Speaking from his new gallery space in Holland Park, Michael Hoppen talks about showcasing the extremes, eclecticism, and many nuances of Japanese aesthetics

Upon buying his first vintage photograph in Portobello Road in the 1980s, Michael Hoppen entered into a love affair with Japan. He had caught sight of a 19th-century albumen print of two Sumo wrestlers, their bodies entwined as they stared back unwaveringly at the camera. Drawn to the strange artifice of the image, for the next few decades, Hoppen began regularly visiting Japan. Still to this day, the gallerist travels at least twice a year to forage for new discoveries.

As an artist-in-training in the 1980s, Hoppen says he was “completely blown away by Japan’s energy and diversity. I was seduced by almost everything I laid eyes on.” Okashi, an exhibition at his eponymously named, newly opened gallery in Holland Park, is a visual testament to Hoppen’s lifelong Japanophilia.

First conceived years ago, Okashi was postponed due to the pandemic. “We knew we wanted to bring many different strands of Japanese culture to light, assembling different works from across mediums into one exhibition space,” Hoppen says. “The common thread running through the show is storytelling, which stems from the traditions of manga that have been prominent for many centuries. These play out in items of clothing, such as the kimono or even a fireman’s jacket that is on display in the exhibition.”

Eclectic and expansive, Hoppen didn’t want to simply repeat or encourage familiar understandings of Japanese art with Okashi. “The show intends to convey narrative and folklore as a central aspect of Japanese culture,” he says. “But the aim was to appreciate that every item on display was handmade with care and fabricated with incredible attention to detail.”

‘Okashi’, which literally translates as sweets or confectionery, also signifies a kind of cornucopia, Hoppen explains. “The concept of okashi used throughout Japanese aesthetic history refers to those things which delight for their strangeness, their humour, or their power to intrigue,” he says. The contrasts conveyed by the word itself mirror the rich complexity of Japanese culture, alluding to juxtapositions between history and modernity, tradition and novelty, innocence to sexually charged imagery, and staged artifice to the realness of post-war street photography.

The striking contrasts at play reflect a country grappling with a new sense of self amid a violent and turbulent history, especially before and after the Second World War, which irreversibly changed the economic and cultural landscape. “Trauma deeply impacted Japan after the war – it brought about a massive rupture in society,” explains Hoppen. “When the Americans occupied Japan, it brought about some fundamental changes. Some aspects of American culture were accepted, but there was always a strong desire to protect and preserve what is considered authentically ‘Japanese’. The culture has been vehemently opposed to forms of intrusion.”

In the post-war era, a school of experimental photographers looking to break convention including Shomei Tomatsu, Daido Moriyama, Eikoh Hosoe, Masahisa Fukase and Nobuyoshi Araki proposed an entirely novel visual language and expanded the very parameters of what photography could be. “Moriyama and other photographers of his generation were creating images specifically for photo books,” says Hoppen. “Photobooks are rare, collectible items that require visual fluency and can initially be challenging for an English person to understand. It can be hard to figure out what you’re looking at, but the more you see, the more you learn.”

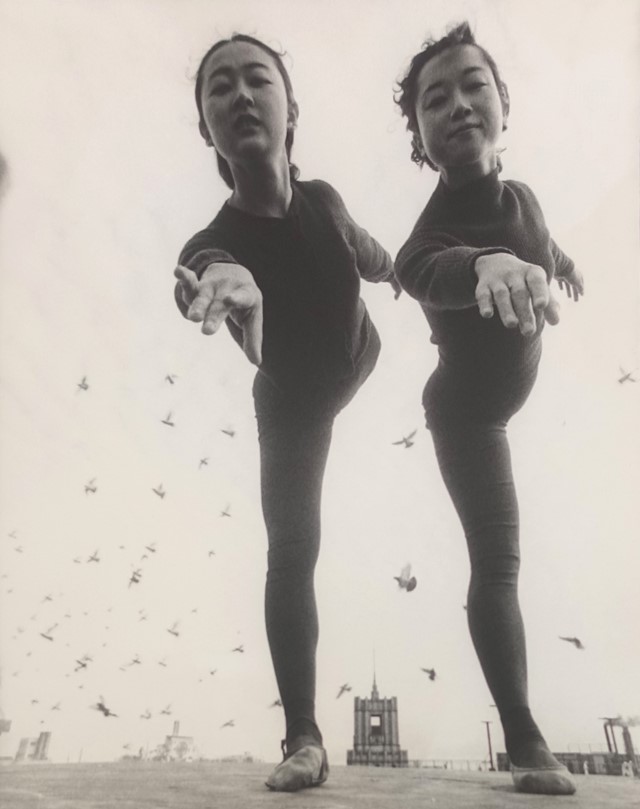

Okashi also assembles the photographic works of Gen Ōtsuka, notably his work Ballet Dancers, Tokyo (1954), which reveals two young dancers leaning down towards the camera in elegant arabesque – a positioning of bodies echoing the staged theatricalism of the sumo wrestlers that had initially attracted Hoppen.

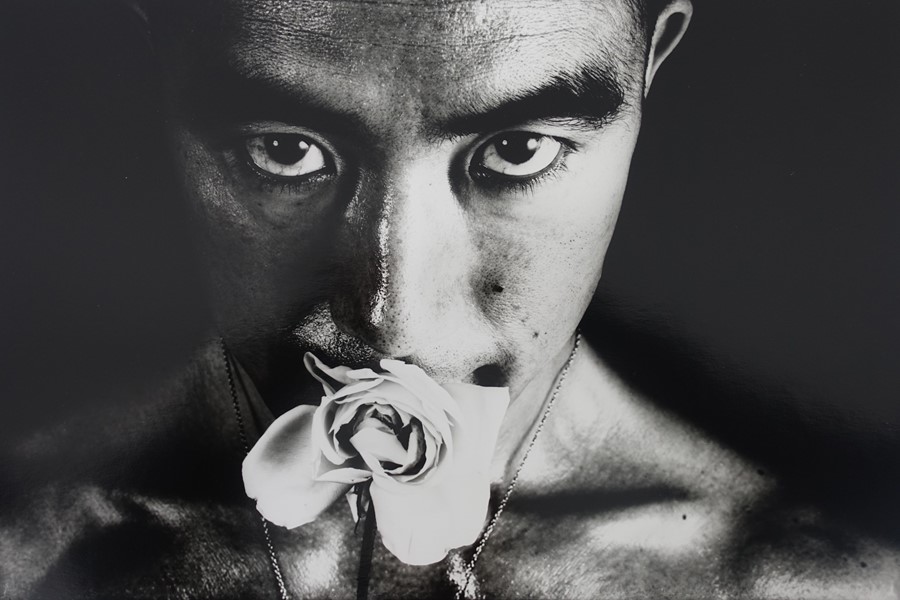

Meanwhile, work by celebrated photographer Eikoh Hosoe is also on display. Hosoe’s iconic series of photographs Barakei, also known as Ordeal by Roses (1961) features portraits of Mishima Yukio – the last samurai to die by ritual suicide (known as seppuku) in 1970. A dramatic moment that shocked the world, the book reflects how Mishima wanted to be perceived after his death – acting as a kind of visual requiem.

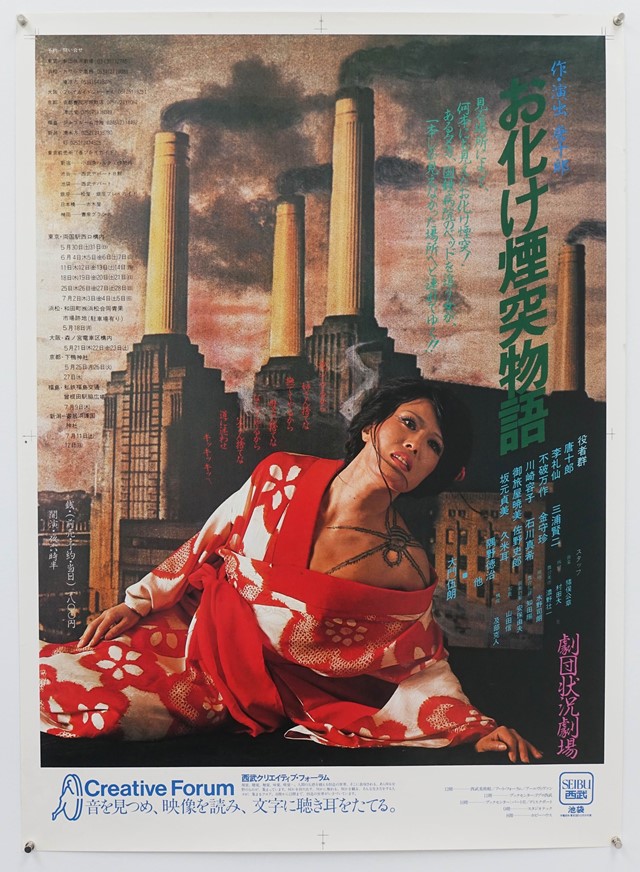

Elsewhere in the gallery, Okashi features work by the prolific photographer Nobuyoshi Araki, whose provocative shots – situated somewhere between fine art and pornography – introduced Japanese audiences to the world of graphic eroticism, continuing the sexually explicit genre of Shunga that had flourished in the 17th-century Edo period but had only been viewed by the elite, ruling classes. “Araki is a figure who is better known outside of Japan largely because he was a very good self-publicist,” Hoppen says. “He’s by no means more or less important than the others, but he was brought up in the heart of the underbelly of Tokyo and was surrounded by the nightlife, the prostitutes, the gangs and the yakuza.”

From a generation of photographers with an open, if not unfiltered, punk spirit, according to Hoppen, Araki was “very fixated on representing Japanese culture in its rawest sense. His work is often misunderstood, but his sexually explicit images and rope bondage works can also be read as reflections of the culture at that time. He’s a kind of diarist who challenged social mores, especially by confronting the increased censorship in Japan in the mid-80s.”

Okashi is an exhibition embracing extremes, eclecticism, and the many nuances of Japanese aesthetics. Reflecting a country that has continually sought to reinvent itself while also resisting influences from the outside world to preserve its culture, the show reveals a kaleidoscopic perspective – a rich visual alchemy of traditions and innovations that shape the delightful strangeness, or ‘okashi’ we associate with Japan.

Okashi is on show at Michael Hoppen in London from 13 April – 30 June 2024.