Philippa Snow’s new book, titled Trophy Lives (a homophonic riff on ‘trophy wife’, the notorious sculpture by Maurizio Cattelan of supermodel Stephanie Seymour), pursues two interconnected lines of thought: “that of celebrities as the subjects of fine art, and that of celebrities as artists – or as artworks – in their own right.” Thus follows a cultural analysis of contemporary image-making, and the various forces – from TMZ’s off-guard paps to art-directed social media content and celebrity plastic surgeons – that have shifted how we look at celebrity, how celebrities control how we look at them, and what this reveals of us and our libidinous desires.

Reviving the concerns of the archetypal art critic – think Leo Tolstoy and Walter Benjamin on the nature of beauty, truth, time, perception, death – through to the hot-babe performances of Paris Hilton, Marina Abramović, Lindsay Lohan, Amalia Ulman, Marilyn Monroe and more, Snow knits together high-brow and low-brow with unrivalled ease. Snow’s first book Which As You Know Means Violence (2022), engaged such methods to analyse self-injury in and as art, pulling together performance artists and pranksters, and the sadomasochistic and the slapstick to revelatory effect. These are themes Snow has been exploring over a decade of cultural criticism: writing for ArtReview, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The New Republic, The Financial Times, and in her very own Screen Shots fiction column for AnOthermag.com (I encourage you to read her short story based on Gus Van Sant’s 1995 black comedy To Die For immediately after this – the themes are apt).

But back to Trophy Lives – here Snow’s thought experiments have something of a magician pulling a rabbit out of a hat; an expertly honed routine, with spontaneous and unexpected digressions later revealing themselves fundamental to the narrative trajectory. Trophy Lives is a masterclass in the essay. It is also intoxicating, shameless fun.

Below, Philippa Snow talks about the thinking behind Trophy Lives.

Isabelle Bucklow: Early in the book, you point to two interrelated threads that the essay will follow: “that of celebrities as the subjects of fine art, and that of celebrities as artists – or as artworks – in their own right”. You’ve long been writing on celebrity, but when did these two categories start to take form?

Philippa Snow: Well, I’ve been writing about art for a long time, too – I fell into art criticism after graduating from art school because I knew I wanted to write, and it felt like a good way to make use of my dumbly expensive degree once I’d realised that I wasn’t also going to be an artist. There are subjects here, like Paris Hilton as a performance artist or the idea of plastic surgery as a medium, that I’ve circled before in my work. The earliest piece I wrote about Paris in that context was in 2013. The structure here is really to ease the reader into the more outlandish suggestion I’m making in the second thread: if I can remind you of the role that celebrities have played in fine art in a more literal way, I’m hoping you’re then primed to agree with me on something nuttier in the back end of the essay.

IB: I love this idea of Paris Hilton not as stagnant but iconic. Hilton’s fixed 00s aesthetic is a very different strategy to Kim Kardashian’s vertiginous metamorphosis. What quality tips something or someone into iconicity as opposed to becoming dated?

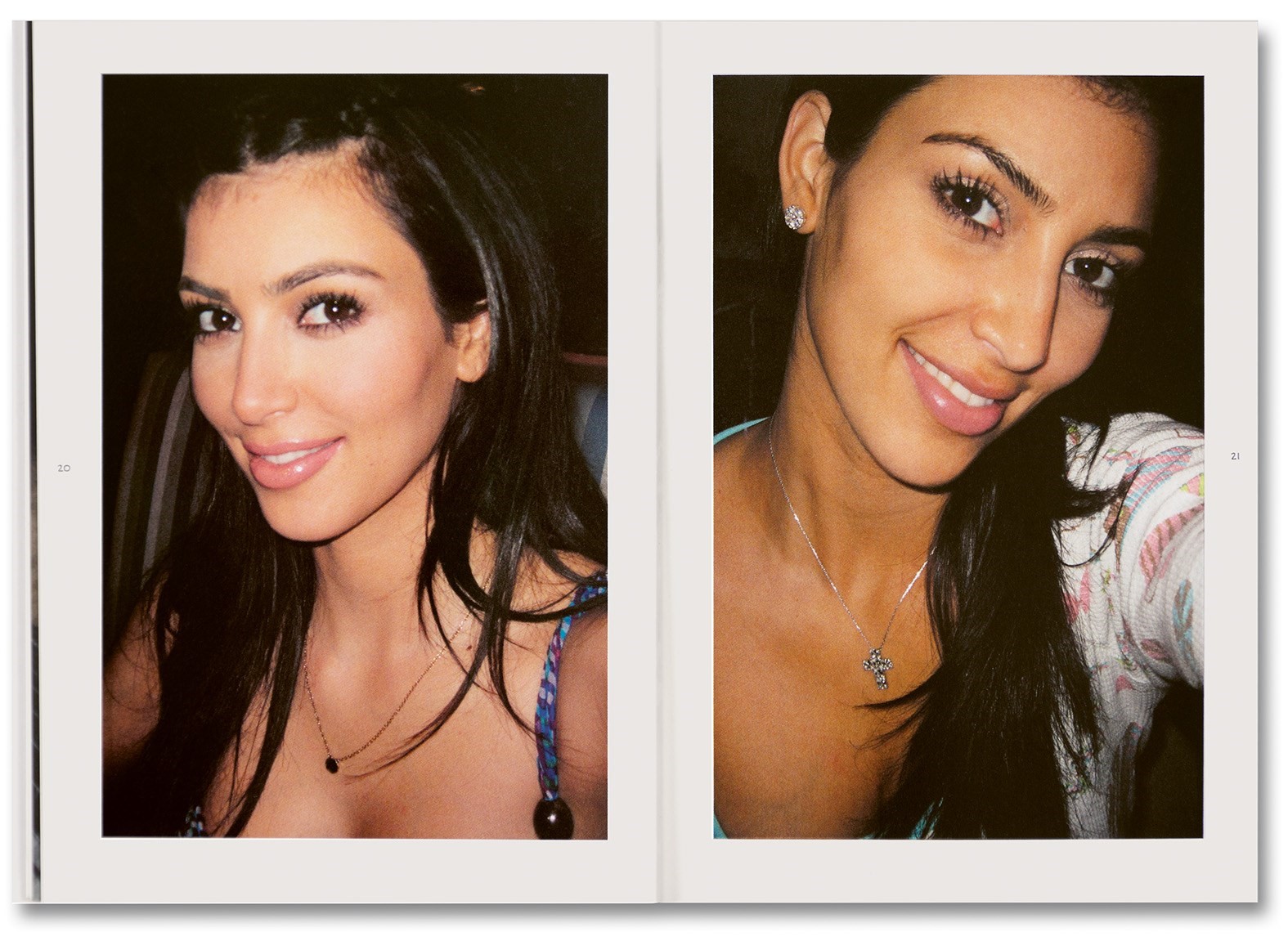

PS: Paris Hilton has, in a sense, benefitted from the cycle of trends that happens with clothes, where what was fashionable 20 years ago comes back into style again. I guess there’s something quite – get ready to take a shot if you are playing a drinking game about the words I’m going to use in this interview – camp about her, isn’t there? Or perhaps I mean kitsch, which isn’t exactly the same. There’s a Milan Kundera quote about kitsch I’ve come back to quite often where he defines it as “the absolute denial of shit.” I think Paris denies her shit in a way that Kim Kardashian – who is happier to talk about her psoriasis or her fertility struggles – perhaps doesn’t. Kim’s job is to be a beautiful everywoman, but Paris’ job is to be Paris. Every public appearance she makes is like rubber-stamping a logo on something. Aesthetically she’s so close to that Warholian idea of being plastic, by which I mean not “like a person with plastic surgery” but “like something that does not really change or degrade in a recognisably organic way.”

“The arc of becoming a celebrity, with all the alterations to the self it tends to require, can look kind of like a horror story from the right angle” – Philippa Snow

IB: Your discussion of doubles compares an eerie Gregor Schneider installation to Kim K’s recreation of her old family home – one of many instances where Kim has amplified a project to such extremes that it’s uncanny and frankly unhinged. There’s a fine line between exactitude and exaggeration here. What happens when that line is overstepped or stretched?

PS: Well, I think too much money can make people a little mad. It can really move the dial on your definition of normality. It’s the extremity of some celebrities’ physical transformations that’s one of the most interesting things to me, really, which is an obvious form of this overstepping into the uncanny valley. Lately I’ve been thinking that reading JG Ballard’s The Atrocity Exhibition as a teenager, with its comingling of celebrity and violence, set me off on a very specific course with my writing. Crash, too. And David Cronenberg’s films, also. The arc of becoming a celebrity, with all the alterations to the self it tends to require, can look kind of like a horror story from the right angle. And when a body is adapted in these very dramatic ways, it almost transcends considerations of attractiveness, and moves into something more like performance. Shaping yourself for an image rather than for real life – what could be more avant-garde than that?

IB: There are few instances where you engage with male celebrities. Elizabeth Peyton’s unflinching and critical portraits of Leonardo DiCaprio do something different to the other case studies in the book. Could you speak to this inversion of the pervasive gender dynamic of male artist/female celebrity?

PS: Those Peyton portraits are such a wonderful opportunity to see an artist’s position on a subject change as both of them mature. I quote Peyton talking about Leonardo’s performance in the film Celebrity in the book, and I really enjoyed that she is kind of rhapsodic about his beauty and his star power – things you’d think a female artist might be penalised for demonstrating an interest in. That painting is all about beauty, and it’s all about desire. When you contrast it with the later piece, Leonardo, you can see she’s not holding him at a remove any more, and part of that is literally because he’s sitting for it, but part of it is that he isn’t an angelic twink anymore. In the first portrait, we’re getting the opportunity to see what a woman sees when she sees a young male celebrity; in the second, we’re getting to see what a woman sees when she sees a middle-aged man. I don’t think that second work is critical – it’s honest. There’s a respect there that comes from an acknowledgement of his personhood rather than his perfection.

IB: You write from a step removed, first desiring Leo and then interrogating the mechanics that set that desire up (while remaining affectionate rather than dismissive of celebrity). From what position is the critic best placed to address celebrity meaningfully? What other critics do you admire for this?

PS: My attitude to these people is that I’m interested in finding out what they tell us about ourselves, rather than necessarily passing a moral judgement on the fact that they exist at all. In terms of a writer covering celebrity, I think Hilton Als has produced some of the most remarkable work on the subject that I can think of. When he writes about Michael Jackson or Prince, he does so with this completely invested, totally unapologetic intensity, and he also writes in an almost novelistic style, all gorgeous prose and doglegs and delicately articulated imagery. Engaging with this stuff seriously with as much skill as Als does makes it serious. He tells you why it matters, and he tells you so fucking beautifully that you have to agree with him.

IB: You have a brilliant knack for making entirely unexpected connections, pulling a Joan Didion quote out of context to describe Kim K. It’s such a Philippa Snow move, both tongue in cheek and profoundly revelatory. Do you think of this technique as a game, a methodology?

PS: I’ve been caught out! In fact, I do see making those kinds of connections as a game, although a bit of it is that I do it because it brings me pleasure. With something like that, I think, or hope, that it’s funny, but funny in a faintly absurd way that trips the reader up – it has to walk a line. I feel like if people think I’m merely being ‘pretentious’ in engaging seriously with the kind of subjects I’m sometimes writing criticism about, they’ll tune out, and I won’t reach them. If I can make a throwaway comparison that lands, and that also lets them know that I know that what I’m doing is kind of insane, it keeps them onside. I fear this is going to be like when we found out the Olsen twins said “prune” when they had their photo taken, and it spoiled the illusion too much: people will read my writing and metaphorically see me saying “prune” all over the place. Ah well – I’ll have to find a new trick for the next book.

Trophy Lives: On the Celebrity as an Art Object by Philippa Snow is published by Mack, and is out now.