The signs created to protest against the Vietnam war are now on display in a London exhibition, curated by none other than counter-culture historian Barry Miles

Jack Kerouac; William Burroughs; Paul McCartney; Allen Ginsberg; Charles Bukowski. The list of genre-defining figures – whether poets, artists, writers or musicians – that English author Barry Miles has written about over the years reads like a who’s who of 1960s and 70s counterculture. Perhaps more fascinating, however, is that Miles lived this era first, and wrote about it second – almost all of his literary subjects having been real-life friends and acquaintances first.

Miles himself is something of a cultural icon in these circles. In 1967, he organised the 14-Hour Technicolour Dream, a concert which hosted musicians from Pink Floyd, to Yoko Ono and John Lennon in a bid to raise money for his international newspaper project, International Times, which was also part-funded by Paul McCartney, while two years earlier, his Wikipedia page reports that Miles and his wife had introduced that same quiet investor to hash brownies, using a recipe they found in The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook. In the 1970s, Miles and his wife lived on Allen Ginsberg’s farm with him in rural New York state. The stories he lived, it seems, are equally if not more compelling than those he wrote.

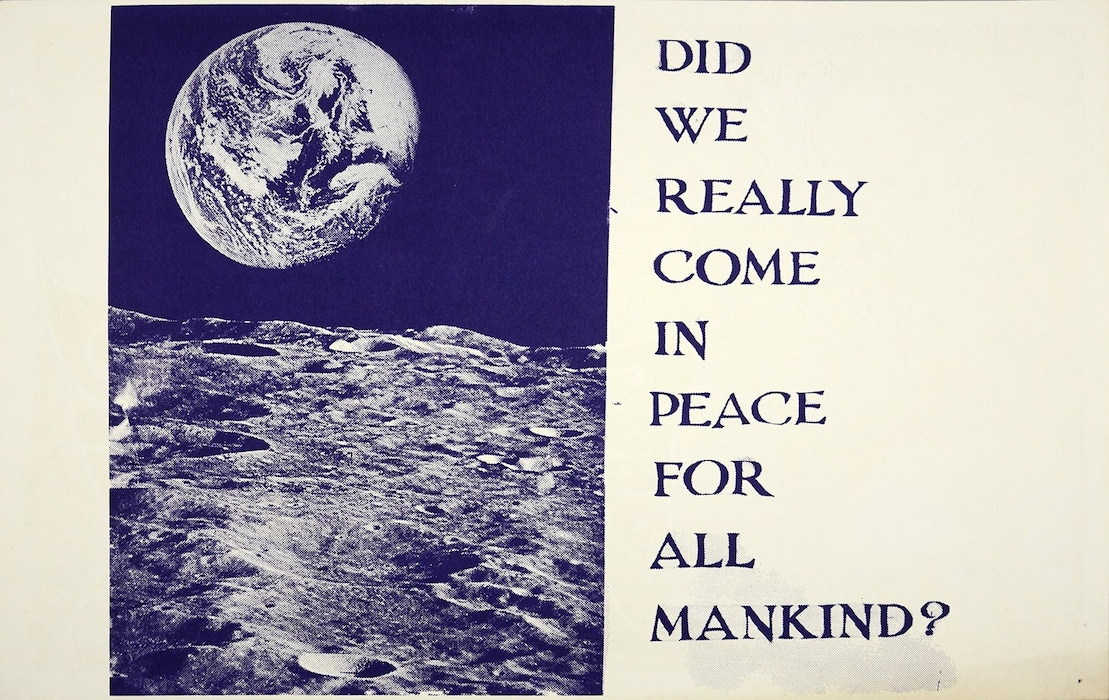

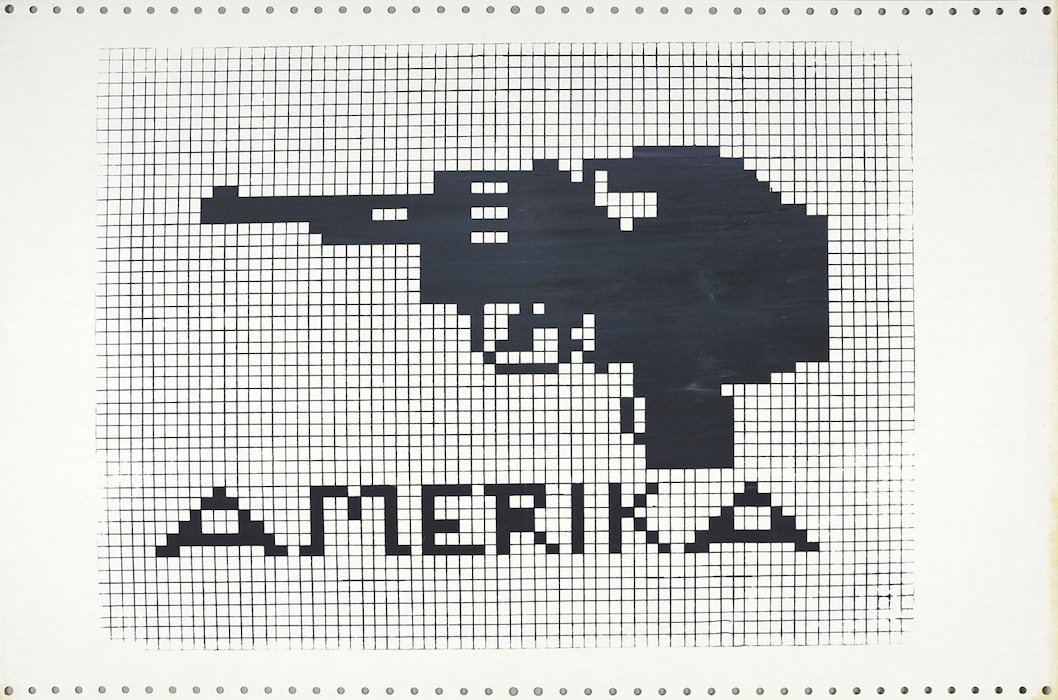

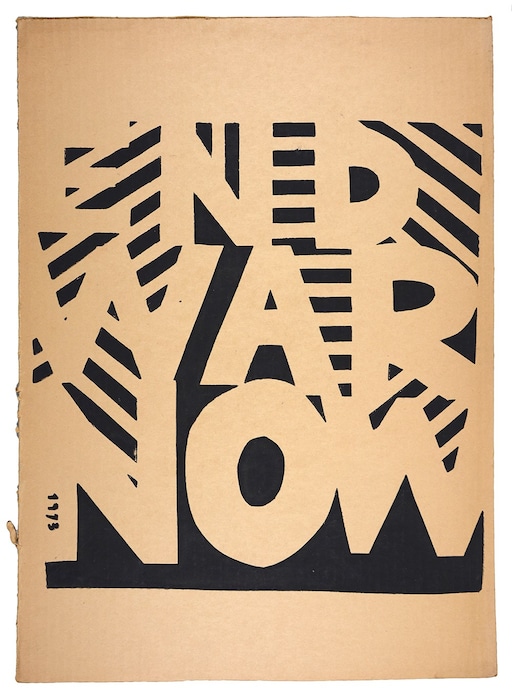

In the early 1970s, Miles was in California, where he saw both the fury against American involvement in the Vietnam War and the growing use of psychedelic drugs firsthand. In 1970, these singular factors collided in a series of demonstrations at Berkeley University, California – and the posters which were created to get the message across are the very objects on show in a new exhibition titled America in Revolt: The Art of Protest, curated by Miles, which opens this month at London gallery Shapero Modern. Here is Miles himself, on the unique combination which caused the riots, and the unexpected beauty of the printed ephemera which emerged from it.

![1.-American-Flag-[Untitled],-1970,-Courtesy-Shaper](https://images-prod.anothermag.com/1102/azure/another-prod/350/1/351795.jpg)

On the posters he selected, and the outrage which caused them to be created in the first place…

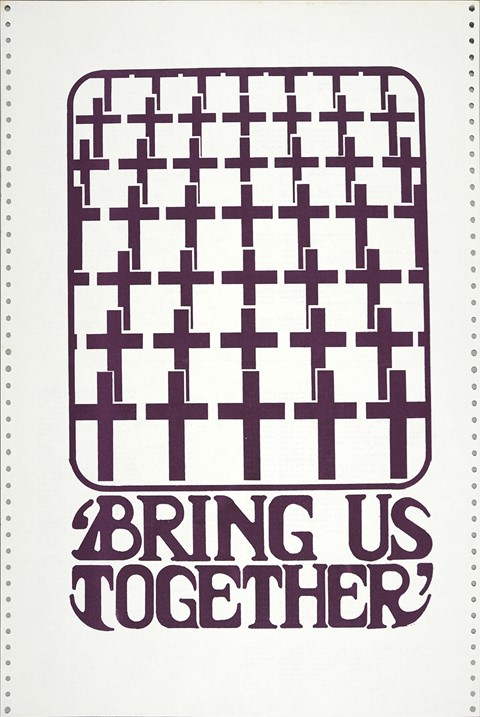

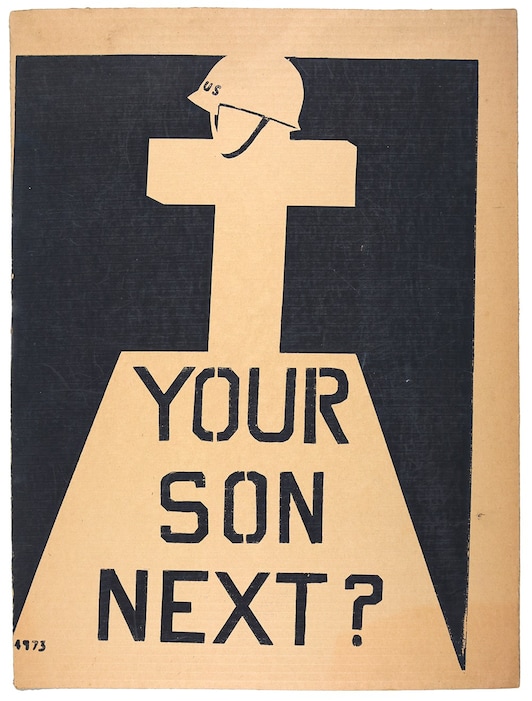

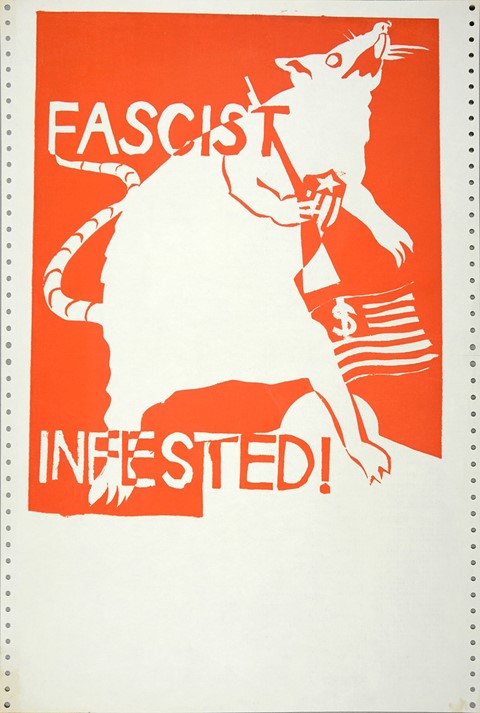

“These posters were made for a series of demonstrations organised in Berkeley initially as a response to the American invasion of Cambodia, then as a protest against the murder of innocent students on a college campus by the National Guard. This was the infamous Kent State massacre, at Kent State University in Ohio when on May 4, 1970, the university authorities called in the National Guard to break up a peaceful student demonstration. 28 National Guardsmen were ordered to open fire on a group of unarmed students, some of whom were on their way to classes. Their 13-second burst of gunfire killed four students, left one permanently paralysed and eight others injured.

All across the country, students reacted with outrage, with major demonstrations, sit-ins and occupations in virtually every major university and college. Ten days later, two students were killed at Jackson State University in Mississippi, one of whom was walking home past the demonstration. Over a dozen students were injured, some of them hit by bullets when police fired 460 rounds into the college dorm. It really seemed as if the authorities hated young people, particularly college students who questioned what was going on in America. These posters were made for these demonstrations.”

On recurring themes in the visual language of protest…

“The peace symbol created by Gerald Holtom for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in January 1958 has been used extensively ever since then, though not very many examples occur in this particular collection. The way the peace symbol was adapted by French artist Jean Jullien to incorporate the Tour Eiffel after the recent terrorist attack in Paris was ingenious. The dove has been used as symbol of peace throughout history, but this meaning was strengthened when the World Peace Congress in Paris in April 1949 chose Picasso’s lithograph La Colombe as its emblem. Other themes include children’s writing and drawing – or child-like writing; flowers, photographs of children, all symbols of innocence and vulnerability in the face of military night.”

On his favourite poster in the exhibition, or the absence thereof…

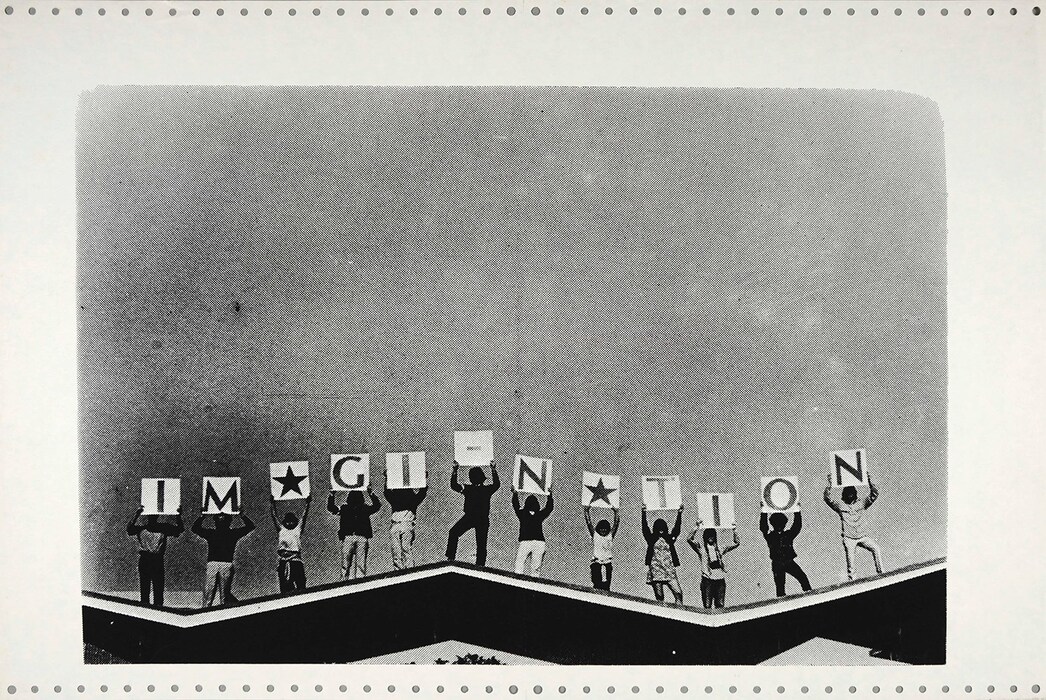

“This is not really the sort of exhibition where you have a favourite. They are political posters, and what I like and admire about them is the sense of urgency that comes across; the need to respond to the situation. They were rapidly silk-screened on the backs of discarded computer-paper, most of which still has its perforated tractor holes on the sides; they have not even been torn off. Even now, more than 40 years later, you can feel the excitement, the anger and the dedication to purpose of the anonymous group of artists who were making them. It is this focus and dedication that I like about them.”

On how he first came into contact with the archive…

“I used to be part owner of ECAL, a poster distribution company, back in the 60s. Among the posters we sold were those published by Oz magazine. It was a typical hippie outfit, terribly disorganised, and Felix Dennis, who worked at Oz, came on board to sort it out. He always had a good head for business, which is why he became one of the 100 richest men in Britain. Felix was very keen on the American psychedelic posters and took a copy of every new one that came in. This was the basis of the collection. Over the years, as he became richer and could afford to buy mint copies and first printings, he accumulated a collection of over 1000 posters, almost all from the 60s, but the core of the collection came from those early days in 1967. I first archived his collection back in the late 70s and did so again when he died on behalf of the Estate. He was a good friend.”

America in Revolt: The Art of Protest runs until February 27, 2016 at London’s Shapero Modern.

![3.-Belloli-[Jay],-Amerika-is-Devouring-Its-Childre](https://images-prod.anothermag.com/483/azure/another-prod/350/1/351797.jpg)