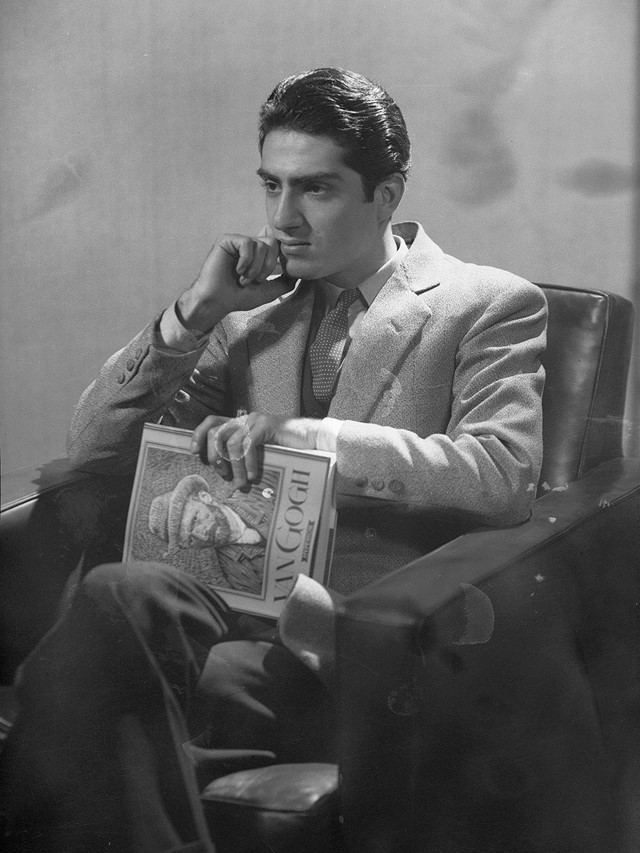

A new exhibition in LA explores the life and work of Van Leo, an Armenian-Egyptian photographer whose self-portraits offer a nuanced exploration of gender, race and class

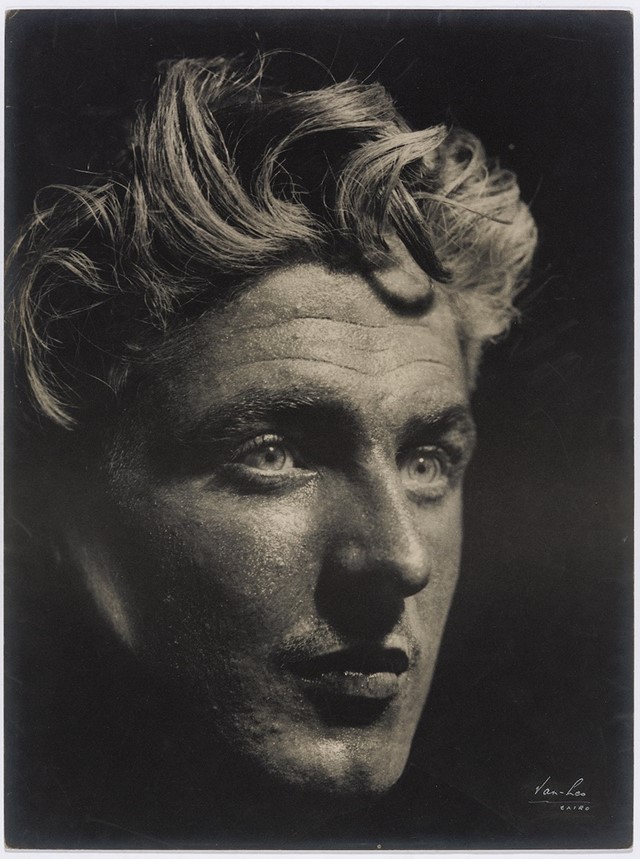

The desire to obsessively self-document is often understood as a contemporary phenomenon, driven by the need to forge compelling visual identities on social media. But long before selfies entered the lexicon, studio photography offered one self-portraitist the chance to inhabit the most expressive of alter-egos. Van Leo was the pseudonym of Levon Boyadjian, an Armenian-Egyptian photographer who had a booming photography practice in Cairo from the 1930s.

Taking almost 400 self-portraits throughout his life, he inhabited the flamboyant, chameleonic role of Van Leo. His series of self-portraits offer a nuanced exploration of gender, race and class, as he shifts with ease and humour into different costumes and identities. The Hammer Museum in Los Angeles is now showing a selection of works from his first experiments in the studio in the 1930s, through to his alter-ego self-portraiture practice to more formal studio work which lasted into the 1990s.

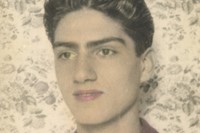

“Van Leo’s work anticipated the selfie boom to come,” says writer and curator Negar Azimi, who has worked on the show independently with the Hammer Museum. “As early as the 1930s, as a teenager, he was indulging in the self-fashioning capabilities of the camera, experimenting extravagantly with costume, setting and light to transform himself into a prisoner, Zorro, a bejewelled woman, along with dozens of other guises. Van Leo was absolutely ahead of his time, but also firmly a product of his time: the film industry, with all of its powerful imagineering, was booming, and he, a young man in Cairo, was a devotee.”

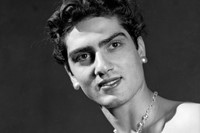

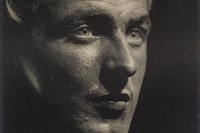

One image from the 1940s depicts the artist with a pencil moustache and simple suit and tie, inhabiting a conventional image of formal masculinity; another from 1937 is a coloured black and white image, showing the artist with pink-tinged lips against a soft floral background; a shadowy portrait from 1945 shows Van Leo coolly smoking a cigarette wearing white sunglasses. Amongst his self-portraits, there is also a revolving group of visitors, from kilt-clad WWII Scottish soldiers to local dancers.

“I’m drawn to the handful of images that have a comedic bent: a man crossing his eyes; a woman carrying a teetering candelabra on her head; a woman photographed at the base of the Giza pyramids in what appears to be her bra and oversize underwear,” says Azimi. “Van Leo, it turns out, could be a ham.”

Van Leo was originally inspired by the allure of Hollywood postcards, which captured the era’s movie stars draped in glamorous outfits with dramatic lighting. He collected these during his teenage years and started working with a professional studio photographer soon after to service the influx of international travellers and residents looking for classical photography. He opened a studio with his brother and then on his own in the 1940s, experimenting with the same large format photography until his final works in the late 1990s.

“In certain circles, Van Leo is known as a photographer to the stars, famous for capturing members of the Egyptian film industry, what constituted the Hollywood of the Arab world,” says Azimi. “Which is to say, his images of Omar Sharif, Sherihan, Rushdy Abaza and other Egyptian stars have long been celebrated. Still, I found that his portraits of the lesser-knowns, the aspiring actors and actresses, and even ordinary people whose names we don’t know, often touch me the most. They smoulder and pulse with life and longing.”

In his fluid relationship with the camera, Van Leo avoids any one aesthetic or trend, instead embracing and celebrating the ability to shift between identities, each as much a part of him as the next. Many of his self-portraits challenged the rigid beliefs of their time, and indeed, some push on taboos and binaries that permeate to this day. While he received critical acclaim in his lifetime, Azimi notes that there was a certain mystique surrounding him, which further played to the balance of truth and fantasy so woven throughout his work.

“I think the film industry would have been the framework for their reception, and in fact, in some press from his time he’s compared to Tyrone Power,” she says. “Bafflingly, there’s some Egyptian tabloid press from the 1950s that declared he had travelled to Hollywood to photograph Clark Gable, Kim Novak, Marilyn Monroe, and others. The same articles note that he had fallen in love with an American heiress. Absolutely none of this is true. The provenance of these articles, with their fantastical nature, is a mystery. But it does point to how he was understood at the time; as a sort of Hollywood-adjacent enigma.”

Becoming Van Leo is on show at the Hammer Museum in LA until 5 November 2023.