A new retrospective at Paris’s Fondation Louis Vuitton demonstrates the ongoing potency of the Russian-American painter’s transcendental oeuvre

Mark Rotho once explained that the reason he decided to pursue painting stemmed from a desire “to raise [the medium] to the level of poignancy of music and poetry”. And, at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, a brilliant new retrospective of the revered abstract expressionist’s work reveals the various twists and turns in his remarkable journey towards creating “a language of feeling” in paint – to quote his friend and contemporary Robert Motherwell.

Set in the foundation’s vast Frank Gehry-designed building, with its exterior of sweeping curves resembling billowing ship sails, the exhibition of 115 works unfolds with a rhythm appropriate for an artist who was enthralled by music and theatre. “This fabulous, dramatic building, with its wonderful individual galleries of different shapes and sizes, allowed us to tell a series of stories,” says Christopher Rothko, the artist’s son, who co-curated the exhibition alongside the foundation’s artistic director Suzanne Pagé. “We’ve made vignettes that allow you to travel between each part of [Rothko’s] career.”

Born in Dvinsk, Russia in 1903, Rothko and his Jewish family emigrated to Portland, Oregon when he was ten. He was a precocious student, who attended Yale for two years, before dropping out and moving to New York in 1923, where he began training as an artist. But it is Rothko’s work from the 1930s – following an influential encounter with the American modern painter Milton Avery, who informed his early treatment of colour and application of paint – that we are first introduced to here. Nudes, interiors and urban scenes – including various depictions of New York subway stations, all sharp architectural lines entrapping elongated figures – feature, as does a deeply mysterious self-portrait showing the artist in dark glasses.

But Rothko didn’t linger on figurative or realist elements for long. Declaring a dissatisfaction at his attempts to portray the human form (“a time came when none of us could use the figure without mutilating it,” he later wrote of himself and his peers), by the mid-1940s, his paintings had evolved into a spellbinding blend of mythical surrealism and abstraction, drawing on Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy and the theatre of Aeschylus. As the Second World War raged, Rothko, haunted by his memories of the pogroms of his childhood, appeared to find a greater means of expression in what Pagé describes in the exhibition catalogue as “the distorted image of archaic heroes as monsters with hybrid, split, dismembered, shredded bodies”.

Examples of these are represented in a “fabulous transitional room”, as Christopher Rothko describes it, where visitors can see “step by step, as Rothko approaches the ultimate colour field form”. One long wall in this room – which, Christopher explains, took the curators seven or eight hanging attempts to get right – offers an “experiential” understanding of Rothko’s shift to all-out abstraction, growing out of his so-called multiforms (large-scale paintings, freed from the easel, made up of blurred patches of extraordinarily evocative colour).

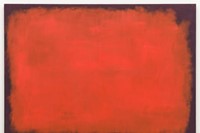

These vast, vibrant works dance and dazzle, demonstrating Rothko’s mastery of colour and its various combinations and his near miraculous ability to encapsulate light and space on canvas. “Here, you can see him working out the forms, working out the boldness to say what he wants as directly as possible,” explains Christopher. And work it out he does, as evidenced by the arrival at his iconic “Classic” paintings of the early 1950s, wherein, Pagé explains, “rectangular shapes of radiant colour with undefined edges are arranged, usually vertically, in a binary or ternary rhythm”.

At this stage in the exhibition, it is interesting to observe the hush that falls among its viewers. Conversations from here on cease or are carried out in quiet whispers, demonstrating the spiritual power of these monumental canvases. “I paint large pictures because I want to create a state of intimacy,” Rothko proclaimed. “A large picture is an immediate transaction; it takes you into it.” And indeed, these works demand active participation, the onlooker a galvanising force in Rothko’s vision for his art. “I’m after an experience for the viewer,” he said, “one that involves his emotions as well as his intellect.”

In the rooms that follow, we are privy to some of Rothko’s most emotionally searing and transcedent pieces, from the dark, wine-hued Seagram Murals, originally intended to adorn a New York restaurant but ultimately gifted by the artist to the Tate in London, to the smaller Black and Gray paintings. Sombre in tone, more minimal in form, these are shown alongside spindly Giacometti sculptures to sriking effect as per Rothko’s original intention for the works, which he began as part of a never-realised commission for the UNESCO building in Paris.

The range of feelings Rothko’s mature works evoke spans meditative calm, radiant joy, existential angst, gloom, grief and beyond, which is exactly what the painter intended. “He doesn’t want us to go through life placidly,” says Christopher, who was just six years old when his father, in a state of ailing mental and physical health, took his own life. “He wants us dealing with the really hard questions: How are you going to make your life meaningful? What happens after you die? Why are we even here? I think that’s what he meant when he spoke of his work containing violence. You see it in these otherwise placid rectangles that have actually a lot of brushwork, or in the very active fields in the last Black and Gray paintings, which are agitated. He wants to stir us up.”

In today’s turbulent world, where we are bombarded by images and information on all sides, Rothko’s mode of abstraction feels particularly ameliorative for this exact reason. Like the best pieces of music or poetry, these canvases invoke highly personal responses from deep within, while allowing us the time and space to process them in a way that is truly cathartic. “It is a modest goal to make the viewer aware of his own potential feeling, to create an association, and to create it with the simplest form or colour structure,” the artist once said. And yet the realisation of this, as this exhibition proves, is nothing short of genius.

Mark Rothko is on show at Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris until 2 April 2024.