A show at MoMA marks the recalibration of "the world's most famous unknown artist"

Yoko Ono is a complex figure. She is an innovator, part of the Fluxus scene in 1960s downtown New York, a musician, a peace activist, an environmentalist, a mother and a feminist, yet her name is most commonly used as shorthand for “breaking up the band”. Her third husband John Lennon described her as the world’s most famous unknown artist, while the world reviled her as the woman who destroyed the Beatles. She has battled ferocious negative publicity from an international battalion of haters yet wields a social following of 4.7 million Twitter followers and 167k on Instagram.

At 82, she is heading along a path towards total public recalibration. But perhaps it was the years of being considered only as the malevolent “other woman” in the Beatles saga that created the space and freedom for her provocative and exhilarating work. While the storm raged outside, at its eye moved this humorous, revolutionary and quixotic artist, quietly creating pieces that stand today as revolutionary. Indeed, Jonathan Jones asked recently, “Is there any contemporary art style she did not pioneer?”

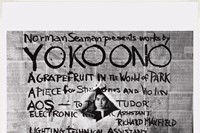

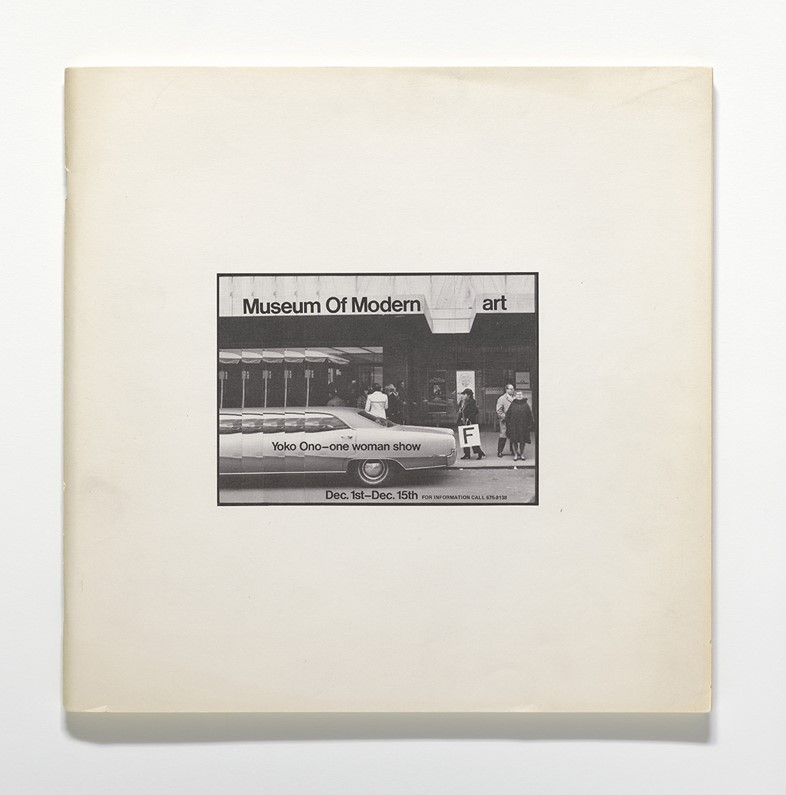

Last month, MoMA opened Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960-71 – at once the first time the museum has dedicated a show exclusively to the artist, and a knowing homage to the unofficial show of the same name that Ono staged there in 1971. Moving through her early work with art scores, via her ground-breaking performance pieces, through the arrival of John Lennon and beyond into their collaborations in art, activism and music, the show is an emphatic assertion of Ono’s relevance to popular culture, regardless of the ever-looming spectre of the Fab Four. Here, we consider three of those pieces and their impact.

Cut Piece (1964)

Cut Piece found Ono kneeling on a stage, a pair of scissors on the ground beside her. An audience was invited to come up one by one and slice off fragments of her clothing, which they could take away with them as mementos. Albert and David Maysles, of Grey Gardens fame, captured a 1965 performance at the Royal Carnegie Hall on film, showing the motionless artist submit her body to the attentions of a series of strangers who, having sliced off their fragment, drop the shears to the floor and head off with their trophy into darkness. As more fragments are cut off, the atmosphere intensifies, the unseen audience begin to snigger and Ono appears more and more vulnerable – finally left with her bra straps flailing, clutching the rags to her body. “I wanted to show the suffering that women go through,” she explained in a recent interview with W Magazine. Cut Piece has been described as “the ultimate distillation of female victimhood, but turned into heroic forbearance” and is widely considered Ono’s masterpiece.

Half-A-Room (1967)

One day in the late sixties, Ono woke up in London to find that her boyfriend Anthony Cox had disappeared from their flat. Her response was a literal one – in reaction to the actual absence of her ‘other half’, she sliced everything – the chairs, the teapot, the pictures, the microwave, the soap holder, the flowers – in two. “Somebody said I should also put half-a-person in the show,” she said. “But we are halves already.” The piece speaks to the pointlessness of material things without the human connection that gives them meaning; the result is a pure, painful representation of heartbreak that takes the breath away.

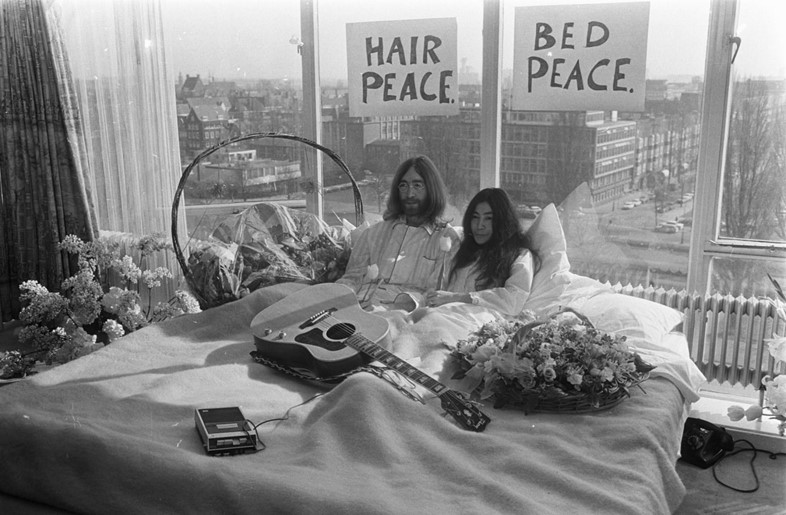

Bed-In (1969)

Following their wedding ceremony in Gibraltar in March 1969, Lennon and Ono travelled to Amsterdam where they set up in the Hilton Hotel to stage their ‘Bed-In For Peace’. They lay in bed, for a week in Holland, and another week in Montreal, inviting the world’s press in to take pictures and ask questions about their opposition to the Vietnam War. Even today it is startling, recalling the power and immediacy of modern social media in the couple's attempt to harness the gaze of the world – intoxicated by fame – and point it in a direction of their choosing. What did it achieve? Nothing definitive perhaps, yet decades on, this work remains revolutionary – it is a headline grabbing act of peaceful protest, it is the most famous people on the planet willingly opening their doors to the press, it is a married couple inviting the world into their honeymoon suite. Most tellingly it is a fusion of the practices of Lennon and Ono, a collaboration that explores the potency of their individual creativity, that resonates far beyond the Vietnam War and the monolith of the Beatles.

Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960-71 is at MoMA until September 7.