Use only as directed ...

Barbara Kruger is an artist who doesn’t take life lying down. An agitator of the first order who isn’t afraid to speak her mind, she has over the last 25 years developed an art practice that crosses all boundaries and breaks all codes. Image savvy and with a first-hand knowledge of how the media works from within, her striking combination of pictures and words reveal the stereotypes embedded at the heart of image culture. From billboards to postcards, shopping bags to bus shelters, T-shirts and even matchboxes, her photo-text montages have eo-opted the quotidian forms through which products are sold, appropriating the language of commercial art to address the encroachment of power within our everyday lives. Whether it is stereotypes of gender and race promoted through the mass media or the subjugation of the self seduced through the pleasures of capital, the perceived separation between a public sphere and private persona are for Kruger rendered obsolete. For Barbara’s work is about the war at home, a war enacted through images and words. She embraces a strategy of interference to expose the means by which representation legislates and defines us all. Obliterating the division that exists between art and life, between the media and a mediated self, her montages cut through the grease of modern living to reveal the mechanisms of power that lie behind. “I try to make work that incorporates the seductions of the culture that we live in but also makes us think,” she states when asked why her art continues to have such resonance in today’s society. “Any disjunction, any displacement, any messing with convention can help us to recognise the systems of control that surround us. Doubt can be an exercise in self-consciousness and criticality. lt can be an attempt to live an examined life.”

Standing in the centre of downtown New York with Barbara Kruger by my side is an experience to say the least. Just moments ago we attempted to take a photograph of Barbara outside the central law courts, a public building and bastion of the establishment situated a few blocks away from Ground Zero, and where Barbara had seen two portraits of President Bush and Dick Cheney hanging in the foyer. With their fake smiles and orange glow both men appear to be representatives of another race or as Barbara comments, “honouree residents of planet Debbie”. The picture had been a failure. No sooner had we taken out the camera than a host of security guards had descended on us from above, demanding to know what we were photographing and asking us to vacate the building even though the building in question was in fact a pavement located across the street.

“The present administration is absolutely tone deaf to what the world feels like and lives like. They have no understanding or even worse, no interest” – Barbara Kruger

It would appear that since 9/11 the division between government space and the public domain has been eroded. The US is on a heightened state of alert and the rights of individual citizens now take second place to the right of authority to dictate and direct their movements. Dissent is severely restricted and with the introduction of the new USA Patriot Act, described by Gore Vidal in a recent article in the LA Weekly as being essentially an anti-democratic act of despotism, things look like they are going to get a whole lot worse. For Barbara, who has witnessed the political climate in America swing from right to centre left and back again in under two decades, the current administration dug in at the White House is little more than an unelected regime. With its ill considered invasion of Iraq and unilateral policies that take little regard for its allies abroad, it appears to be heading for the rocks and is intent to take us all down with it. “This regime says things that are exactly the opposite of lived experience,” Barbara comments as we continue to wander aimlessly through the streets of downtown Manhattan. “To say that the Iraq war has made the world a safer place is to deny all the historical precedents that state otherwise. Such a statement can only be said by the most evil – and I never use this word – minds ever to be in the White House. The present administration is absolutely tone deaf to what the world feels like and lives like. They have no understanding or even worse, no interest.”

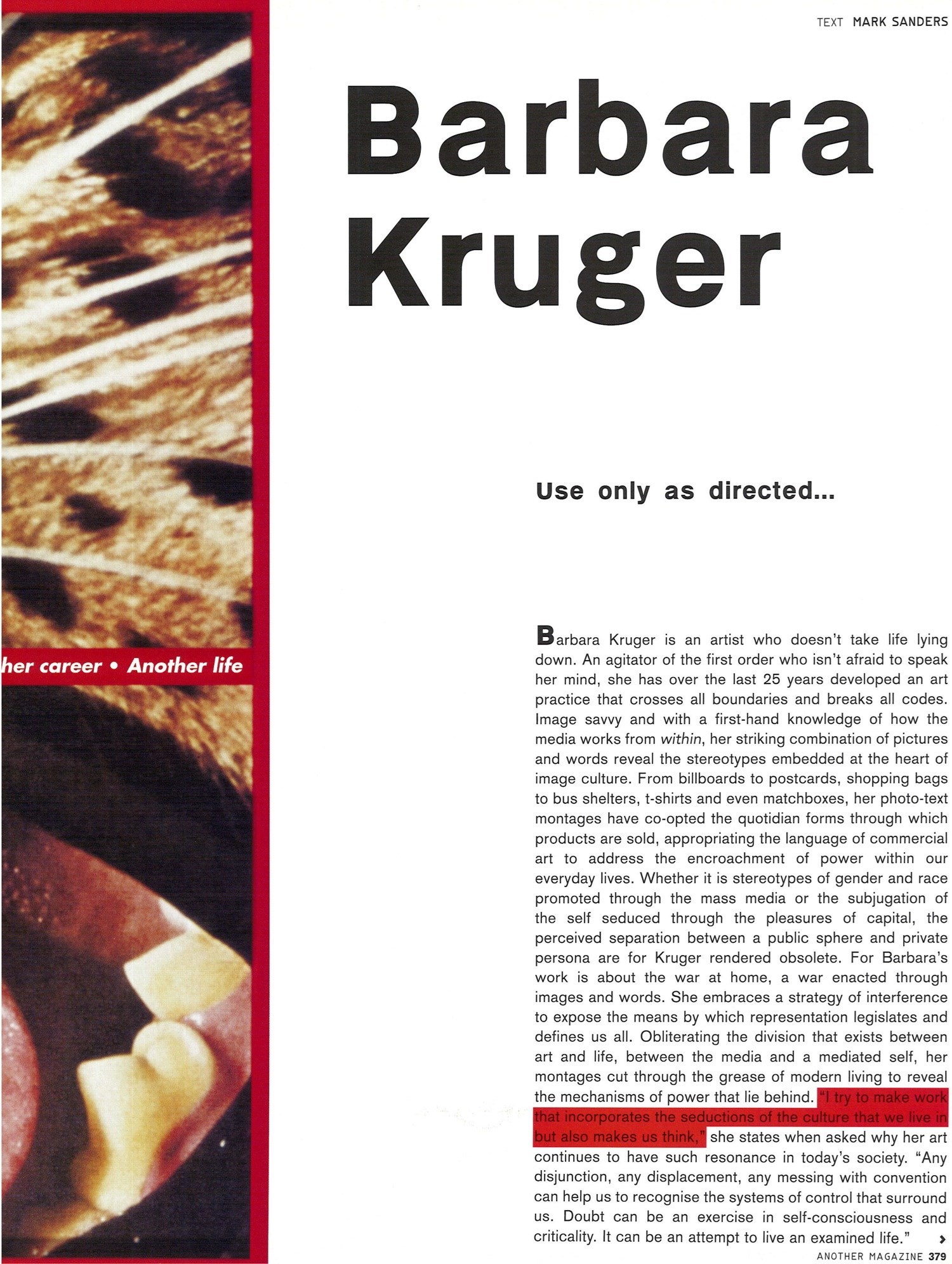

Back in 1983, Barbara Kruger questioned the issue of war and its continual appearance on television screens across the nation in her Message to the Public, 1) a Spectacolor lightboard project supported through the Public Art Fund, in which she eo-opted a large digital screen in the centre of Times Square. Throughout the day this site, normally the privileged domain of advertising, displayed digital text that announced the inanity of war and its attachment to the male ego. WARS HAPPEN WHEN THE MEN WHO LEAD THE NATIONS OF THE WORLD GET THEIR EGOS BRUISED it declared. WE ARE ALL BEING HELD HOSTAGE BY A BUNCH OF GREEDY GUYS WHO ARE WORRIED ABOUT THE SIZE OF THEIR WEAPONS: WORRIED ABOUT THEIR MANHOOD. Twenty years on to the day and the world has come full circle. “I make no grand which in her work become memories of the past dictated claims for my work,” Barbara remarks, “but the issues that through the power of the stereotype. I tend to avoid imagery appear in my photo-text pieces of the early 1980s are that is too immediately recognisable as it tends to periodise horrifically repeated again and again, especially after 9/11. The choreographies of power and control continue to inform should signal a thought or feeling as opposed to rooting that our lives in ever more insidious and manipulative ways. Money and power do not go out of style.”

Indeed the work of Barbara Kruger throughout the 1980s and 1990s has examined the mechanisms of power as it is played out through the mediated language of image culture. 2) Who is bought and sold? she asks in a series of work from 1987. 3) Who is beyond the law? Utilising a form of direct address or “economy of the overture”, a form of confrontational language prevalent in advertising that positions the reader as both active participant and passive subject, such photo-text works explore the means by which stereotypes infiltrate our daily lives. “I learned to deal with an economy of the image and text which beckoned and fixed the spectator,” Barbara explained in the late 80s. “I learned to think about a kind of quickened effectivity, an accelerated seeing and reading which reaches a near apotheosis in television.” Works such as 4) We have received orders not to move or 5) Memory is your image of perfection, both from 1982, display a combination of image and text that simultaneously challenges and subjugates the spectator. The images portrayed in these works allude to the positioning of the female subject within the discourse of a patriarchal culture. The former features the silhouette of a woman pinned to a board like some kind of insect specimen while the latter, an x-ray image of a skeleton complete with feminine accoutrements and high-heeled shoes, reflects the female subject as seen through the penetrating glare of the male gaze. The images used in these works, and in the majority of Barbara Kruger’s work to date, are appropriated from old photographic look books or how-to manuals from the 50s which she crops and modifies according to her needs. By incorporating a memory of the past in the form of imagery selected from America’s golden decade, Barbara effectively alludes to the collective unconscious of the media or what Freud may have referred to as “screen memories” which in her work become memories of the past dictated through the power of the stereotype. “I tend to avoid imagery that is too immediately recognisable as it tends to periodise the work and so limit meaning,” Barbara comments. “Rather it should signal a thought or feeling into an immediate or identifiable present.”

“The early to mid 1970s was an interesting time. It was an economic depression that sparked a creative outpouring of ideas. When the economy is bad people tend to gravitate towards film, video and installation work. At that time it seemed as if everyone was in a rock band” – Barbara Kruger

Barbara’s expertise in manipulating images and text stems back to her time working as a graphic designer and picture editor for Condé Nast. Having spent a year studying under Diane Arbus and Marvin Israel at the Parson’s School of Design to pursue a career in magazines, becoming at the tender age of 22 the head designer at the Condé Nast title Mademoiselle in 1968. What followed was an 11 year apprenticeship in image design that culminated in her appointment as the picture editor for House & Garden in the mid 1970s. At the same time as she was working full time and then freelance at Condé Nast, Barbara also pursued her own interests as an artist and graphic designer. In the 1970s she designed covers for a number of anarchist and left wing books and attended the regular gatherings of Artist’s Meeting for Cultural Change, a think tank that met at a prominent “alternative” gallery called the Artists Space, situated in Soho off Greene Street and Houston. lt was here that she experimented with writing and staging poetry readings after witnessing Patti Smith the male gaze. The images used in these works, and in the majority of Barbara Kruger’s work to date, are appropriated from old photographic look books or how-to manuals from the 50s which she crops and modifies according to her needs. By incorporating a memory of the past in the form of imagery selected from America’s golden decade, Barbara perform at Saint Mark’s Church in the late 1960s. She also exhibited her first artworks in the form of crocheted and sewn hangings adorned with paint, glitter and ribbons integrating so-called “women’s work” into the language of art. “The early to mid 1970s was an interesting time,” she recalls. “It was an economic depression that sparked a creative outpouring of ideas. When the economy is bad people tend to gravitate towards film, video and installation work. At that time it seemed as if everyone was in a rock band.”

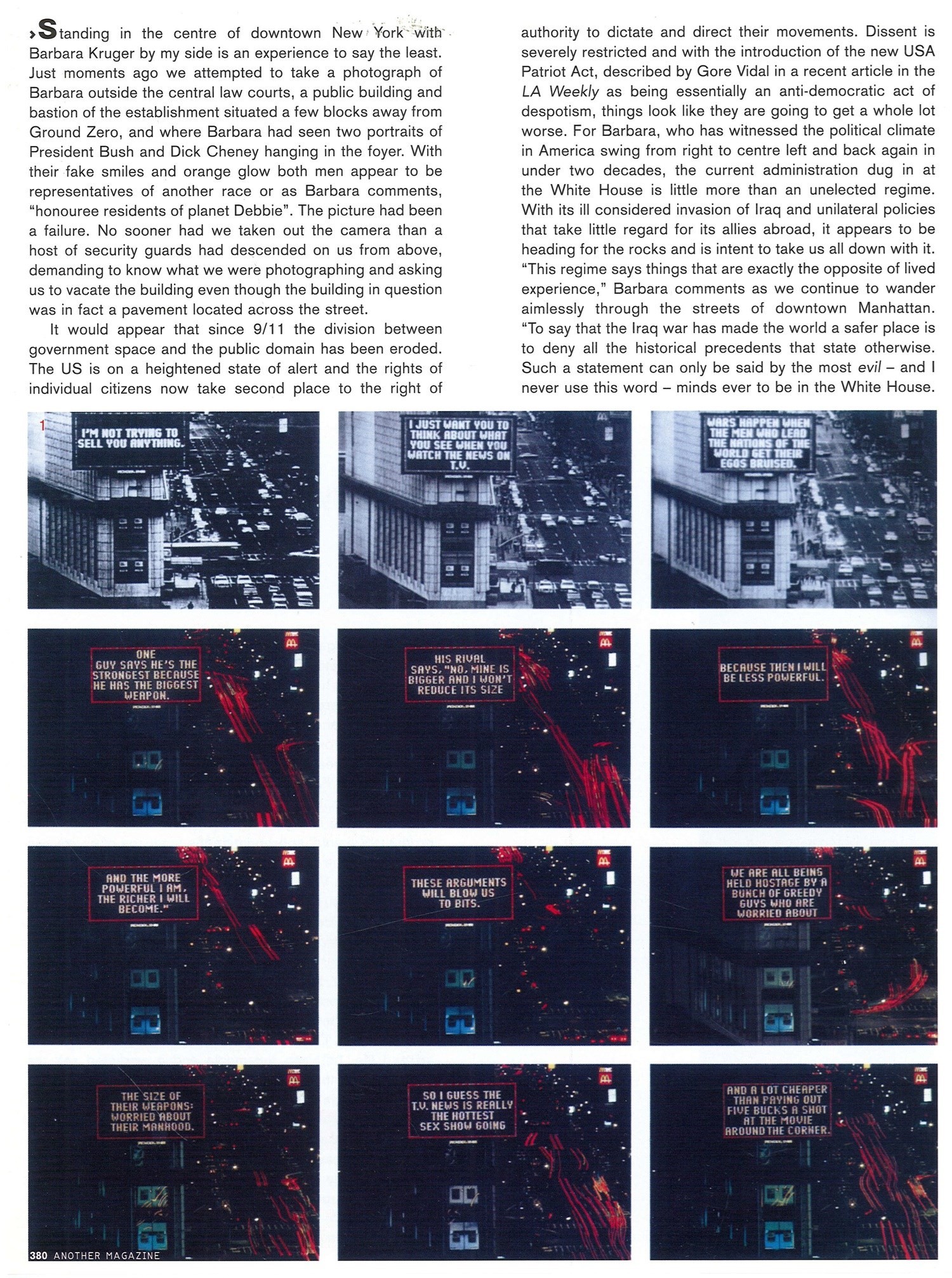

At the same time as experimenting with art and poetry, Barbara also began to discover the writings of Waiter Benjamin and Roland Barthes. It was through her private studies of their books such as Benjamin’s Reflections and Barthes’ A Lover’s Discourse, that she began to formulate an understanding of the world in terms of the hidden power relations embedded within it. lt was Roland Barthes in particular that provided the theoretical tools needed to decode the prevalent signifiers circulating throughout culture. “Language,” he declared, “is legislation, speech is code ... To utter discourse is not, as is too often repeated, to communicate; it is to subjugate.” Barthes’ unravelling of the codes contained within language also led him to consider the semiotic field of the image. “The rhetoric of the image” as he described it, was not an innocent arena but rather a loaded discourse just like any other, capable of positioning and subjugating its subject. For Barbara the post-modern self became a decentred entity, a fragmented self whose identity was constructed through representation. As a female artist working in the predominantly male art world of the late 1970s, the question of female identity and its construction , and manipulation through a patriarchal discourse, became the primary site of investigation. “I was concerned with the way our conception of the self is all too often mediated through other channels,” she explains. “The ideal of the self therefore becomes but a construct, a combination of multiple, fragmented images and discourses that inform and control our everyday lives.”

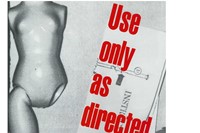

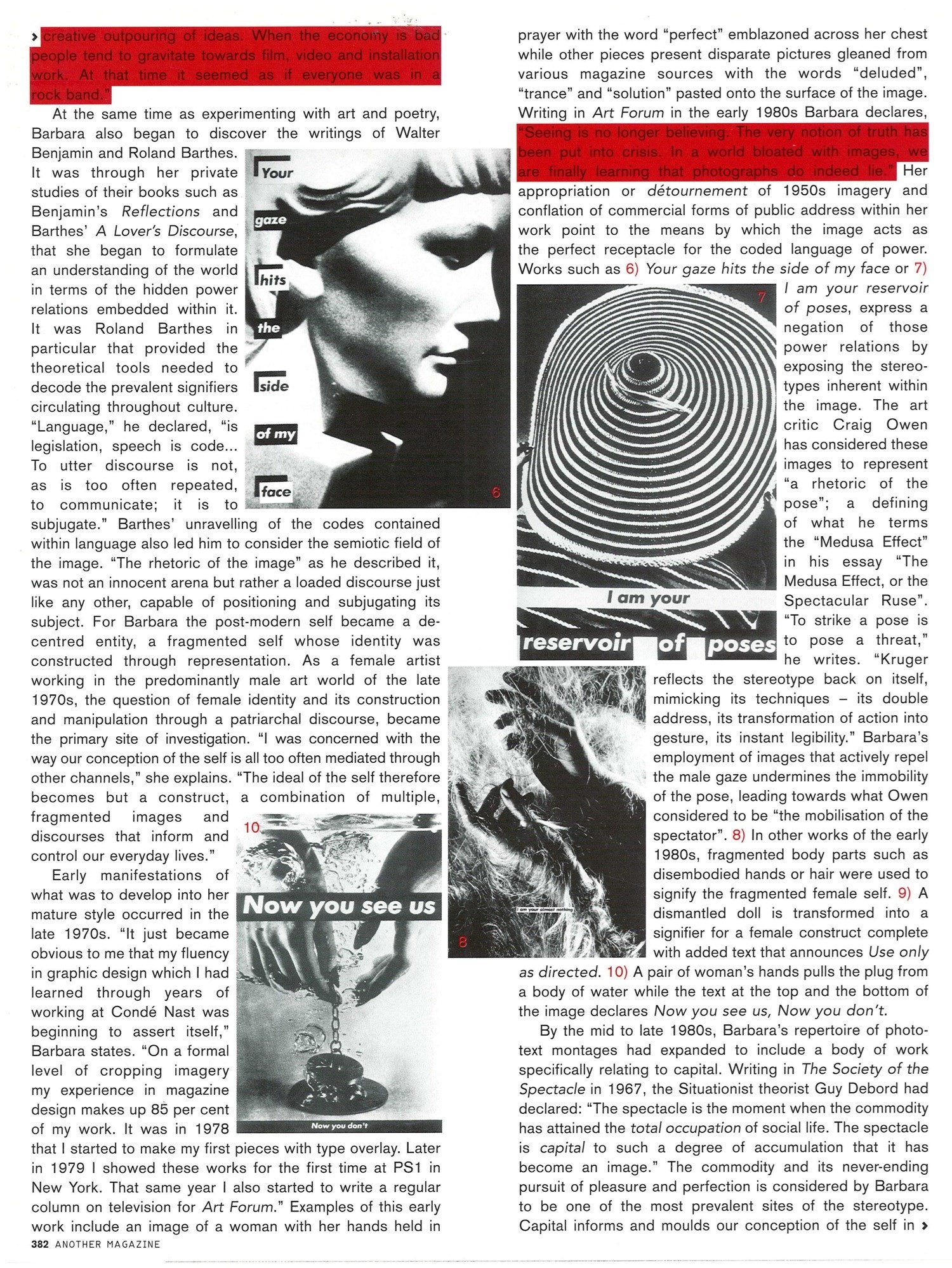

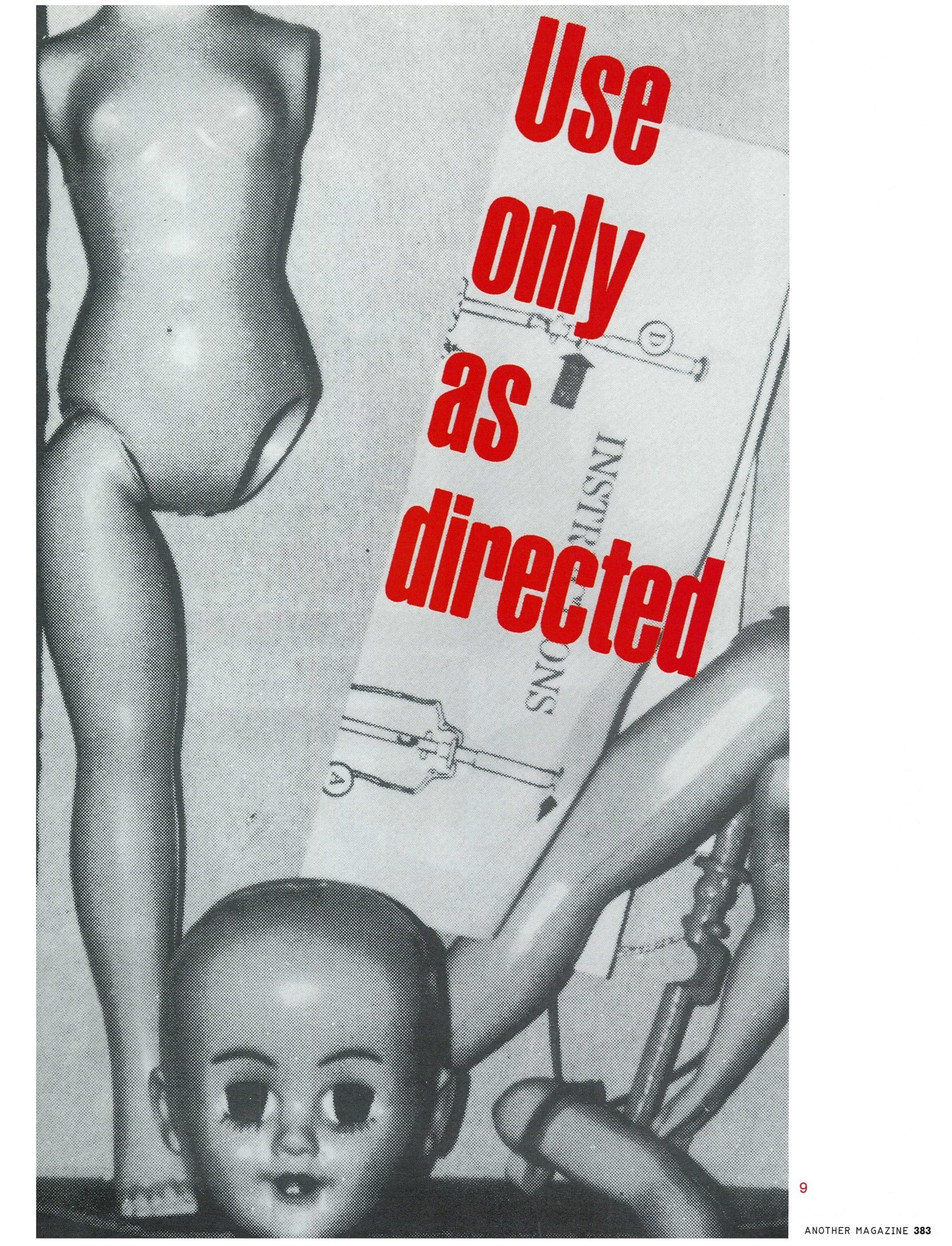

Early manifestations of what was to develop into her mature style occurred in the late 1970s. “lt just became obvious to me that my fluency in graphic design which I had learned through years of working at Conde Nast was beginning to assert itself,” Barbara states. “On a formal level of cropping imagery my experience in magazine design makes up 85 per cent of my work. lt was in 1978 that I started to make my first pieces with type overlay. Later in 1979 I showed these works for the first time at PS 1 in New York. That same year I also started to write a regular column on television for Art Forum.” Examples of this early work include an image of a woman with her hands held in prayer with the word “perfect” emblazoned across her chest while other pieces present disparate pictures gleaned from various magazine sources with the words “deluded”, “trance” and “solution” pasted onto the surface of the image. Writing in Art Forum in the early 1980s Barbara declares, “Seeing is no longer believing. The very notion of truth has been put into crisis. In a world bloated with images, we are finally learning that photographs do indeed lie.” Her appropriation or détournement of 1950s imagery and conflation of commercial forms of public address within her work point to the means by which the image acts the perfect receptacle for the coded language of power. Works such as 6) Your gaze hits the side of my face or 7) I am your reservoir of poses, express a negation of those power relations by exposing the stereotypes inherent within the image. The art critic Craig Owen has considered these images to represent “a rhetoric of the pose”; a defining of what he terms the “Medusa Effect” in his essay “The Medusa Effect, or the Spectacular Ruse”. “To strike a pose is to pose a threat,” he writes. “Kruger stereotype back on itself, mimicking its techniques - its double address, its transformation of action into gesture, its instant legibility.” Barbara’s employment of images that actively repel the male gaze undermines the immobility of the pose, leading towards what Owen considered to be “the mobilisation of the spectator”. 8) In other works of the early 1980s, fragmented body parts such as disembodied hands or hair were used to signify the fragmented female self. 9) A dismantled doll is transformed into a signifier for a female construct complete with added text that announces Use only as directed. 10) A pair of woman’s hands pulls the plug from a body of water while the text at the top and the bottom of the image declares Now you see us, Now you don’t.

“Seeing is no longer believing. The very notion of truth has been put into crisis. In a world bloated with images, we are finally learning that photographs do indeed lie”

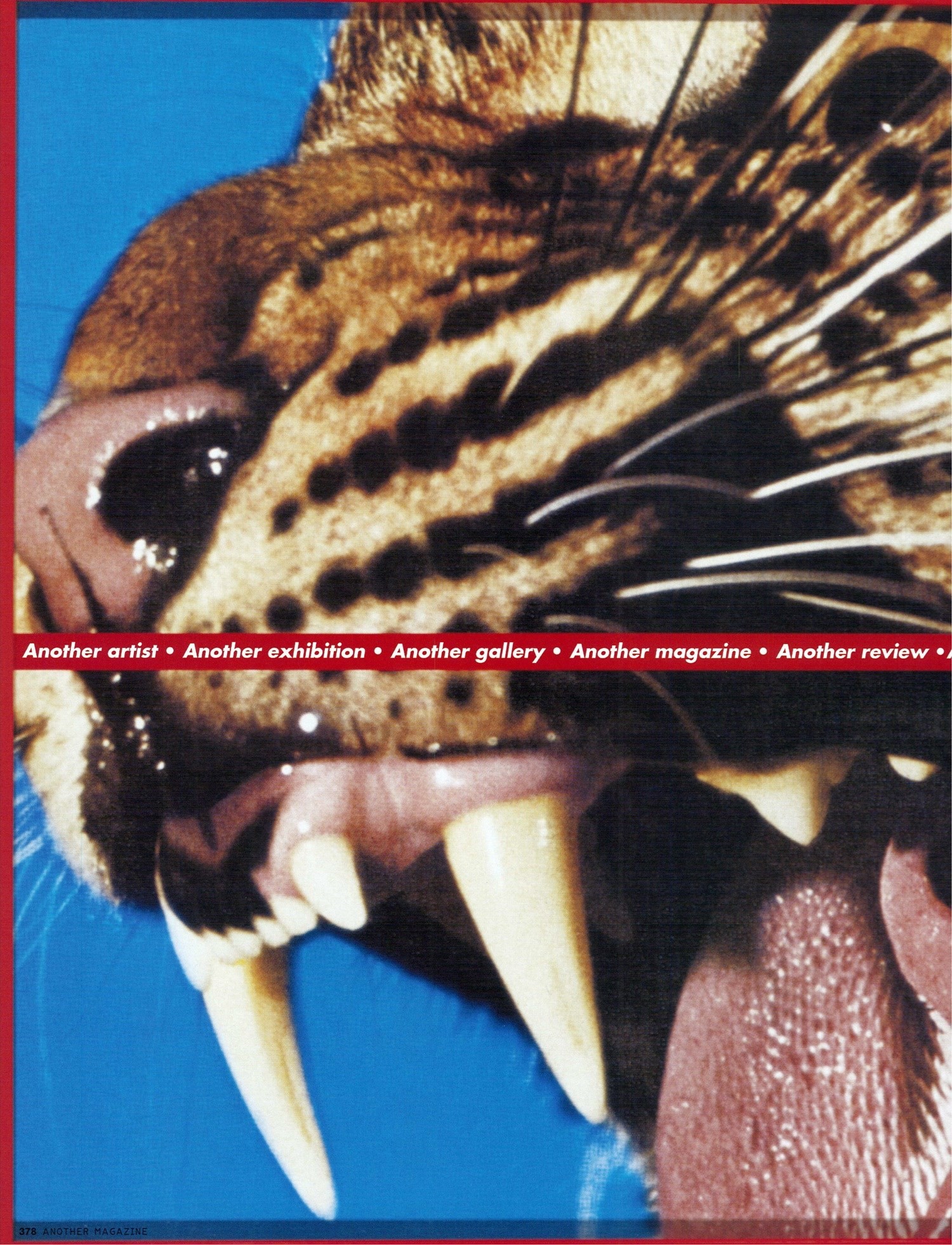

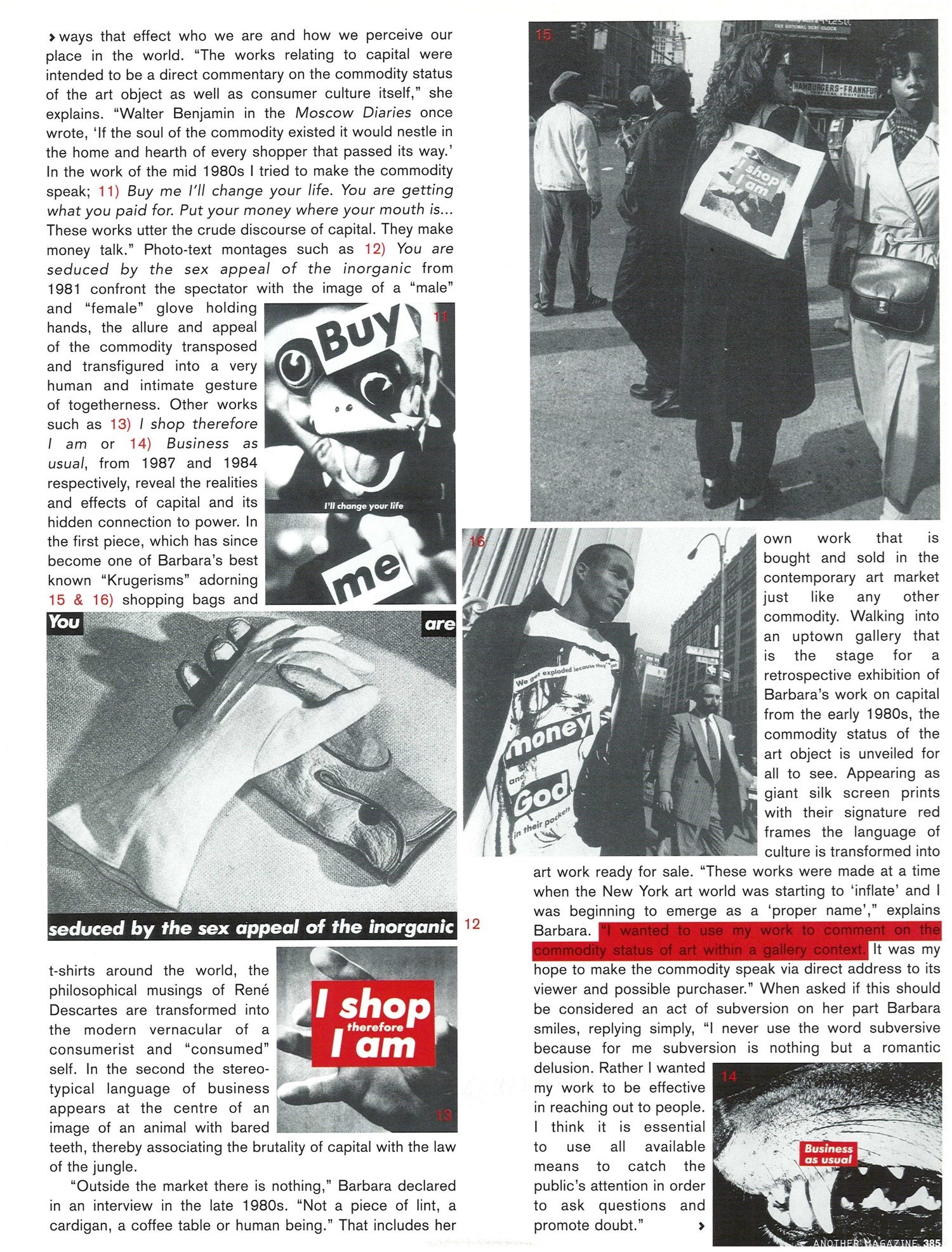

By the mid to late 1980s, Barbara’s repertoire of phototext montages had expanded to include a body of work specifically relating to capital. Writing in The Society of the Spectacle in 1967, the Situation ist theorist Guy Debord had declared: “The spectacle is the moment when the commodity has attained the total occupation of social life. The spectacle is capital to such a degree of accumulation that it has become an image.” The commodity and its never-ending pursuit of pleasure and perfection is considered by Barbara to be one of the most prevalent sites of the stereotype. Capital informs and moulds our conception of the self in ways that effect who we are and how we perceive our place in the world. “The works relating to capital were intended to be a direct commentary on the commodity status of the art object as well as consumer culture itself,” she explains. “Waiter Benjamin in the Moscow Diaries once wrote, ‘If the soul of the commodity existed it would nestle in the home and hearth of every shopper that passed its way.’ In the work of the mid 1980s I tried to make the commodity speak; 11) Buy me I’ll change your life. You are getting what you paid for. Put your money where your mouth is ... These works utter the crude discourse of capital. They make money talk.” Photo-text montages such as 12) You are seduced by the sex appeal of the inorganic from 1981 confront the spectator with the image of a “male” and and "female" glove holding hands, the allure and appeal of the commodity transposed and transfigured into a very human and intimate gesture of togetherness. Other works such as 13) I shop therefore I am or 14) Business as usual, from 1987 and 1984 respectively, reveal the realities and effects of capital and its hidden connection to power. In the first piece, which has since become one of Barbara’s best known “Krugerisms” adorning 15 & 16) shopping bags and t-shirts around the world, the philosophical musings of René Descartes are transformed into the modern vernacular of a consumerist and “consumed” self. In the second the stereotypical language of business appears at the centre of an image of an animal with bared teeth, thereby associating the brutality of capital with the law of the jungle.

“Outside the market there is nothing,” Barbara declared in an interview in the late 1980s. “Not a piece of lint, a cardigan, a coffee table or human being.” That includes her own work that is bought and sold in the contemporary art market just like any other commodity. Walking into an uptown gallery that is the stage for a retrospective exhibition of Barbara’s work on capital from the early 1980s, the commodity status of the art object is unveiled for all to see. Appearing as giant silk screen prints with their signature red frames the language of culture is transformed into art work ready for sale. “These works were made at a time when the New York art world was starting to ‘inflate’ and I was beginning to emerge as a ‘proper name’,” explains Barbara. “I wanted to use my work to comment on the commodity status of art within a gallery context. It was my hope to make the commodity speak via direct address to its viewer and possible purchaser.” When asked if this should be considered an act of subversion on her part Barbara smiles, replying simply, “I never use the word subversive because for me subversion is nothing but a romantic delusion. Rather I wanted my work to be effective in reaching out to people. I think it is essential to use all available means to catch the public’s attention in order to ask questions and promote doubt.”

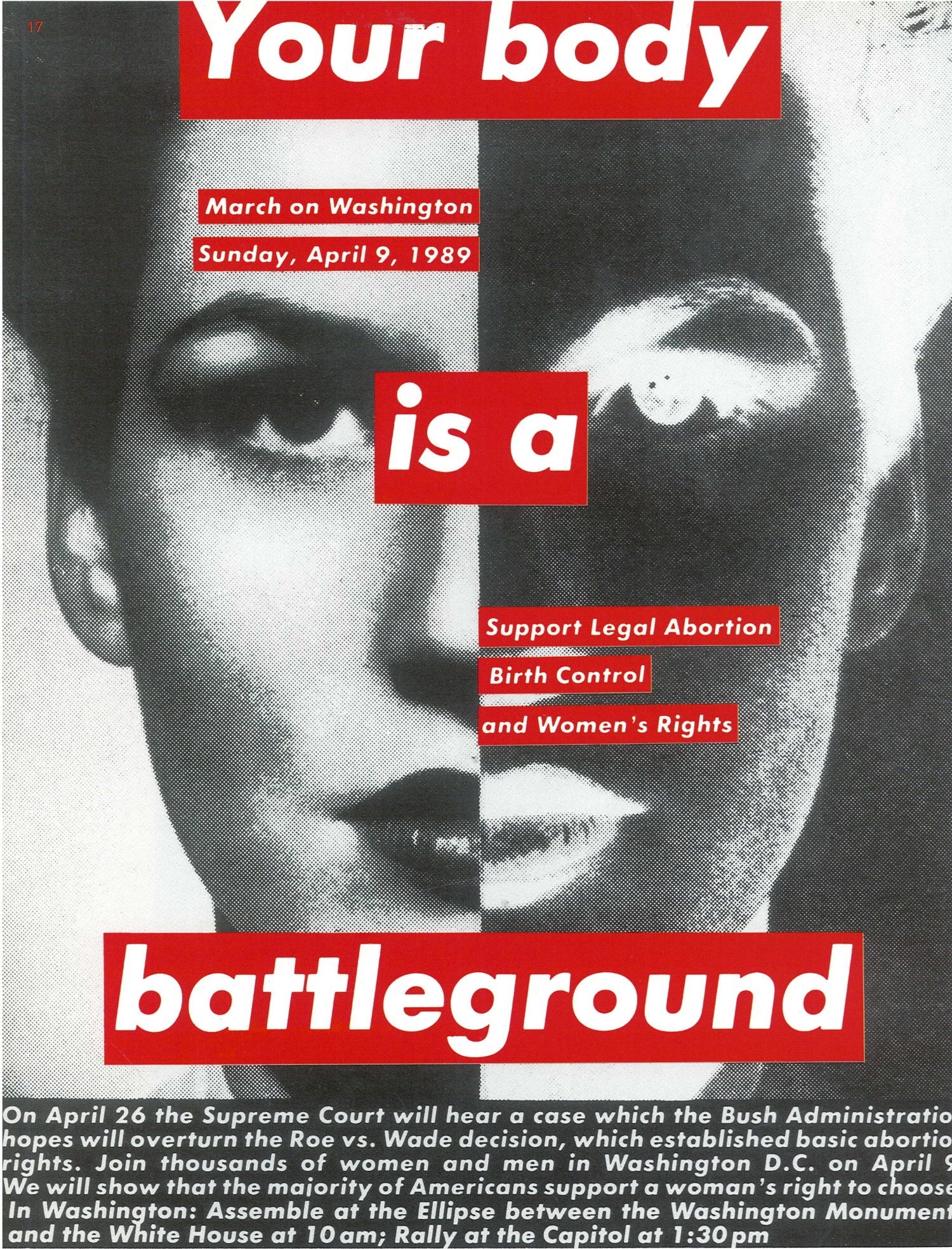

These are no idle words. Over the past two decades Barbara Kruger has revolutionised how we see and read her work not only within the format of the gallery but also in the very public domain of the street. Her work has been transformed into posters supporting everything from women’s rights to abortion with the slogan Your body is a battleground to the campaign for a living wage with the text 17). It’s a small world but not if you have to clean it. Men’s public urinals, bus shelters and even buses have been eo-opted to bring the word back into the street. 18) “Give your brain as much attention as you do your hair,” announces Malcolm X, his words scrawled along the side of a New York bus “and you will be a thousand times better off.” For Barbara such direct provocation targeted at the casual passer-by is not intended to be read as a sermon. Preaching is the furthest thing from her mind. “The important thing for me is that I always include myself in my work,” she insists. “I live and breathe the same culture as everyone else and I am party to the same codes of seduction. I never consider myself to be the grand commentator, the one with the answers, the ‘moral’ one. I’m more interested in questioning the surety of knowledge and a conception of ‘morality’ that has become the alibi for so much unrelenting terror and abuse in this world.” That is, Barbara’s eo-option of public sites as platforms for declaration is the means by which she may expand the scope and prevalence of her work to reach out to a broader audience.

“I wanted to use my work to comment on the commodity status of art within a gallery context” – Barbara Kruger

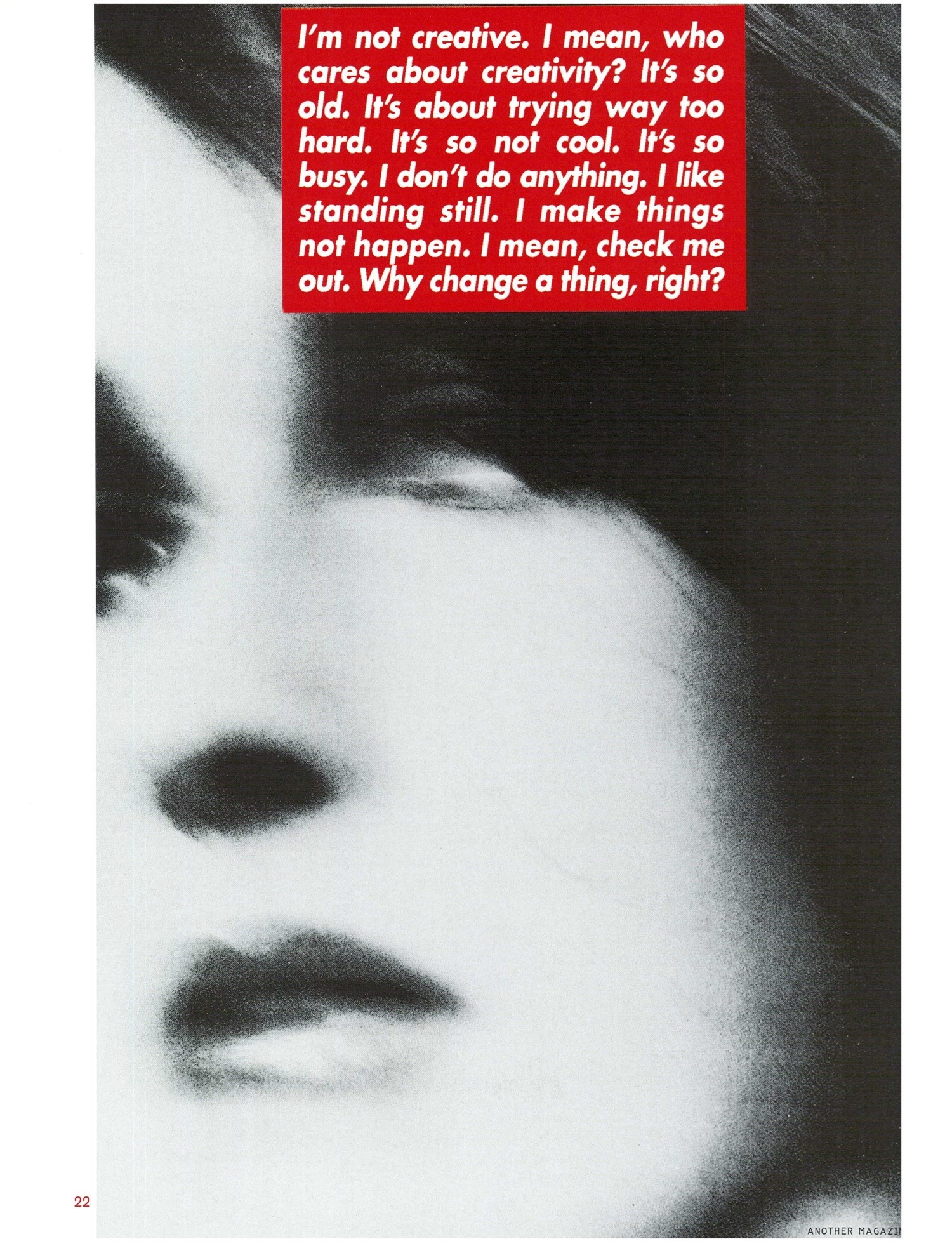

lt is for this reason that Barbara will often display her photo-text montages without any reference back to herself as their creator. 19) The many billboards that have since 1987 been eo-opted as sites for her work in major cities all over the world are often devoid of her “signature” and so remain anonymous. 20) Advertising hoardings such as We don’t need another hero or Don’t be a jerk speak directly to an audience outside of the immediate confines of the art world. As such they confront the spectator instantly, bypassing the limitations and perceived elitism of art. In the same way, Barbara’s co-option of magazines represents another way to confront and challenge mass audiences. 21) In 1992 she completed the cover design for Newsweek, presenting a close cropped image of a man’s distraught face partially covered with text that openly heralded the question Whose Values? and in 1996, 22) in the pages of British style magazine Dazed & Confused she appropriated the trite and hackneyed language of a fashion fanzine, reflecting fashion’s obsession with the image back upon itself. All these strategies are intended to interfere with the channels of communication that have become a conduit for the intimate and persuasive mechanisms of power. Of all these channels television remains the most potent. “The footprint that television has left on American culture is immeasurable,” Barbara declares. “We live in the age of the soundbite where the attention span of the average viewer is forever shrinking. I want to engage that attention span and allow my work to speak out to audiences that remain secluded from the privileged terrain of the art world. I want my work to circumnavigate the proscribed limits of introspective art.”

God said it. I believe it. And that settles it. 23) So states Barbara Kruger in a work produced in 1987, an ironic take on the kind of language often used by the new right in America. After leaving New York we find ourselves at Barbara’s house in Los Angeles, a beautiful yet by no means extravagant escape pad high in the Hollywood Hills, which has been her second home for over 20 years. The decor is minimal with a subtle use of grey and green throughout. In the bathroom next to the toilet rests a solitary copy of Pierre Bourdieu’s On Television and Journalism, an interesting account on the dumbing down of the news media, although according to Barbara not without its own limitations. A self-confessed consumer of media in all its multifarious forms, television represents for Barbara the mirror by which we see our own cultural reflection.

“Television is the perfect vehicle for viewing certain tropes or stereotypes that are so indicative of tendencies that circulate throughout our culture,” she states with a smile. “Recently I watched the final episodes of American Idol, something that we Americans inherited from you British. In the finals there was a queer-bashing Marine whom people felt they had to ‘support’ because the country was off to war. Then there was what seemed like a closet gay guy and a heavy set black soul singer, who eventually went on to win the cbmpetition. The programme was fascinating to watch because each contestant’s image had been tailored to a different market. Each participant was displayed and transformed into a human commodity, only their sell-by dates were all too apparent.”

“The footprint that television has left on American culture is immeasurable. We live in the age of the soundbite where the attention span of the average viewer is forever shrinking” – Barbara Kruger

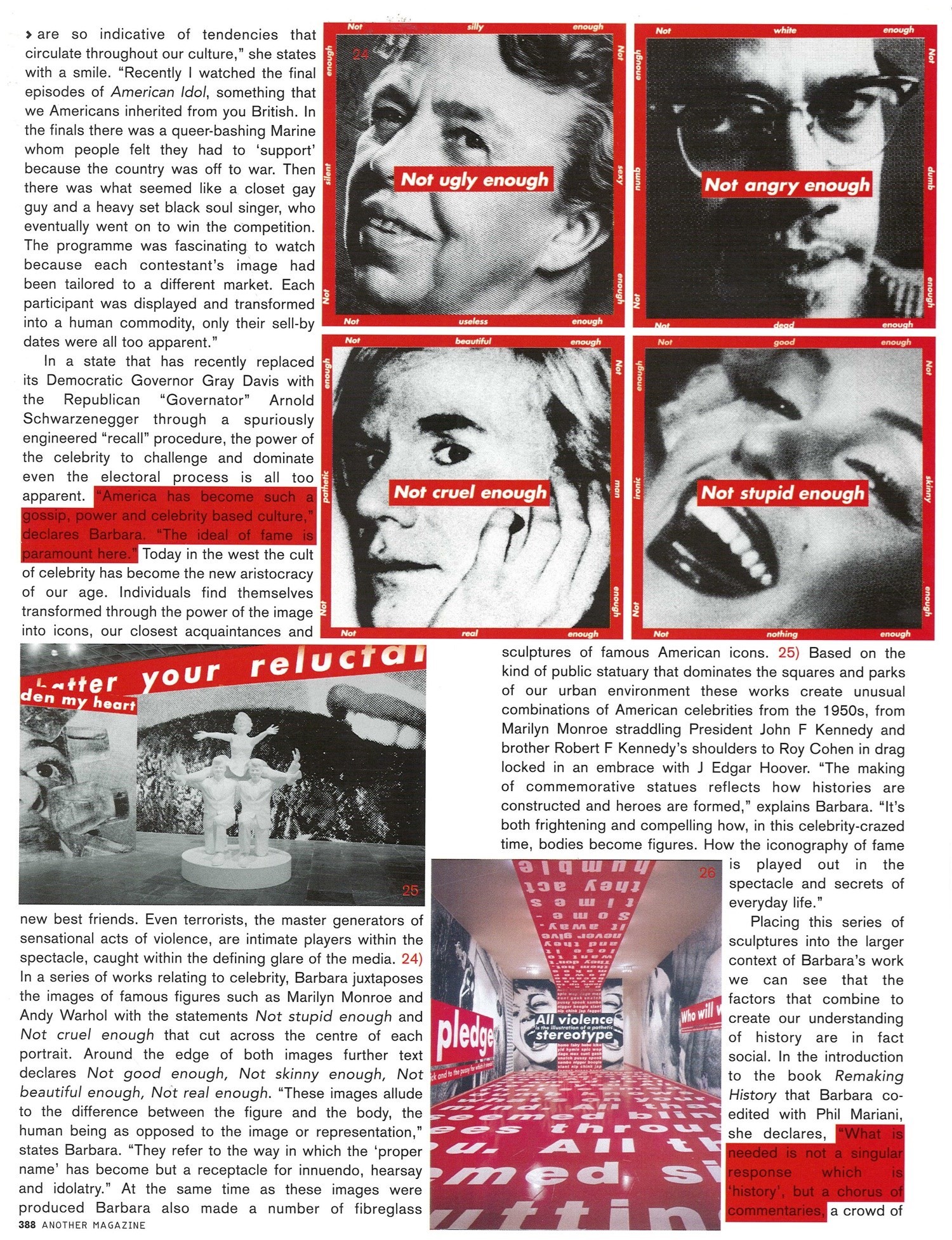

In a state that has recently replaced its Democratic Governor Gray Davis with the Republican “Governator” Arnold Schwarzenegger through a spuriously engineered “recall” procedure, the power of the celebrity to challenge and dominate even the electoral process is all too apparent. “America has become such a gossip, power and celebrity based culture,” declares Barbara. “The ideal of fame is paramount here.” Today in the west the cult of celebrity has become the new aristocracy of our age. Individuals find themselves transformed through the power of the image into icons, our closest acquaintances and new best friends. Even terrorists, the master generators of sensational acts of violence, are intimate players within the spectacle, caught within the defining glare of the media. In a series of works relating to celebrity, Barbara juxtaposes the images of famous figures such as Marilyn Monroe and Andy Warhol with the statements ‘Not stupid enough’ and ‘Not cruel enough’ that cut across the centre of each portrait. Around the edge of both images further text declares ‘Not good enough’, ‘Not skinny enough’, ‘Not beautiful enough’, ‘Not real enough’. “These images allude to the difference between the figure and the body, the human being as opposed to the image or representation,” states Barbara. “They refer to the way in which the ‘proper name’ has become but a receptacle for innuendo, hearsay and idolatry.” At the same time as these images were produced Barbara also made a number of fibreglass sculptures of famous American icons. Based on the kind of public statuary that dominates the squares and parks of our urban environment these works create unusual combinations of American celebrities from the 1950s, from Marilyn Monroe straddling President John F Kennedy and brother Robert F Kennedy's shoulders to Ray Cohen in drag locked in an embrace with J Edgar Hoover. “The making of commemorative statues reflects how histories are constructed and heroes are formed,” explains Barbara. “It’s both frightening and compelling how, in this celebrity-crazed time, bodies become figures. How the iconography of fame is played out in the spectacle and secrets of everyday life.”

Placing this series of sculptures into the larger context of Barbara’s work we can see that the factors that combine to create our understanding of history are in fact social. In the introduction to the book Remaking History that Barbara co-edited with Phil Mariani, she declares, “What is needed is not a singular response which is ‘history’, but a chorus of commentaries, a crowd of reckonings.” In the early to mid 1990s this sentiment was put into practice in a series of installations at the Mary Boone Gallery. Covering every available space including the floor and the ceiling with her trademark white text on red backgrounds, Barbara transformed the pristine white gallery space into a barrage of images and texts that assaulted the spectator from every available angle.’ Who will write the history of tears?’ she asks, the text emblazoned across image of an infant sucking on a bottle of baby’s milk. On the far walls images of two screaming children and a naked woman crucified on a cross wearing a gas mask, declare ‘All violence is the illustration of a pathetic stereotype and it’s our pleasure to disgust you’. On the floor appears multiple texts that render the discourse of power tangible, their visceral and violent address rooting you to the spot. ‘All that seemed beneath you is speaking to you now’ Barbara announces in an installation at the Mary Boone Gallery in 1994. ‘All that seemed deaf hears you. All that seemed dumb knows what’s on your mind. All that seemed blind sees through you. All that seemed silent is putting words right into your mouth.’

In a chapter devoted to torture in her seminal book The Body in Pain, the theorist Elaine Scarry has argued that the torture room is a room transformed into a weapon where the unit of shelter becomes the site for “the disintegration of the world and obliteration of consciousness”. With her combination of brutal images and inflamed text Barbara transforms the usually serene gallery space into a metaphor for the body in pain where the instruments of torture become channelled through the violence of language, both visual and verbal. “When you are in pain the world disappears and all you feel is your body. There is no extension out. There is no external thought. There is no metaphor. There is only the constant introspection of the internal,” she asserts. “When I make a piece that declares ‘Forget heroes, Forget morality, Forget shame’, I am not kidding. We live under a reconstituted notion of a received idea of morality that is a language all too often appropriated by the right. What is good and what is evil? We have to learn to have an understanding of difference. We have to learn to accept the other.”

“America has become such a gossip, power and celebrity based culture,” declares Barbara. “The ideal of fame is paramount here” – Barbara Kruger

“Language is a skin,” declared Roland Barthes in A Lover’s Discourse. “I rub my language against the other. lt is as if I had words instead of fingers, or fingers at the tip of my words.” Walking into a Barbara Kruger installation is like walking into the body politic itself. You enter the lion’s den and witness the stereotype cry out and in doing so render itself visible. ‘Hate like us, Fight like us, Think like us, Fear like us, Look like us, Pray like us …’ The manipulative voice of power echoes throughout the room. In her latest work, which includes video projections of actors reading scripts written by the artist and due to be exhibited in New York next year, Barbara continues her investigation into the more intimate side of the self and its relationship to the codes of power, which she started in 1997 with the text and video installation Power / Pleasure / Desire / Disgust. In that piece the spectator was confronted by text that covered the walls and floor of a temporary space in New York’s SoHo district. The text asked a series of provocative questions such as ‘What are you looking at?’ ‘Why are you here?’ ‘What do you want?’, while at the end of the room three corridors led towards a series of video projections of people’s faces. Each character spoke about their pain and anguish in isolation from the others. The overall sensation of the work was one of seclusion. In the current video installation Barbara plans to reverse this effect. “The work that I am doing now also includes direct address but rather than the characters talking to you they are talking to each other. Four huge images of four people sitting over a table engaged in conversations about their lives, their families, their lovers and their enemies are projected onto each wall of the gallery. Underneath them a continuous series of text will cut across the image in the same style as ‘breaking news’ in CNN broadcasts. The text will act as a commentary on what is being said in the images above, sometimes stamping the moment, sometimes appearing as a free floating element.”

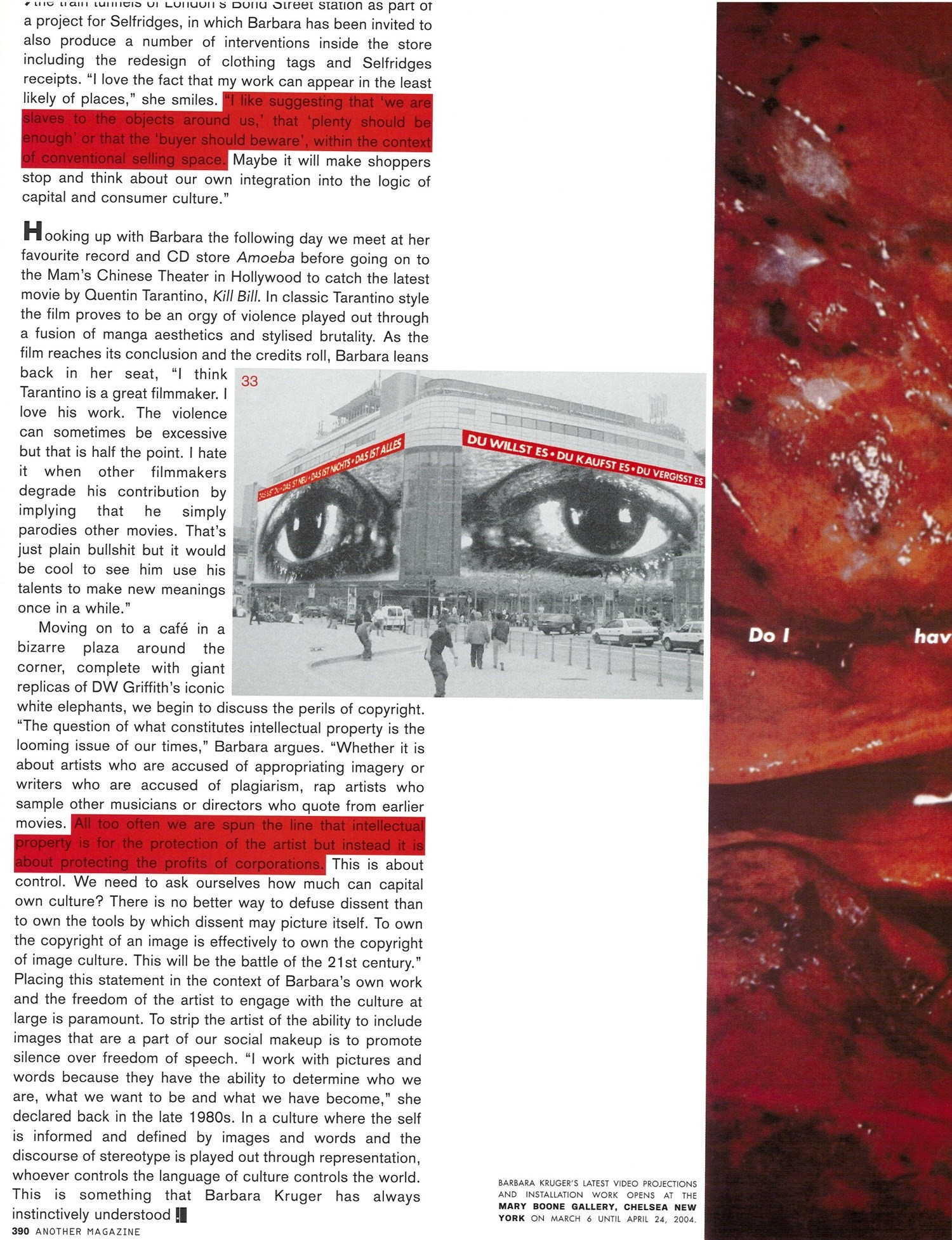

As such, this new body of work has an architectural element attached to it, in which the body of the spectator becomes embroiled in the body of verbal and textual discourse that circulates throughout the room. In the past Barbara has explored the ability of architecture to position us within a social and political space. Her completion of Imperfect Utopia with the architects Smith-Miller and Hawkinson in 1996, a giant permanent outdoor installation at the North Carolina Museum of Art, is an impressive example of how her work may function as architecture. Other examples include her co-opting of the south wall of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles in 1989 or more recently the exterior walls of the Kaufhof Department Store in Frankfurt which she used as the site for two enormous eyes and the slogan ‘You want it, You buy it, You forget it’. Plans are also afoot to co-opt the train tunnels of London’s Bond Street station, as part of a project for Selfridges, in which Barbara has been invited to also produce a number of interventions inside the store including the redesign of clothing tags and Selfridges receipts. “I love the fact that my work can appear in the least likely of places,” she smiles. “I like suggesting that ‘we are slaves to the objects around us,’ that plenty should be enough’ or that ‘the buyer should beware’, within the context of a conventional shopping space. Maybe it will make shoppers stop and think about our own integration into the logic of capital and consumer culture.”

Hooking up with Barbara the following day we meet at her favourite record and CD store Amoeba before going on to the Mam’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood to catch the latest movie by Ouentin Tarantino, Kill Bill. In classic Tarantino style the film proves to be an orgy of violence played out through a fusion of manga aesthetics and stylised brutality. As the film reaches its conclusion and the credits roll , Barbara leans back in her seat, “I think Tarantino is a great filmmaker. I love his work. The violence can sometimes be excessive but that is half the point. I hate it when other filmmakers degrade his contribution by implying that he simply parodies other movies. That’s just plain bullshit but it would be cool to see him use his talents to make new meanings once in a while.”

Moving on to a cafe in a bizarre plaza around the corner, complete with giant replicas of DW Griffith’s iconic white elephants, we begin to discuss the perils of copyright. “The question of what constitutes intellectual property is the looming issue of our times,” Barbara argues. “Whether it is about artists who are accused of appropriating imagery or writers who are accused of plagiarism, rap artists who sample other musicians or directors who quote from earlier movies. All too often we are spun the line that intellectual property is for the protection of the artist but instead it is about protecting the profits of corporations. This is about control. We need to ask ourselves how much can capital own culture? There is no better way to defuse dissent than to own the tools by which dissent may picture itself. To own the copyright of an image is effectively to own the copyright of image culture. This will be the battle of the 21st century.” Placing this statement in the context of Barbara’s own work and the freedom of the art ist to engage with the culture at large is paramount. To strip the artist of the ability to include images that are a part of our social makeup is to promote silence over freedom of speech. “I work with pictures and words because they have the ability to determine who we are, what we want to be and what we have become,” she declared back in the late 1980s. In a culture where the self is informed and defined by images and words and the discourse of stereotype is played out through representation, whoever controls the language of culture controls the world. This is something that Barbara Kruger has always instinctively understood.

This article originally appeared in AnOther Magazine Spring/Summer 2004.