Shot over the past 11 years, the Danish photographer’s first book takes an art historical subject – the reclining nude woman, as portrayed by men – and makes it her own

“Like all good stories, this one is best lived in reverse,” writes Stephanie LaCava in the afterword for Love Me Again, the first book from photographer and filmmaker Michella Bredahl. The publication features a series of portraits, of old friends and intimate acquaintances (including LaCava) taken over an 11-year period from 2012 to 2023. But its origins can be traced back much further.

Bredahl’s initial plan had been to make an archival book about her childhood spent in “vulnerable residential area” – social housing – district Høje Gladsaxe on the outskirts of Copenhagen. “My mother used to take photos of me a lot. She would photograph me in my bedroom and her bedroom, all around our apartment. It was a bubble – me, my mum, my sister and the camera,” Bredahl tells AnOther from Paris. She took her mother’s portraits to Loose Joints, who, as contemporary photography publishers, instead saw potential in Bredahl’s own work. The publishers combed through and selected from hundreds of her images, and worked alongside Bredahl as she created new ones.

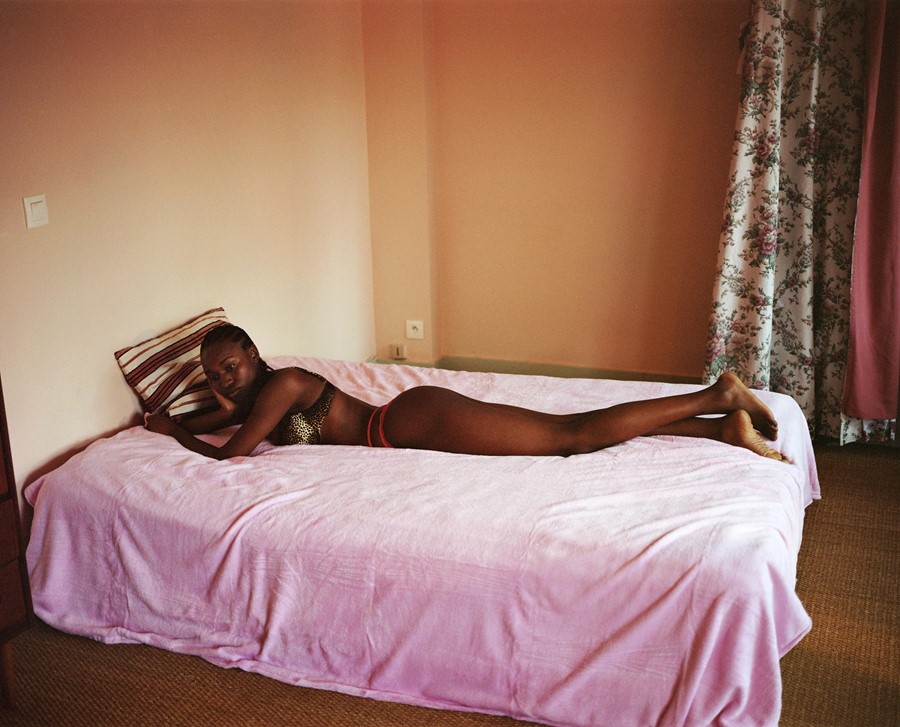

In Love Me Again, the reclining body in particular stands out. Shooting in locations such as Paris, New York, Mexico City, as well as her native Copenhagen, Bredahl largely rejects the outside world for interior spaces, her subjects pictured in bedrooms, bathrooms and living room floors. While male artists have historically used the reclining nude as a funnel for female idealisation, Bredahl’s supine bodies, of varied identities, dressed in different degrees of dress, are beautifully imperfect, quietly languorous amongst strewn sheets and cluttered floors, both alone and accompanied. Bredahl cites Chantal Akerman and Tracey Emin as influences, a filmmaker and artist who also worked to rescue the recumbent body from the male gaze. Yet Bredahl’s interest in lounging stems from something deeper. “It refers to my mother. She wasn’t well. She was always lying down and this is an image that has stayed with me.”

Bredahl’s Madonnas are similarly evocative. The book features several images of her friend Klara with her daughter, Bobbie. In the first they are photographed in the bath; taken via the ceiling mirror, their image is fractured into a triptych. Later, she is pictured in a sumptuous Parisian hotel room, made messy with her daughter’s stuff. Her face is covered with her hair as she kisses Bobbie, while she looks directly at the camera. In other portraits, children who perhaps seem too old for it, are cradled by their mothers.

When she was 13, Bredahl moved away from her home to live with another family in a more affluent area of Copenhagen. But she feverishly returns to this time in the content of her images. “I think I’m looking for the people and friends I was separated from at that age,” she explains. Young women and girls populate the portraits, with Bredahl proudly capturing an incipient sensuousness that can be a site of moral anxiety. A group of sisters, one of them a former student of Bredahl, bear their midriffs – “When I was 12, I loved to show my belly,” she recalls. The shots of the actor Vic Carmen Sonne, taken multiple times over the course of seven years, at times resemble Balthus’s controversial paintings of young girls. In one she is in bed with her feet in the air, balancing a cat on her feet in her lilac bedroom. “I make my own mark on the poses I see being portrayed by men through the history of images,” says Bredahl.

Clashing, chintzy pattern and texture in the photographs are a sensorial memory of how Bredahl’s mother decorated their house, but also refer to her hatred of white studios. From the ages of 14 to 21, Bredahl worked as a model and while this experience introduced her to photography, it also left her with questions about the ethics of photography, and in particular the safety of her subjects. “One thing I hated was that I never saw the images before they came out. It was my body and my soul and yet I had no say,” says Bredahl. “Some of my models are really close friends of mine, and from the beginning, I always try to involve them in where we are going to shoot and how. And they always have a last say on the images if they don’t like them.”

Bredahl shot LaCava in L’Hotel on Paris’s Rive Gauche. The pair became friends over the internet, and the day of the shoot was their first physical meeting. L’Hotel was also a location used by American photographer Nan Goldin, who is a spiritual, if not aesthetic, influence on Bredahl. “I look at her books and just feel like I should be in there. And when she talks about obsession, being obsessed … I always have my camera on me,” she explains. As well as working with old friends, she has met models on the streets, in classrooms and on Instagram, which then turn into close, collaborative friendships. “There are so many ways in which photography can be used to benefit just one person,” says Bredahl. “But like Goldin says, there’s always the other side. I feel like I belong to that side, and [so do] all my friends in the book. We live from the heart.”

Love Me Again by Michella Bredahl is published by Loose Joints and is out now. Bredahl’s solo show will open at Shoot the Lobster on November 4 in New York.