation: The Bloody Body

It isn’t surprising that an unconventional man like Bacon – witness to world wars, the Holocaust, the Atom Bomb and the Cold War – had a bleak view of humanity. His now iconic figures are animalised and defined by conflict. Their faces are diseased, their mouths gape with rotting teeth, their bodies horrifically mutilated. Bacon’s bodies cannot simply be; they are acted upon and done to. His tortured figure studies of the late 1940s evoke a hypnotic Victorian freak show. The crucifixions are approached with a butcher’s scrutiny. The famous screaming Popes of the 1950s horrify and fascinate in equal measure; they scream in judgement from their electric chairs whilst crying out for mercy and meaning. His 1969 portrait of friend Henrietta Moraes has her pinned to the bed with a syringe puncturing her right arm. Many of his bruised nudes engage in a Baroque contortion of pleasure and pain, a kind of torture porn where violence and sex are often interchangeable. Bacon always maintained that he wanted to produce images of beauty, but that he "would rather have torment than annihilation": where beauty nullifies, torment at least allows for the possibility of change or transformation.

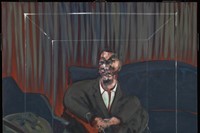

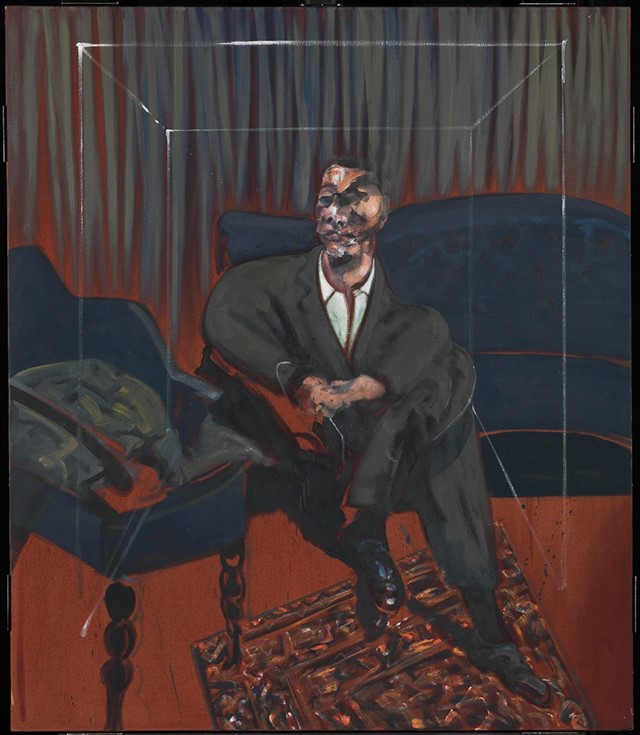

4. The Invisible Box

Bacon saw clearly that his century’s keynote was that of imprisonment. By 1949 his figures, and most notably his iconic screaming Popes, find themselves positioned like scientific specimens within what appears to be a glass box or frame. These Cubist "spaceframes" are a compositional device which deliberately concentrate, clarify and emphasise his subject. The sitter is a caged creature whose potential for horror and violence is contained and distanced and whose desire for succour or deliverance is denied. These spaceframes make Bacon’s compositions instantly recognisable, and it is impossible now not to see these post-war images as a strange prefiguring of Adolf Eichmann, glass-boxed with microphone, on trial for Nazi war crimes in Jerusalem in 1961.

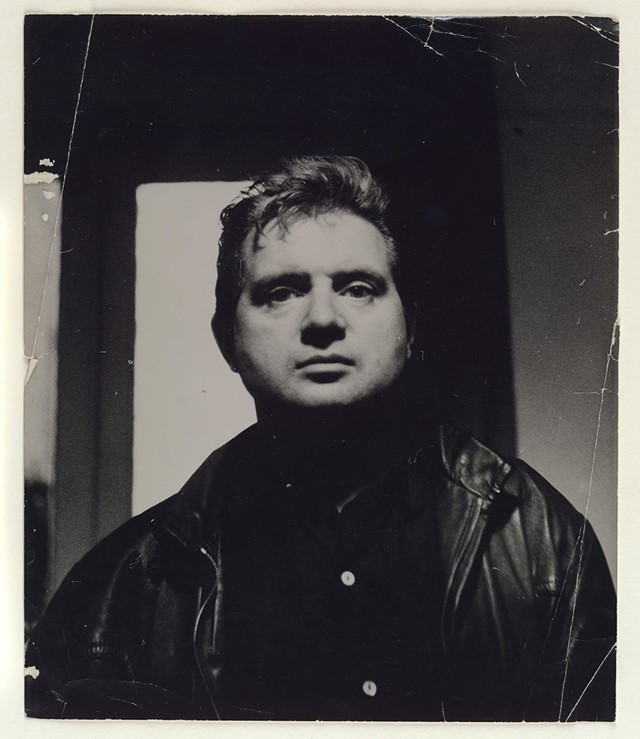

5. Muse and Menace: George Dyer

Arguably Bacon’s most significant relationship was with East End criminal George Dyer. Their first meeting was not a conventionally romantic one – it occurred when Dyer broke into Bacon’s flat in 1964. All the same, the pair enjoyed an intense relationship for nearly seven years, and Dyer quickly became Bacon’s muse. Although disliked by Dyer, Bacon’s brooding portraits of his lover emphasise both a muscular physique and an inner vulnerability.

Dyer was an increasingly insecure alcoholic, and two days before the 1971 opening of Bacon’s retrospective at the Grand Palais in Paris, he committed suicide in their shared hotel room. The trauma of his death led Bacon to produce the haunting Black Triptychs as an attempted form of exorcism. Three triptych altarpieces reimagine the oppressive Paris hotel room, Dyer’s erratic and contorted body and his desperate state of mind. To live fully in the moment, believed Bacon, is to feel death close by – and in this sense George Dyer burned brightly and briefly.

Francis Bacon: Invisible Rooms runs from May 18 until September 18, 2016, at Tate Liverpool.