Kristina Shook talks about her mother Melissa Shook’s Daily Self-Portraits (1972–1973) series, which offers an expansive and inviting meditation on womanhood

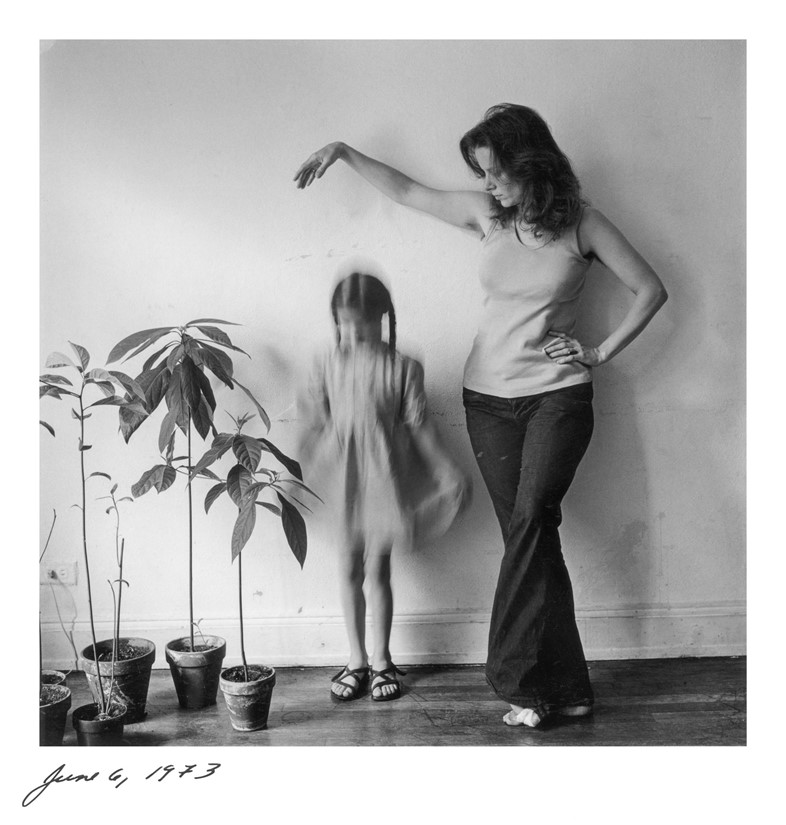

Growing up on New York’s Lower East Side in the late 1960s and early 70, Kristina Shook lived a decidedly bohemian childhood. Her mother, Melissa Shook (1932-2020) was a photographer, educator, and free spirit who created a magical world for her daughter amidst a community of downtown artists. “Me and my friends ran around naked. We danced in lofts. We had so much freedom,” says Kristina. “I would put paint on the wall and Melissa would say, ‘That’s beautiful!’”

For as long as Kristina can remember, her mother’s camera was always there, a third eye that happily shared in their daily lives, chronicling fleeting snippets of memory with a tender bliss that belies profound tragedy. At the age of 12, Melissa Shook’s mother died and with her passing, the young girl suffered traumatic amnesia. Her memories of her mother were erased and what remained was an alcoholic father exhibiting extreme negligence. “I think Melissa was coming out of a sad childhood,” says Kristina. “I loved my grandfather but I met a completely different person. He listened to me. He supported me. He loved me. I don’t think she ever felt loved by him. He did try and show it, but it was too late for Melissa.”

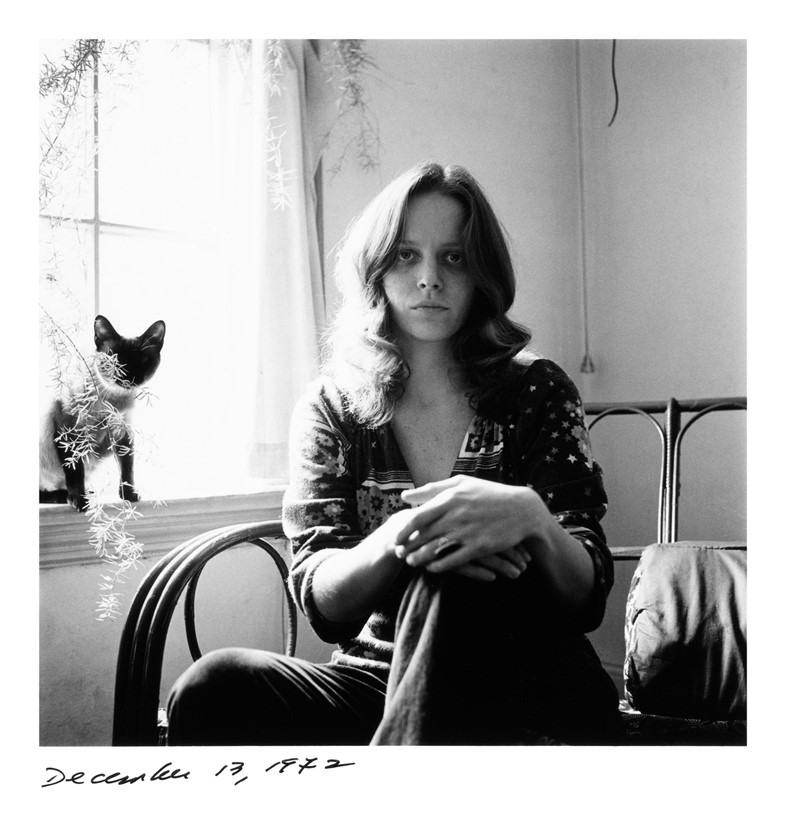

As a single mother, Shook carried existential terror; when Kristina was 12, she turned to the camera to mediate her fears. Melissa photographed her daughter for the series Krissy, before turning the camera on herself on 1 December 1972, after a toe injury forced her to be still. In her very first self-portrait, Shook sits on the sofa, head and torso hidden behind The Village Voice, while literally dipping her proverbial toe in the water before deciding to dive in the deep.

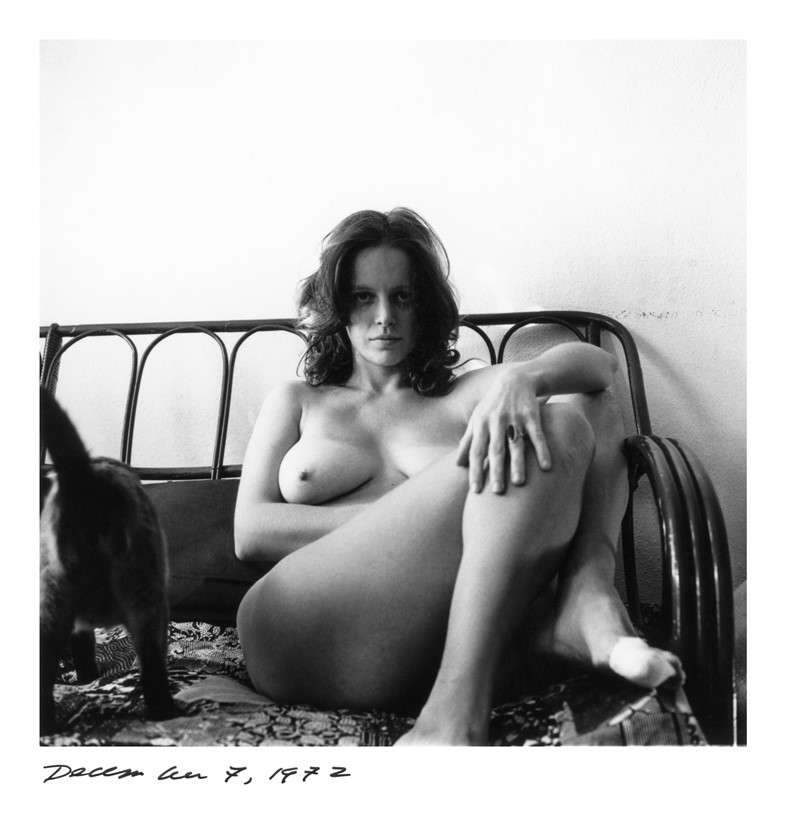

In this moment of guarded intimacy, Shook slowly began stripping away the proverbial veils that had enshrouded her entire life, setting forth on an epic exploration of self inscribed within the domestic interior among family and friends. Every day until August 1973, she set up her medium format camera, crafting an intimate portrait of herself as both artist and muse. With the opening of Daily Self-Portraits 1972–1973 in Kansas City, Missouri, and the publication of an accompanying book of the same name (TBW Books), the complete series of 192 photographs comes into view for the very first time, offering an expansive and inviting meditation on womanhood.

At a time when the subject of identity, family and domestic life were largely excluded from the provenance of fine art, Shook reimagined the self-portrait as a documentary practice. Casting herself as subject, she strips away the veils to reimagine the female nude as a psychic landscape: seductive, exciting, awkward, fragile, strong and grotesque, unafraid to confront, explore and expose the good, bad, and ugly to the world. Perhaps it was a way to reclaim her body for herself and to find a love she had been denied by so many men who coveted her bombshell physique for their own use.

Shook began the project by writing brief diary entries to accompany the photographs, laying bare her starkest self on the page. Kristina, who learned of the diary’s existence after her mother’s death, says, “Melissa wrote about a paragraph or a couple of sentences, but they’re very raw and you know right away that she was really struggling economically and physically in relationships. There was a desperation to be loved. She writes about these personal feelings, things she told her therapist, and worries about how to live within the body that she was given.”

Shook received guidance to set the writing aside and focus only on the photographs, which she eventually did. No longer giving voice to her mindset, Shook embraced the freedom of allowing her body to speak its truth,and discovered the deeper rhythms of existence itself. “The Daily Self-Portraits were natural. It was just like, this is how we live: we have brown rice and broccoli; Melissa takes a daily self-portrait every day and I hang out with my friends. It was very organic,” says Kristina. “I didn’t understand why she had to take them but they were fun because our downstairs neighbours would come up or friends would visit and she would do pictures with them. She didn’t want you to stand and pose; you just had to be a free bird. You could do what you wanted.”

Shook struck the perfect balance between chaotic and disciplined, showing up almost every day to see what might happen when she let loose and peered inside her soul. Blessed with an hourglass physique that created commotion wherever she went, Shook integrated her nude body into her exploration of self. In these moments of exquisite vulnerability, she becomes Pandora opening the box and releasing the unspoken truths inscribed in the flesh of a woman, artist and mother, now in her thirties and questioning her identity.

“Melissa was in front of the camera asking, who am I?” Kristina says. “Everybody comes with a certain amount of damage and what do you do with that? I love that Melissa was like, I can't fix it but I’m gonna make photographs from it. It had to be done in order for her to live and breathe.”

To Prove that I Exist: Melissa Shook’s Daily Self-Portraits, 1972-1973 is on show at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri until 8 August 2024. Daily Self-Portraits 1972–1973 is published by TBW Books, and is out now.