The title of photographer Kyle Weeks’ latest project Good News goes back to his childhood in Namibia, when he would watch his father react to the news. The “constant stream of negative stories” he observed about his home country and Africa at large prompted a simple question in his mind: “Why is there never good news?”

The question would come back to Weeks years later in Ghana. “Plastic bags with catchphrases like ‘Good News’ are something you see quite often in Ghana,” he explains. “Similarly, taxis are regularly decorated with catchphrases stuck [to] their back windows. ‘Never Late’ is one that comes to mind.” When a young man arrived for a portrait session with Weeks, a plastic bag full of clothes carefully selected for the shoot in tow, he noticed that the bag read ‘Good News’. An ‘aha’ moment occurred, and the phrase became the working title for Weeks’ project.

Good News is the culmination of the six years Weeks spent photographing in Ghana, beginning in 2016. The vibrancy of his images – especially the resplendent and effusive portraits of Ghana’s youth – impart a sense of timelessness while gesturing towards the future, one that is hopeful and expansive. “I got there at a time when this creative energy was bubbling and bubbling,” says Weeks. The emergence of initiatives like Surf Ghana, a skate and surf collective, and the establishment of Ghana’s first skatepark, both in Accra, reflected the interests of an innovative, cosmopolitan and fluid youth culture. On his first trip Weeks spent the month walking the streets from sunrise and sunset, approaching people and photographing the environment. His visit happened to coincide with the Chale Wote Festival, the largest annual street fair in West Africa. The creative energy in Accra, as well as conversations he had with friends in his network who were living there, inspired Weeks to keep returning. He took somewhere between 12 and 15 trips in total.

“The youth [in Ghana] have such an authentic approach to creativity. They have a completely different frame of reference. It’s so authentic and unlike what I see in the Western world” – Kyle Weeks

Ghana has always attracted allure, inspiring creativity and extraction in equal measure. Before gaining independence from Britain in 1957 – the first country in Africa to do so – it was referred to as the ‘Gold Coast’, known to Europeans for its riches: gold, and of course, slaves. A wave of construction took place in Accra following Ghana’s independence, at the behest of its new president Kwame Nkrumah. Accra, with its Independence Square, newly-erected civic centres and monuments, evoked a civic spirit that represented the larger Pan-Africanist struggle.

Traces of this history leaps out from Weeks’ images, particularly photographs of the physical and built environment. In one, a trio of men gather around a swimming pool alongside a dilapidated diving board – a relic from a lost era. The men blend seamlessly into the landscape, their bodies, under Weeks’ view, turned sculptural. One of the men dips a bucket into the pool, now a makeshift well. In another, one finds an unexpected reference to Basquiat, one of his kings, carved into a rock.

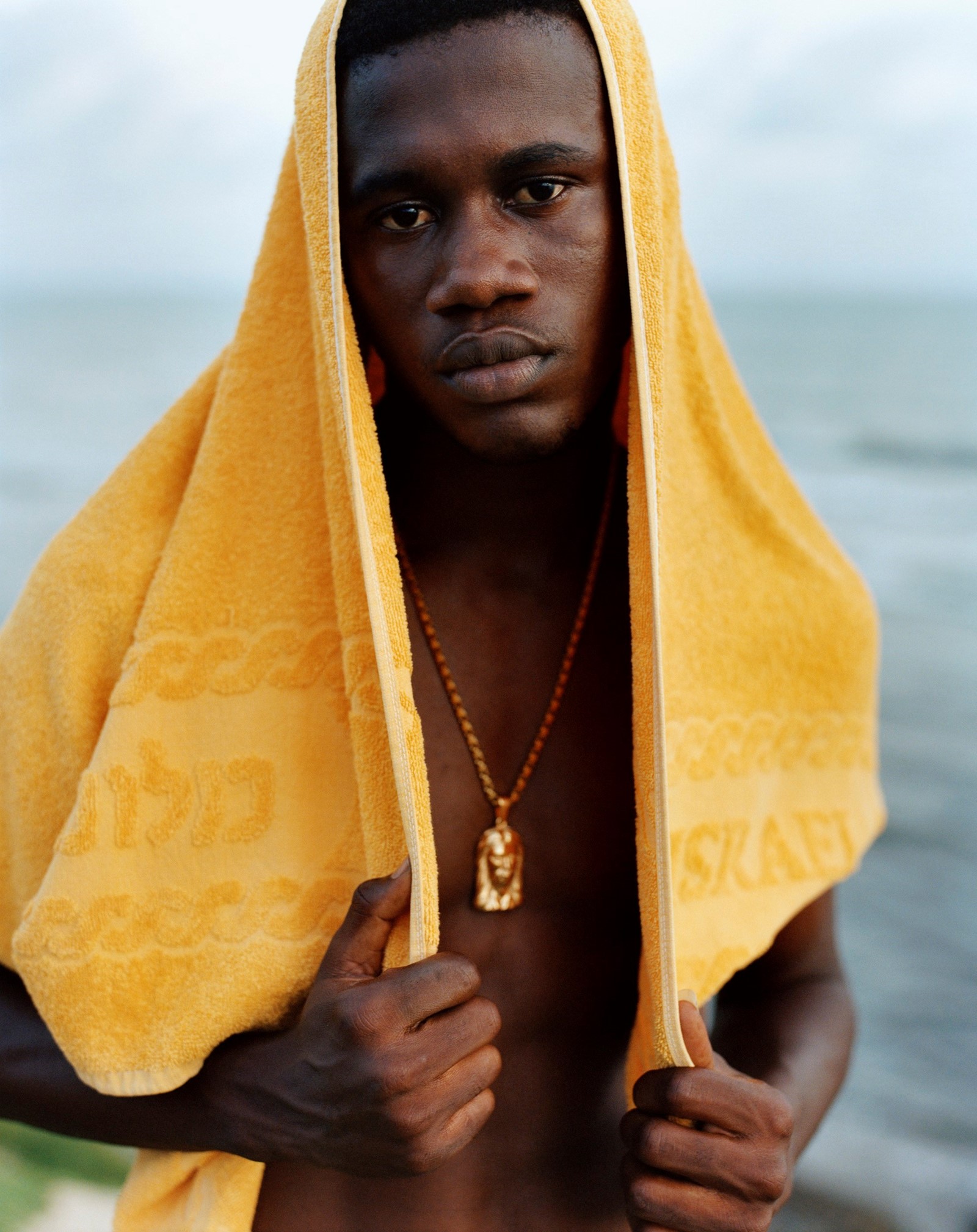

My favourite portrait is a black-and-white image of a young man named Spo. A washcloth drapes elegantly from his head. Spo’s posture, the textures and shadows of the cloth, recall Vermeer’s Girl With a Pearl Earring. The washcloth is a reference to a common image seen in the streets, of men wearing similar cloths to protect their heads from the sun. Here, two references crystallise beautifully in a single image.

Ghanaian photographer James Barnor chronicled a pre- and post-independence Accra. Like Barnor, Weeks captures a culture in the midst of transition and transformation. In Good News, one finds traces of photographers Philip Kwame Apagya, Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé, artists who also portrayed the evolving times and their subjects with a sharp, sensitive eye. The sensitivity of these photographers, Barnor in particular, resonated with Weeks. As an African of European descent – his roots span Germany, America and South Africa – Weeks often experienced apprehension and scepticism from Ghanaians when he asked to photograph them. Most assumed he was American. When he corrected them, a conversation about the validity of his identity as an African often followed.

The position of the white male photographer – roaming the streets, taking the city in, photographing its inhabitants freely – can justifiably evoke scepticism. The tradition of the roving white male photographer has its roots in ethnography, a branch of anthropology concerned with describing the traditions and customs of individual cultures. On the African continent, this description has often existed as a form of ahistoric capture, Westerners depicting non-Westerners as they saw fit. As an ‘insider-outsider’, Weeks is keenly aware of these complexities and doesn’t shy away from them. “I’ll always look like an outsider in Africa,” he says. “People on the street would assume that I [was] working for a news channel or trying to depict some facet of their society [or] culture they might not be proud to show the Western world, if I can call it that.”

Weeks started carrying images he’d made previously to show people what he was focusing on. “I was predominantly approaching younger people on the streets. Once they [saw] people of similar age dressed the way they are in these photographs, there was immediately this eagerness to want to participate,” says Weeks. By his third year into the project, he had built a network of people who were advocating for the project, connecting him with people to photograph.

To build a sense of trust, Weeks says “trying to figure out what kind of methodology or approach I [could] employ to try and bridge social or cultural gaps between myself and the people that I was photographing” was crucial. “Some of my older influences are deadpan portrait photographers like August Sander,” says Weeks. “New Objective Photography is something that has really resonated with me, just in terms of not trying to bring too much of my own subjectivity to the images. Obviously, that's a grey area, because the work will always be my view of the world. [I want] to photograph people in a way that also feels objective, in a way that they have also been given a space to really present themselves and represent themselves through my lens.”

As with his previous bodies of work – photographing the OvaHimba, considered the last semi-nomadic people of Namibia – collaboration and time were crucial elements. “Fostering and nurturing these relationships and building trust is so important in the work that I’m doing because I’m often photographing environments or cultures that are not mine,” Weeks explains. “Really taking the time to build relationships with people is something that has been important to me since the first long-term project that I did in Ghana. It was just a matter of returning often, and not just dropping in and taking something and disappearing. That’s my ethos in making work.” Ethnographic photography tends to crystallise history and culture in a particular, fixed way. Weeks’ photographs do the opposite. In them, time feels dynamic; it is energetic, constantly unfolding.

Weeks, now based in the Netherlands, tells me he struggles to find inspiration on the streets. “The youth [in Ghana] have such an authentic approach to creativity,” he tells me. “It feels like they’re not as influenced by what the rest of the world is doing because of what they have available to them. They have a completely different frame of reference. It’s so authentic and unlike what I see in the Western world.” Kantamanto Market, a second-hand market located in the central business district of Accra, is where many of the city’s most fashionable youth source their clothing. Home to thousands of traders selling deadstock clothes and other second-hand wares (referred to as “broni we wu” or “the white person has died”), Kantamanto became an important place to Weeks. Youth upcycle these “dead man’s clothes,” taking what has been disregarded by the Global North, using their genius to re-work and shape them into sui generis works of art. “What so many have disregarded is such an important facet of identity [there],” Weeks says.

That creativity can be found in the pages of Good News, in hairstyles and sartorial choices that feel classic, timeless and fresh. In one image, a young man wears a yellow and black mesh tank with a pair of red drawstring pants, cowrie shells and beads strung around his neck. His shoes cinch the outfit, shiny black Chelsea boots with a low heel and round toe. In another, a model punctuates a patterned suit, sharp enough, with two silver and leather chokers. It should all clash, but miraculously, it doesn’t.

Good News by Kyle Weeks is out now.