Ahead of her participation in the Venice Biennale, we explore the rise of one of South Africa’s most innovative artists (and a favourite of Hans Ulrich Obrist)

In late February, on the opening day of the Frieze Los Angeles art fair, a group of journalists huddled around the BMW i5 Flow NOSTOKANA, a seemingly monochromatic silvery-white sedan, parked in a small, elegantly curated space just outside the fair’s entrance. Within just a few minutes, however, the sleek car would burst into life, its exterior (and hubcaps) dancing with colourful geometric patterns, eliciting a ripple of childish excitement from its onlookers.

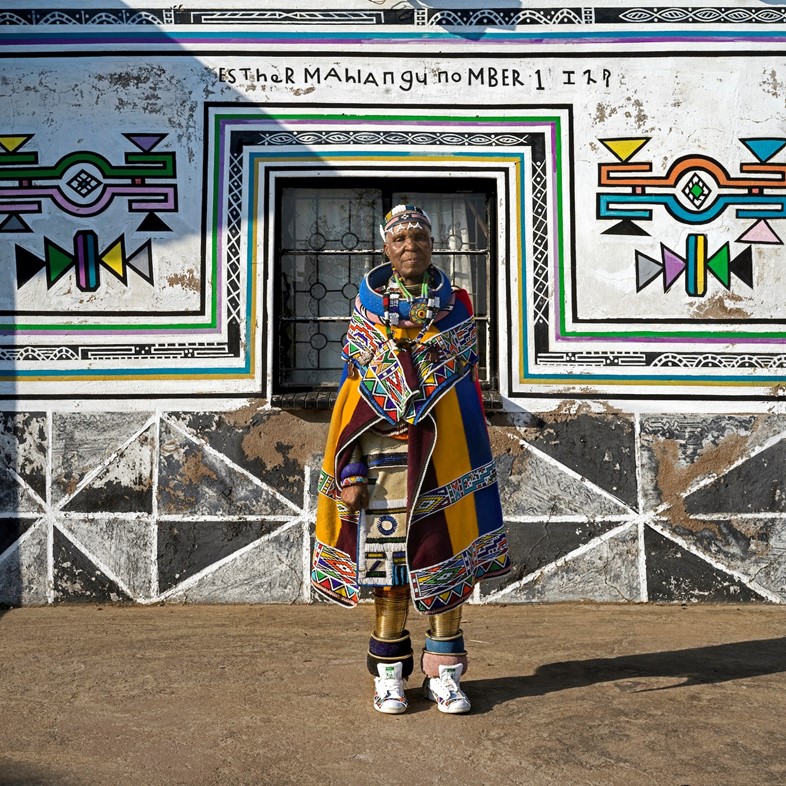

This one-of-kind vehicle is the result of breathtaking colour change technology, developed by BMW alongside electronic paper-display tech brand E Ink. The mesmerising art that adorns it, meanwhile, is the handiwork of Esther Mahlangu, the 88-year-old South African artist who has made it her life’s work to preserve and reimagine the tribal art practices of her community, the Ndebele, located in the Gauteng, north of Pretoria.

Mahlangu’s latest BMW collaboration is one of several key events in what is turning out to be a major year for the octogenarian painter: in February, the first retrospective of her work opened at the Iziko Museums of South Africa in Cape Town – a show that will tour globally over the next two years. Next month, Mahlangu’s work will feature in the 60th Venice Biennale exhibition Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere, curated by Adriano Pedrosa, and in November Thames & Hudson will publish a biography of her extraordinary life and career.

“Esther’s entire work is a protest against forgetting,” says the Swiss art curator and critic Hans Ulrich Obrist, who also penned the Thames & Hudson monograph and is in attendance at the NOSTOKANA’s unveiling. “It’s about the Ndebele tradition … [which] she felt was on the edge of being forgotten. She has devoted her entire life to maintaining its visibility.”

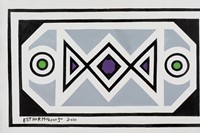

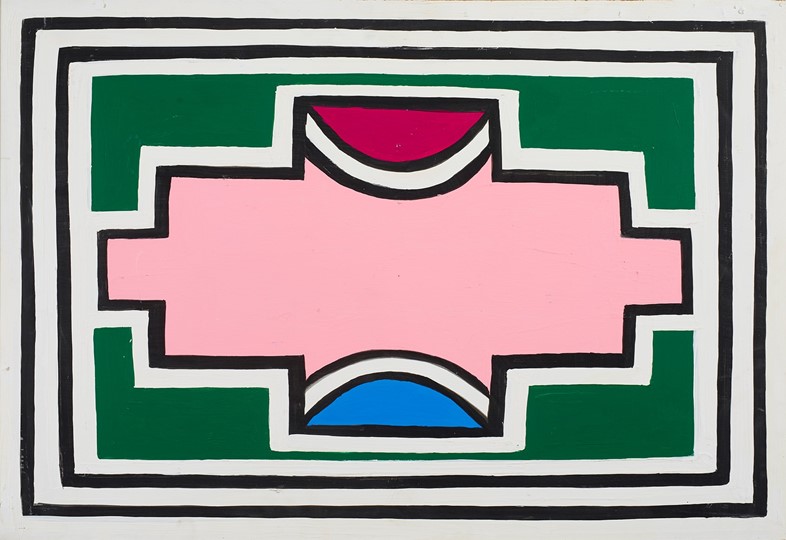

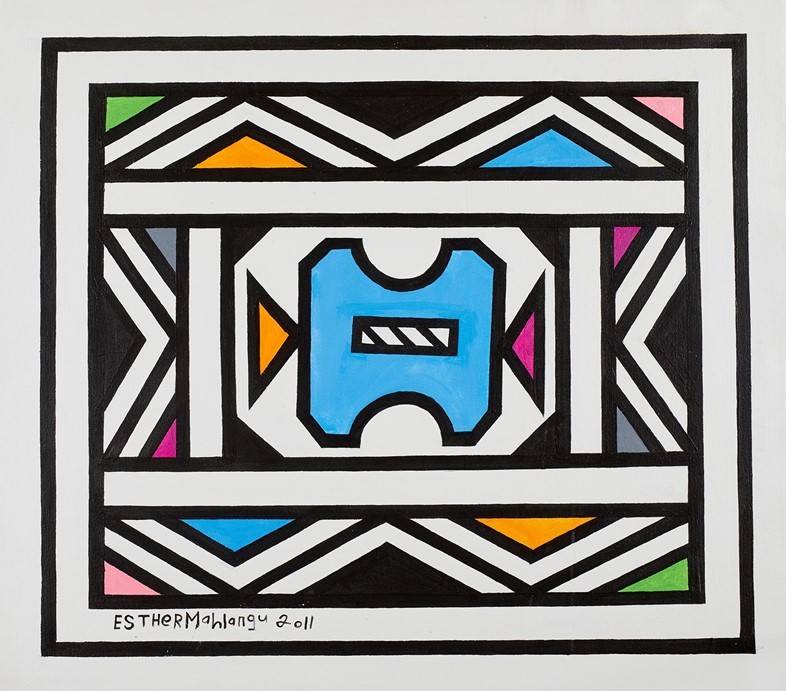

In Ndebele culture, bead-working skills and wall-painting techniques, centred around vibrant geometric designs outlined by black borders, are passed down from mother to daughter. A decorative practice that has long enlivened Ndebele textiles and architecture, the art’s apparently abstract forms are in fact founded on a centuries-old system of signs and symbols that denote everything from significant life events (such as marriage) to social status and spiritual beliefs.

Mahlangu received her artistic training from her grandmother and mother as a child in the early 1940s. “I would continue to paint on the house when they left for a break,” she once explained. “When they came back, they would say, ‘What have you done, child? Never do that again!’ After that, I started drawing on the back of the house, and slowly my drawings got better and better until they finally asked me to come back to the front of the house. Then I knew I was good at painting.”

In the years that followed, driven by remarkable determination and burgeoning creativity, Mahlangu began expanding upon the Ndebele customs. She started using acrylic paint – applied freestyle with a chicken feather, as per tradition – to broaden her colour palette and introduced her own iconography into the mix, resulting in the distinct visual lexicon with which she has since become synonymous.

Her hope was always to bring happiness through beauty, and to uphold what she feared was a dying art form: she soon began passing on her skills to other members of her community, including boys and men, and would later found an art school in her home’s backyard. “My innovations are a natural progression of the ancestral knowledge passed down through generations,” she tells Obrist, in the monograph. “We rejoice for those who have paved the way for us in life. We come from the earthly realm with joy because there is something that will help us, something desired by many.”

But it wasn’t until she took a job at the local Botshabelo Museum that Mahlangu decided to expand into new mediums, she tells AnOther. Realising their commercial potential, she began transferring her designs to vessels and canvases that could then be sold. Another major turning point came in 1989, when, having caught the attention of curator Jean-Hubert Martin, the artist was called upon to participate in the now-legendary group exhibition Les Magiciens de la Terre at the Pompidou in Paris.

Mahlangu boarded her first ever flight for the purpose and arrived in the French capital to paint an exact replica of her hut in South Africa. She was one of the show’s most talked-about stars, wowing attendees and art world connoisseurs alike – including a young Hans Ulrich Obrist – with her skilled command of colour and form, and imaginative fusing of indigeneity with modern abstraction.

Two years later, she became the first woman – and first African – artist to participate in the BMW Art Car project, following in the footsteps of Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein in hand-decorating a luxury sedan. The car’s celebrated design epitomises Mahlangu’s ability to render the traditional contemporary, and saw her heralded a national icon in her native country.

“I have always been open to collaborations,” Mahlangu tells AnOther. “It allows me to explore new mediums, to present my artworks in new ways and to expose them to larger audiences” – something, she says, she’d always dreamed of doing but which the success of the Pompidou show and the art car showed her was truly possible. The artist has continued to undertake collaborations ever since, alongside her own lauded practice, migrating her work onto everything from aeroplanes to Comme des Garçons shoes, and, in 2016, the interior panels of a BMW Individual 7 Series.

It was a photograph of Mahlangu sitting in that car – dressed, as always, in traditional Ndebele attire and looking just as vivacious as her artworks – that enabled Stella Clarke, a research engineer at the BMW Group, to convince her colleagues of the merits of colour change technology. “She was sitting in the passenger seat looking at the dashboard and on the display there was the text: welcome Esther Mahlangu,” explains Clarke of the shot. “In my pitch, I said, ‘Imagine getting into your car and not only being greeted by it’ – and I zoomed in on the text – ‘but by an entire custom interior view’. Then I zoomed out to show Esther with a huge grin on her face, looking at her personalised dashboard. And that was the moment they got behind the technology!”

And it is exactly this effect that has spurred Mahlangu on in her endeavours, while no doubt accounting for the enduring and wide-reaching appeal of her endlessly energising oeuvre. To conclude his speech at the NOSTOKANA event, Obrist shared one of his favourite quotes from the artist, which will feature in his book and which he feels perfectly encapsulates her outlook: “Art is something that brings joy and pride when I look at it. When others see my art and feel hope or happiness it feels like a celebration, a ceremony of life’s beauty … To those who want something from me, I offer hope. When I look at myself and my work, I see happiness and joy, like the early morning. It’s about sharing that feeling of contentment and celebration with others.”

“Then I Knew I Was Good at Painting”: Esther Mahlangu, A Retrospective is at the Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, until 11 August 2024. The Venice Biennale runs from 20 April – 24 November 2024. With special thanks to BMW Group Culture.