We delve inside the complex and enthralling mind of one of the 20th century's most fascinating artists

“Everything I do,” Louise Bourgeois said, “was inspired by my early life.” Born in 1911, the French-American sculptor grew up in Choisy-le-Roi, just outside Paris. At a young age, Bourgeois took on the role of nurse to her mother, who succumbed to Spanish Flu after WWI, and at age 11, Bourgeois witnessed her father’s affair with their live-in English tutor, Sadie Gordon Richmond. These combined events left the artist with life-long psychological scars, memories that forged Bourgeois' unique and disturbing oeuvre of giant spider sculptures and poured-plastic body parts.

A self-revealing, self-lacerating artist, Bourgeois took “fantastic pleasure in breaking everything,” continually probing the themes of loneliness, jealousy, anger, and fear throughout her career. Acknowledging the past as a precondition of her present, the intensely autobiographical artist poured her demons into her work. She subverted female stereotypes, exploring a range of personal themes within the context of feminist concerns, permeating the avant garde with her tenacious spirit and self-reflective practice. Her art was, she believed in a very literal way, her salvation. To mark the show Structures of Existence: The Cells at Munich’s Haus Der Kunst and Prestel’s publication of the same name, we present five things you might not know about Louise Bourgeois.

Bourgeois had a powerful affiliation for animals and insects

Creatures of the natural world were a source of fascination to Bourgeois from the time her father filled the family estate with an assortment of hens, dogs, ducks, rabbits, pigs, and even a donkey. Attempting to decipher her own behavior and relationships, she looked to animals and insects for qualities they might share with humans. “Identification – the power of identification is very strong. I lend the animal, I project the animal and shape my feelings,” she said. Bourgeois’ preoccupation with the spider, a motif in Symbolist art, appears in her work as early as the late 1940s, citied as a stand-in for her mother. “The spider – why the spider? Because my best friend was my mother and she was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat, and as useful as a spider.”

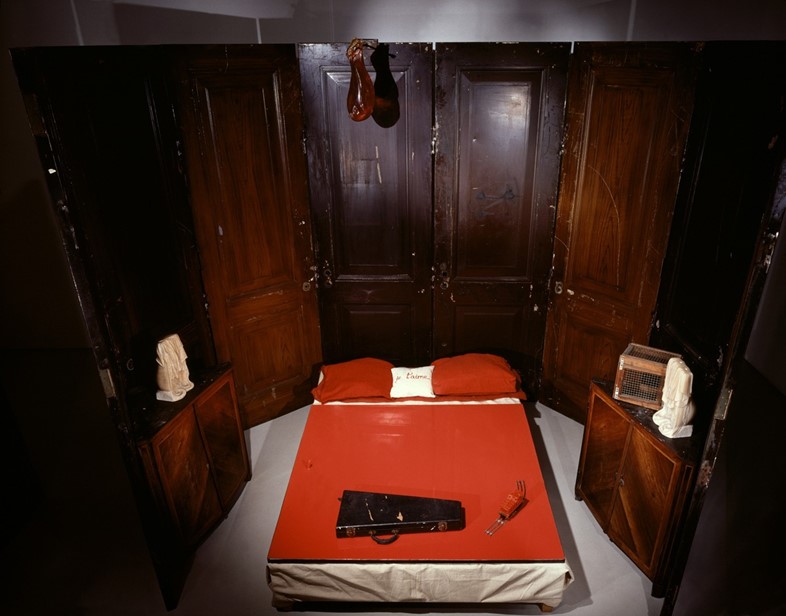

Bourgeois’ experience was her art

Art was Bourgeois’ tool for coping. “I need to make things. The physical interaction with the materials has a curative effect. I need the physical acting out, I need to have these objects in relation to my body.” For her, “art is a guarantee of sanity.” Her works are naked and often anxious reflections of her unconscious. Retrospection and introspection combine in The Cells, a series of small enclosures which represent different types of pain: the physical, the emotional and psychological, and the mental and intellectual. Situations contained within The Cells series are originally of a private and intimate nature. "Every day you have to abandon your past or accept it, and then if you cannot accept it you become a sculptor." For Bourgeois art was “a kind of torment that raged and abated, but could not be cured...In my art, I am the murderer.”

Bourgeois was in psychoanalysis for 30 years

Bourgeois’ childhood traumas relate to her fear of abandonment, stemming from her mother's illness and death, her father’s infidelities and the horrors of the first world war. Believing that she should somehow take her deceased mother’s place in her father’s affections, Bourgeois acted out the classic Freudian dilemma in extremis. In 1951, suffering from depression after her father's death, she entered therapy. Despite profound skepticism, knowing that art was her direct access to the unconscious, Bourgeois craved the self-knowledge that therapy gave her and would undergo analysis up to four times a week. Her doctor’s death in 1982 ended the analysis, and the results are ambiguous. After 30 years of therapy, she never stilled her demons, nor dented her obsessive need to make art. "I am my work,” she declared. “I am not what I am as a person."

Bourgeois ran amazing salons

Bourgeois left Paris for New York in 1938, soon after marrying art historian Robert Goldwater. In 1962, the couple moved to Chelsea, setting up home in a brownstone Chelsea apartment at 347 West 20th Street, which would be her residence for the rest of her life. Beginning in the 1970s, Bourgeois hosted Sunday salons at home where, for the next thirty years, students and young artists would come and talk about their work. Entry was open to all, with Bourgeois’ number publicly listed. “There were only two rules,” said Gorovoy. “You can’t have a cold, and you have to bring your work.” Bourgeois held these salons, which she dryly referred to as "Sunday, bloody Sunday”, on a weekly basis until her death in 2010, at the age of 98. Adapting to her environment with age, in her nineties the artist sat atop a wooden box and a pillow, to raise her high enough for her visitors to see her.

Bourgeois kept an extraordinary journal

Like drawing, writing was a compulsion for Bourgeois. She kept journals throughout her life, believing that “you can stand anything if you write it down… words put in connection and can open up new relations.” The three types of diaries – written, spoken (into a tape recorder), and drawing offer a glimpse into Bourgeois' psychological states. “Diaries mean that I keep my house in order,” she said. Free associations and doodles suggest clues as to the personal relationships and conflicts that inform all her work, and seem to offer direct links to her creative process. In 1992, she wrote, “The work of art is limited to an acting out, not an understanding. If it were understood, the need to do the work would not exist anymore... Art is a guaranty of sanity but not liberation.”

Louise Bourgeois Structures of Existence: The Cells is at Haus der Kunst, Munich until August 2. The accompanying book, by Julienne Lorz is out now, published by Prestel.