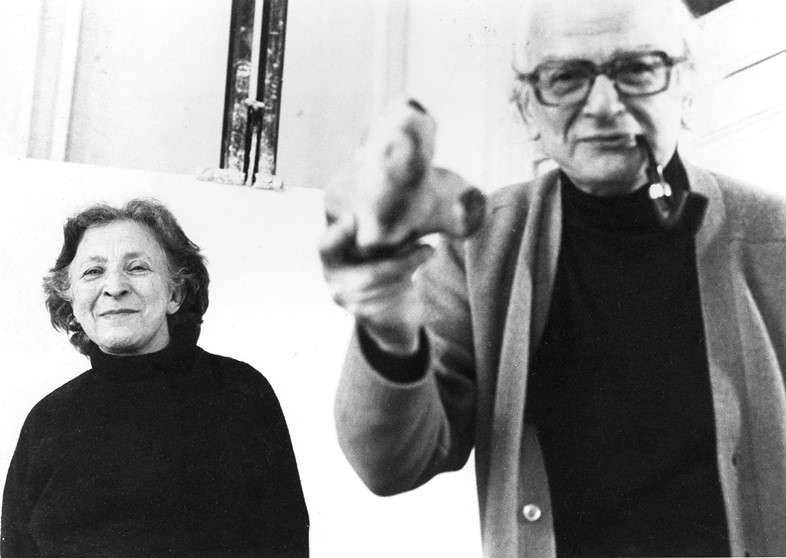

As a new exhibit lifts the lid on the life-long collaboration of Franciszka and Stefan Themerson, we consider their prolific lives and practice, from experimental film to photography and publishing

Who? Partners and life-long collaborators, Franciszka and Stefan Themerson were pioneers of Poland’s pre-war cinematic avant-garde. Never ones to stick to well-established parameters, their practice not only encompassed film but also photography, painting, theatre design, literature, concrete poetry, illustration and publishing. From 1929 to their deaths in 1988, the couple committed themselves to challenging conventions through ceaseless experimentation. With humour and a generous dose of the absurd, they confronted such issues as freedom, ethics, language and the human condition, in films that appeared like moving collages, and literature that defied linear modes of reading. In tune with their Dada and Surrealist contemporaries, their subversive sensibility reflected a deep-set belief in the need to resist man’s conformism, mindlessness and inhumanity. It was, no less, in the grim climate of looming war – with Hitler bordering one side of Poland, and Stalin on the other – that the Themersons emerged as the first Polish artists to produce experimental films.

When their paths first crossed in 1929, Fraciszka Weinles – the daughter of Jewish painter, Jakub Weinles, and pianist, Łucja Kaufman – was studying painting at the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts; Stefan Themerson – the son of a family doctor – was a published poet and writer, who had been flirting with physics before trying his hand at architecture. Having graduated, the couple soon married and, by 1938, the year they emigrated to the unruly hub of the art world – Paris – they had spawned five films, co-founded a film makers’ cooperative and published a film journal, f.a. War soon found them in Paris, and the couple were forced to split from each other, at which point Stefan joined the French resistance while Franciszka relocated to London. In 1940 they reunited in the Big Smoke, eventually setting up Gaberbocchus Press to channel their boundless creativity, from Franciszka’s illustration and book design to Stefan’s poetry, children’s stories and art theory. It became one of the most important post-war avant-garde imprints in the city, publishing titles by a whole slew of history’s most revered artists and writers.

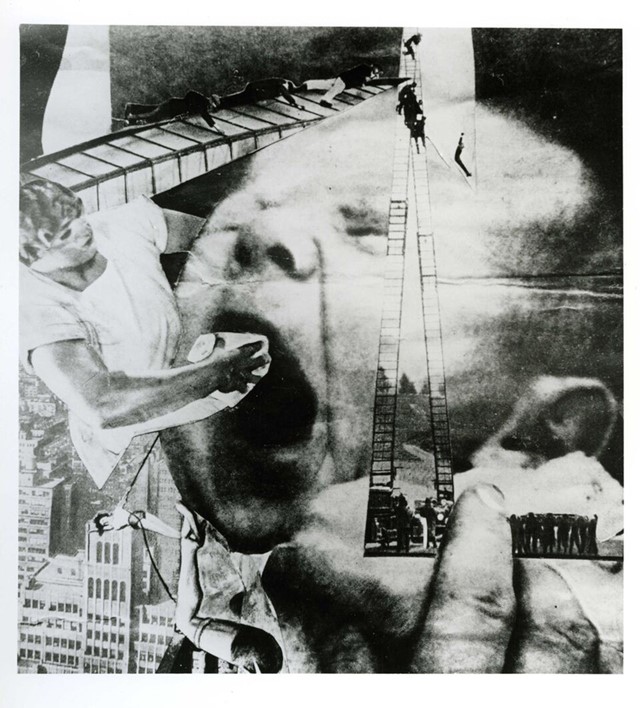

What? Across their entire oeuvre, the Themersons galvanised the iconoclastic spirit of the European avant-garde, with a particular penchant for dismantling the boundaries of the mediums in which they worked. When it came to film, Stefan invented ‘photograms in motion’ – a form of ‘cameraless photography’ that created outlines and shadows on paper, giving the illusion of movement and abstraction when filmed frame by frame. Though their abstract forms nodded to their Constructivist ancestors, it was minus their utopian ideals, dented by the rise of fascism. If anything, their work leaned more towards Dada. One of their most acclaimed films, Europa (1931), engendered surreal juxtapositions through Dada-like collages that escaped the cinematic language of the time. Meanwhile, their only colour film, Calling Mr Smith (1943), spliced fragments of newsreel footage with photograms, book pages and posters that served as a rallying call for the British public to open their eyes to Nazi atrocities. As always, their aesthetic was bound to their politics.

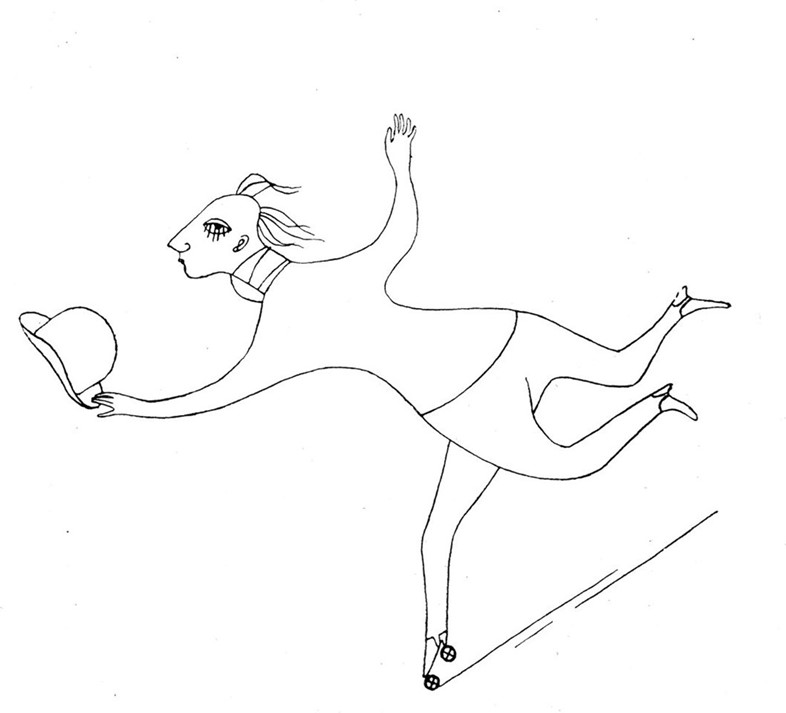

Of course, not everybody welcomed the Themersons’ radical forms of art. Facing rejection, in 1948 the couple co-founded their own press, under which they could champion progressive culture. Gaberbocchus was suitably named after the Latinised version of Lewis Carrol‘s nonsense poem Jabberwocky – a sign of the imprint’s absurdist sensibility. Housed in their Maida Vale flat, it was devoted to books that would be “the best lookers, rather than the best sellers” – in other words, books that were as eye-popping in form as they were in content – favouring innovative combinations of text and image. Beyond Stefan’s own literature, Gaberbocchus valiantly introduced a British audience to texts by such cultural propellers as Alfred Jarry, Kurt Schwitters, and Guillaume Apollinaire. Jarry’s anarchic play Ubu Roi (1896; 1951) was their flagship publication – a monstrous critique of fin de siècle decadence, pillared by savage humour and a ridiculous megalomaniac. Hand-pressed and ingeniously illustrated by Franciszka, the play’s grotesque sense of the absurd had a profound influence on Franciszka, who would go on to design medal-winning sets, costumes and puppets for Ubu’s various re-enactments.

Why? In a day and age when artists typically work across multiple mediums and channels, the oeuvre of Franciszka and Stefan Themerson provides endless inspiration for multi-disciplinary practices. Luckily, anyone in London over the next couple of months will have the chance to glimpse into their prolific lives at the Camden Arts Centre’s exhibition Books, Camera, Ubu. Focussing on the Themersons’ film practice, the Gaberbocchus Press, and Franciszka’s varied responses to Ubu Roi, the exhibition proffers a wide vista of their diverse output. While only the last two of their seven films survive, archive material provides ample visual and textual clues for the radically experimental ways in which these moving images unfurled. What the exhibition will have little trouble in indicating is not simply the innovative approach they assumed throughout all strands of their practice, but also the manner in which they married content and form – politics and aesthetics.

Books, Camera, Ubu is at Camden Arts Centre from March 24 - June 5, 2016.