Jason Koxvold’s new photo book, Engage and Destroy, is a typological survey of soldiers before and after their seven-month training and a rare insight into the military’s human production line

Jason Koxvold is not what you would call a conventional war photographer, and yet, for the last decade, he has made global conflict the focus of his work. Away from the front lines, the British-born, New York-based photographer has instead documented war as a conduit for capitalism in a post 9/11 world, investigating its cultural imprint across the US and the Middle East. In his 2017 series Black Water, for example, Koxvold took viewers behind the curtain of conflict, from military fairs and satellite control rooms in the US, to training bases and mess rooms in Kuwait and Afghanistan. At its heart, the project sought to answer what an interminable War on Terror looked like as an industry.

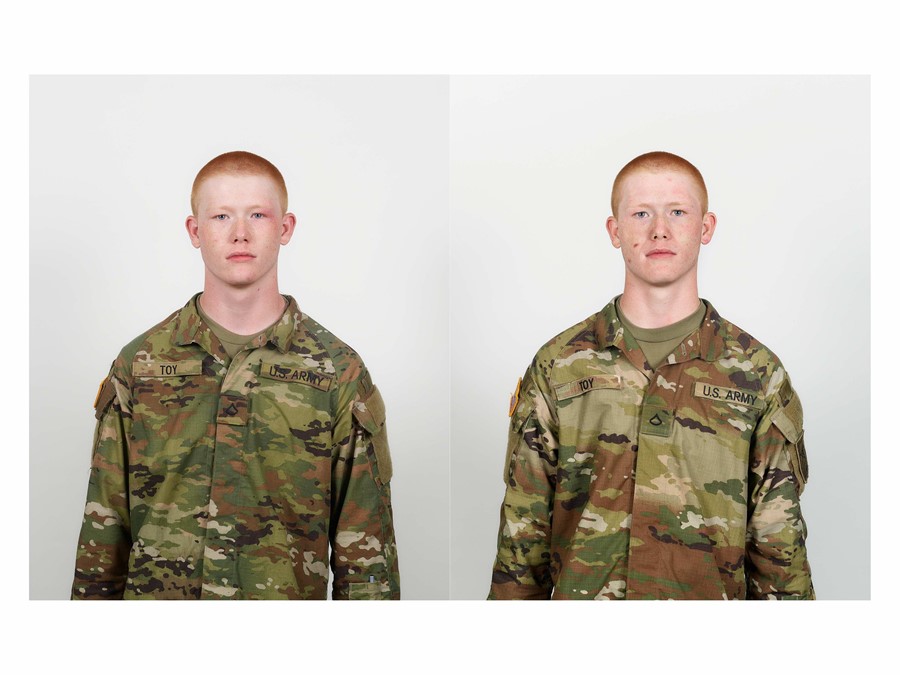

For his latest publication, Engage and Destroy, a follow-up to Black Water that will ultimately be unified under one title, Koxvold delves deeper into the legacy of that particular conflict and its continued reverberations across the US. Shot between May and October 2021 at Fort Moore, a US Army base on the border of Alabama and Georgia, it is both a typological survey of recruits before and after their seven-month basic training, and a rare insight into the military’s human production line.

“It was testing a hypothesis in some way,” says Koxvold. “I was curious to see how significantly these people are changed by the experience of getting their asses kicked for seven months.” The book’s double-spread twin portraits do not offer a straightforward answer. In some, the change is stark: excess is trimmed, cheeks hollowed, features hardened and eyes that formerly betrayed innocence, a little fear even, become cold and vacant. Others, as Koxvold points out, “Look identical as on day one, so in that regard, the hypothesis failed. But in another regard, you see physical marks on their faces, sometimes from violence. And those marks are presumably reflected internally.”

Interspersed among these portraits are black and white photographs of recruits in hand-to-hand combat training. Shot under harsh strobe lighting with a close focus, they bring us within inches of the action, framing the tangle of bodies in a way that remains ambiguous. “There was something really interesting about this tension,” explains Koxvold. “Some images are pure violence, and some, despite the fact the faces are bloodied, are quite tender.”

Tapping into a timeless juxtaposition between tenderness and violence, vulnerability and machismo, Koxvold’s photographs find themselves in good company. Like the stifled homoeroticism in Claire Denis’ Beau Travail (1999), or the disorientating camera work of Steve McQueen’s Bear (1993), the intimacy of these photographs invites the viewer to become a participant, both in the image and within a wider consideration of masculinity.

In this sense, the series shares parallels to the first half of Stanley Kubrick’s 1987 anti-war film, Full Metal Jacket. Like Kubrick, Koxvold reveals a behind-the-scenes view of the physical and psychological abuse new recruits must endure in order to attain manhood within the US military. Both works present this process of masculinisation with distrust – the disassembling of innocence, virtue and critical thought to accommodate cold-blooded ruthlessness and unquestioning discipline.

For Koxvold, these images reflect the impact of a wider cultural tolerance within the US for conflict, something he attributes to the insidious influence of its never-ending involvement in the Middle East. “As a father to two young children, I see so much war in the culture here,” says Koxvold, “even when I look at the other kids in their school who are around eight years old.” Despite US Army enlistment numbers steadily declining for the last 40 years, Engage and Destroy identifies an appetite for war and vengeance within the American collective consciousness that appears far from sated.

Engage and Destroy by Jason Koxvold is published by Gnomic Book, and is out now.