As her new exhibition opens in Brussels, we give you a five-point guide to the work of Joan Semmel, whose sex-positive paintings have been gaining overdue recognition in recent years

Joan Semmel is a pioneer of the female gaze, depicting her own and others’ nude bodies revelling in their sexuality since the 1970s. As she has aged, the American artist has continued to paint herself, breaking enduring taboos around eroticism and nudity later in life. Her paintings are soaked in a rich array of colours, with shadows and skin formed from sweeping strokes of blue, purple, yellow and orange. Semmel studied at Cooper Union in the 1950s, marrying at the age of 19 and moving to Spain, where she started a family and practised Abstract Expressionism.

After separating from her husband, she returned to New York in the 70s where she became a prolific painter, exploring the female body through a sex-positive lens years ahead of her time. In recent decades her work has been recognised as part of the growing trend for women-centred painting, and she has been included in solo and group institutional shows at Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (2021–22), ICA Boston (2020–1), and MoMA (2014). Semmel has just opened An Other View at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels with works spanning five decades, her first exhibition in Europe since the 60s.

Below, we give you a five-point guide on Joan Semmel’s pioneering artwork.

1. Joan Semmel began boldly exploring female sexuality in the 1970s

Alongside her contemporaries such as Judy Chicago and Carolee Schneemann, Semmel’s practice challenged the censorship of women’s bodies. In the 70s she began a series of Sex Paintings, which showed nudes entangled in intimate embraces. The works are full of movement and passion, often composed as if the viewer is looking through one of the lover’s eyes. These works highlighted women’s view of sex, celebrating natural urges which to this day are laden with shame and stigma. Her 1972 Erotic Paintings depicted models having sex in the artist’s studio. She struggled to find collectors for these early works, which were deemed shocking in so confidently platforming female pleasure. “Women needed to acknowledge their own sexuality, acknowledge their own desire, and not always deny it, not always be passive,” she told Art in America earlier this year.

2. Her sex-positive approach drew criticism within feminist circles at the time

While Semmel’s work now is often read as intensely feminist, her free depiction of women’s sexuality as something fun and powerful clashed with hardline second-wave views in the 70s. As she told the New York Times, many within the movement assumed “that a woman’s body was colonised territory, that there was no way of using it without objectifying women.” She did not follow this line of thought and was one of the first artists to celebrate the pleasurable potential of women’s bodies in such an honest way. Through a 21st-century lens, her paintings are now seen as empowered and ahead of the curve.

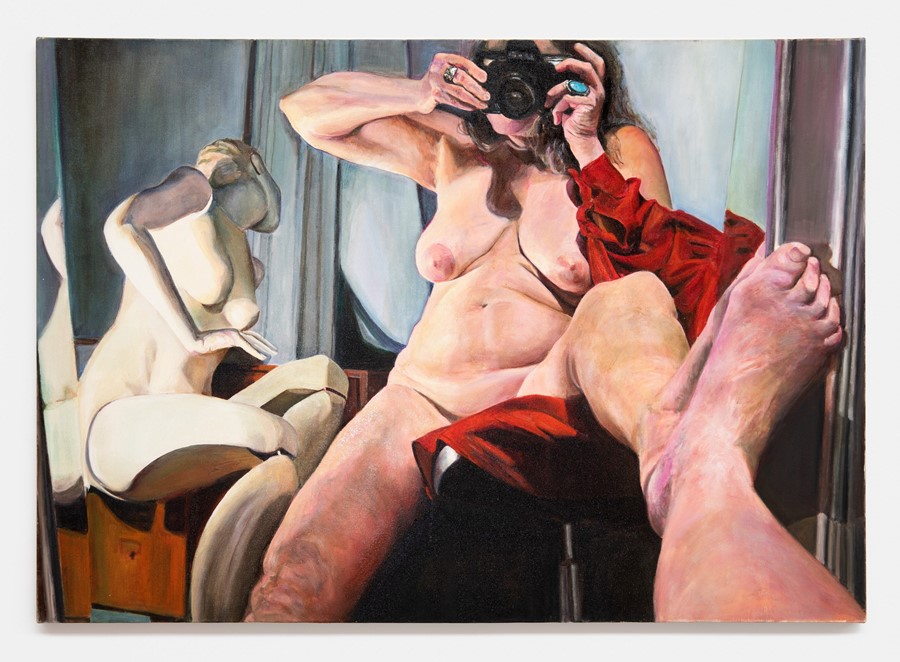

3. She is still one of the only well-known artists to represent ageing sexuality on canvas

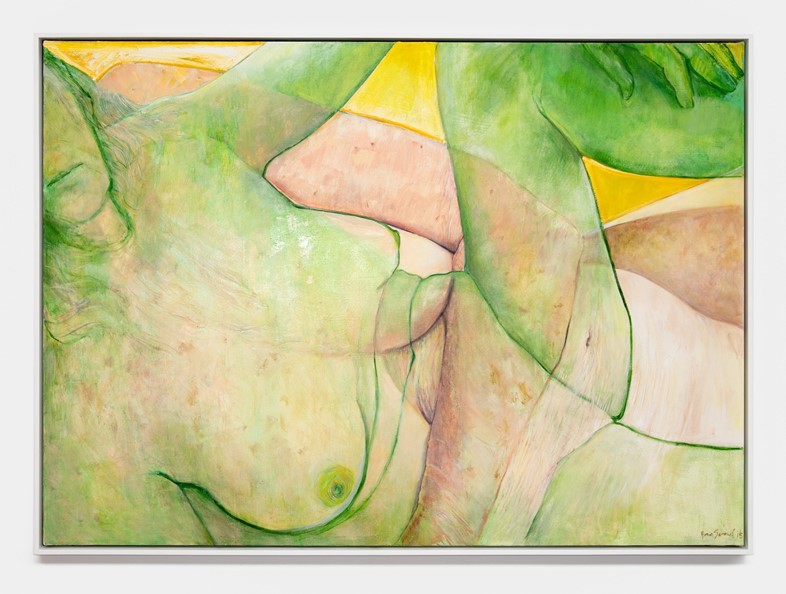

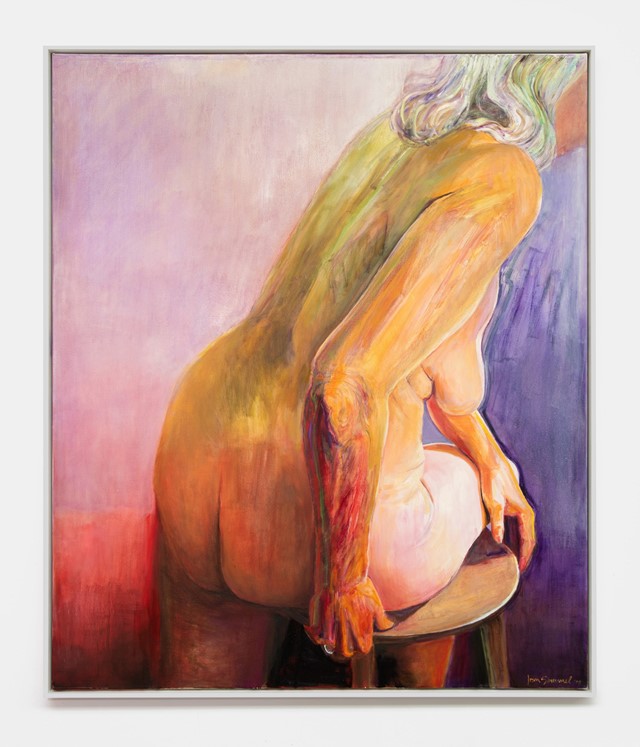

As Semmel has grown older, her works have taken a playful and raw look at sexuality later in life. She often paints her own nude body full of vitality and desire, sometimes in sexual poses, at others in exploratory inquiry as she moves around the studio or photographs herself. Her large turquoise ring can be seen in many of her self-portraits, something she has described as an “identity marker” when her face is not in the frame. Most of these works are painted from her perspective, with giant canvases offering a view down the length of her body, with the shadowed curves of her breasts, arms, hips and legs taking on a landscape-like quality.

4. She trained as an Abstract Expressionist in the 1950s

While painting in Spain at the start of her career, Semmel explored Abstract Expressionism. The movement was dominated by white men and Semmel didn’t wish to be set apart by her gender. However, she began to find this mode of painting too rigid and felt sidelined within it. She embraced figuration and with it her identity as a woman artist. Semmel has said that this was her “way to resist … I decided to say ‘Yes, I am a woman. And yes, I paint like a woman.’” While her works now embrace the naked human body, they contain traces of her Abstract Expressionist past, often formed from kaleidoscopic colours with the body cut up into different planes, where a vibrant blue might meet a soft orange, all evoking the heated fleshiness of the human form.

5. Semmel paints bodies both real and artificial

Skin and flesh are undoubtedly Semmel’s most closely depicted subject, but she has also turned her eye to artificial women’s bodies. After seeing a group of old mannequins discarded on the street, she began a series of works in the late 90s. These depicted the idealised forms of plastic mannequins with an eerie sense of animation, as they gazed at the viewer with sharp gashes across their hips, shoulders and wrist sockets. She found parallels between these fetishised bodies and their careless discarding, writing at the time, “The haunting beautiful faces, broken parts and empty armholes were eloquent witnesses to the way women were valued for their youth and beauty and discarded in later years as powerless and no longer viable.”

An Other View by Joan Semmel is on show at Xavier Hufkens in Brussels until 15 June 2024.