Created by artist-curators Mónica de Miranda, Sónia Vaz Borges and Vânia Gala for the Portuguese Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024, Greenhouse is a symbol of resilience and freedom in the face of colonial empires

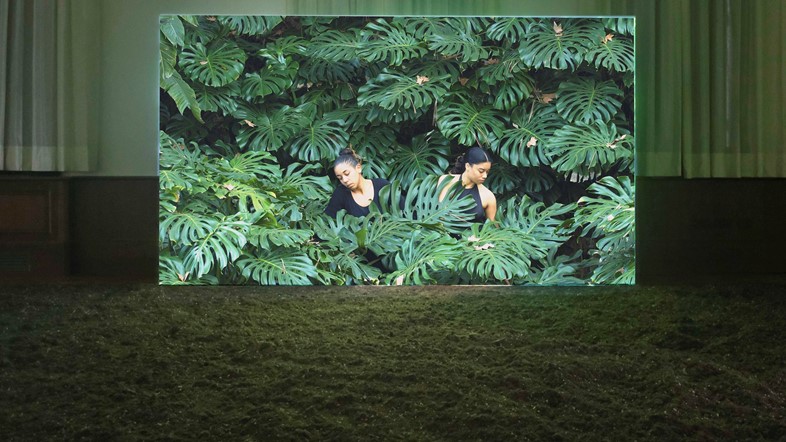

A garden is growing in the elegant interior of Palazzo Franchetti – a particularly opulent Venetian edifice on the city’s Grand Canal. At the top of the building’s palatial marble and stone staircase, with its series of imposing gothic windows overlooking Ponte dell’Accademia, the entire upper floor is lush with vegetation. Each adjoining room is dominated by garden beds hosting a diverse range of plants, herbs, and flowers from lemon trees to monstera, strelitziaceae and pineapple plants. In contrast to the ornate and perfectly symmetrical pattern of flora and fauna painted on the building’s baroque vaulted ceiling above the central staircase, the real plants and flowers growing on the top floor of the palace are not there simply to decorate the space – they are claiming space.

The unexpected garden is an installation called Greenhouse, created by artist-curators Mónica de Miranda, Sónia Vaz Borges and Vânia Gala for the Portuguese Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale. Responding to the international art exhibition’s 2024 theme “foreigners everywhere”, the trio have recreated a Creole garden which, historically, was a plot given to and cultivated by enslaved people in order to sustain themselves. As such, it became an ingeniously diverse model of gardening, planted to provide not only enchantment, but fruits, vegetables, medicinal plants, spices and herbs.

“Creole gardens challenged systems of forced labour and monocultural plantations in colonial empires,” explains artist, researcher, curator and artistic director, De Miranda. “By opting for alternative forms of cultivation such as permaculture and favouring multiplicity, these plantations contributed not only to food and medicine, but also to fostering a sense of belonging and identity. By cultivating the land according to their own traditions and needs, these people were claiming a space of autonomy. The gardens were therefore not just spaces for cultivation, but a symbol of resistance and resilience, a place where people could claim their own dignity and freedom.”

Greenhouse highlights the histories overlooked by dominant Portuguese perspectives, bringing to light Afro-diasporic experiences and challenging notions of identity and nation while addressing the constructed binaries between nature and culture. “It’s a polyphonic assemblage. There are multiple rhythms happening in the Creole garden … plants flourish at different times and, working side by side in collaborative ways, they make new worlds,” says Gala, a choreographer and researcher. “I understand it as a Black practice … also as a counter-plantation technique which, as a system, was a monoculture. It was extractive, it used exploited labour and didn’t allow for that multiplicity of voices. [Whereas, the Creole garden] is a practice of tenderness of caring, of listening to the different plants flourishing.”

The sense of an ecosystem created with the guiding principles of mutuality and symbiosis is reflected in the ways the three artists contribute to the artwork, each bringing their own unique practices into the space. Over the course of the biennale, the garden will function as a “transdisciplinary living archive”, hosting discussions, performances, sound and film installations and more, all feeding into a wider understanding of everything the Creole garden stands for. “This invites another kind of world-making,” adds Gala, “and also invites people to participate in that act, which I think is quite important.”

The Venice Biennale itself is of course an established ecosystem, and the very presence of a Creole garden as a “fugitive practice” is, if not contentious, at least a challenge to Venice’s history of wealth built on global trade and of the systemic prejudice and elitism of the Western art world. “This is a pavilion – it’s not in the Arsenale or the Giardini – but even even so, [palazzos] share a lot of things with the Venice Biennale pavilions in the way that they were created as Western monuments of grandiosity which celebrated monoculture in all ways that we can think about,” says Gala. “Also, the pavilions are based on the idea of a single origin in terms of nation and what we are thinking about with the creation of the garden is a completely different world.”

The artists plan to invite local communities to engage and spend time in the garden. “We will bring schools, elderly people, refugees and migrant communities to create another kind of dialogue – one that is not top-down, but a more horizontal and base-level conversation,” interdisciplinary historian Vaz Borges says. “And it’s through the invitations and our research of other populations in Venice [whom] we can invite to the pavilion to be in conversation with the collective. That’s our goal for the society that we live in and we hope to reproduce this in the garden – our vision of another future; another future that is not just concerned with the human being but with everything and the whole ecosystem we live in.”

Greenhouse by Mónica de Miranda, Sónia Vaz Borges and Vânia Gala is on show at the Venice Biennale until 24 November 2024. The Official Portuguese Representation at the 60th International Art Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia is commissioned by the Directorate-General for the Arts (DGARTES).