We speak to a photographer who broke boundaries with her fashion and reportage photography in the 20th century

The first photograph Marilyn Stafford took was of Albert Einstein in 1948. The then-23-year-old had owned cameras in her youth in Depression-era Cleveland, Ohio – a Brownie box and later a Rolleiflex – and recalls being impressed with Dorothea Lange’s photographs of migrants that she saw in LIFE magazine. But when Stafford was handed a 35 millimetre camera by friends who were making a documentary on Einstein and “told I would be the stills lady”, she had no professional photography experience.

Stafford’s photograph of the physicist is on show now as part of an exhibition of her portraits in London, Silent Echoes, one of a trio of recent retrospectives on her astounding career. Serendipitous moments like the impromptu shoot with Einstein would continue to pull Stafford back to photography; at the time she was living in New York trying to be an actress – having had theatre training as a child in Cleveland alongside Paul Newman – and then moved to Paris to pursue the same idea. Crossing the channel from Paris to London she met the Indian novelist Mulk Raj Anand, who would become a lifelong friend and the person who introduced Stafford to Henri Cartier-Bresson. “So everything kind of seemed to be moving me towards photography,” Stafford says over the phone. “I know it sounds so weird, but it just seems that the universe was pushing me in that direction. I mean, I would move away from it and I would be sucked back into it.”

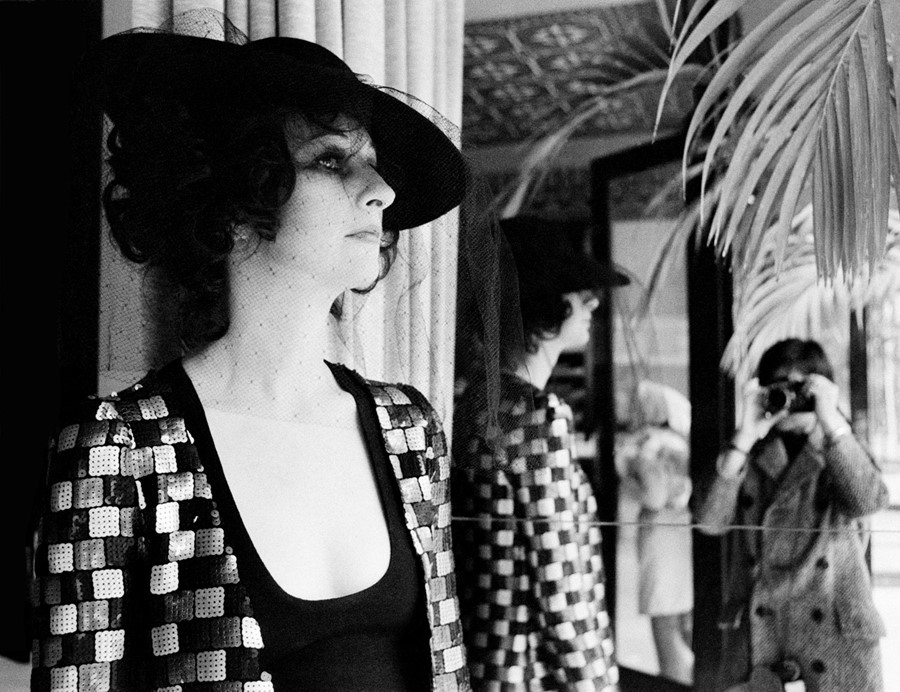

Now a nonagenarian and based in England, Stafford’s career as a photographer began while she lived in Paris in her twenties (where not only was Cartier-Bresson her mentor, but other friends included Édith Piaf, Robert Capa and Bing Crosby), and took her to Algeria, India, Lebanon, the United States and London. Another of the three exhibitions is a look at Stafford’s fashion photography from the 1950s to the 1980s, much of which she created during those years in the French capital and later in London. Stafford had experience of studio photography through working for Francesco Scavullo, “picking up pins”. “At the time he was just more or less starting out, so he was doing catalogue photography, which meant lots and lots of garments that were photographed very quickly,” she remembers.

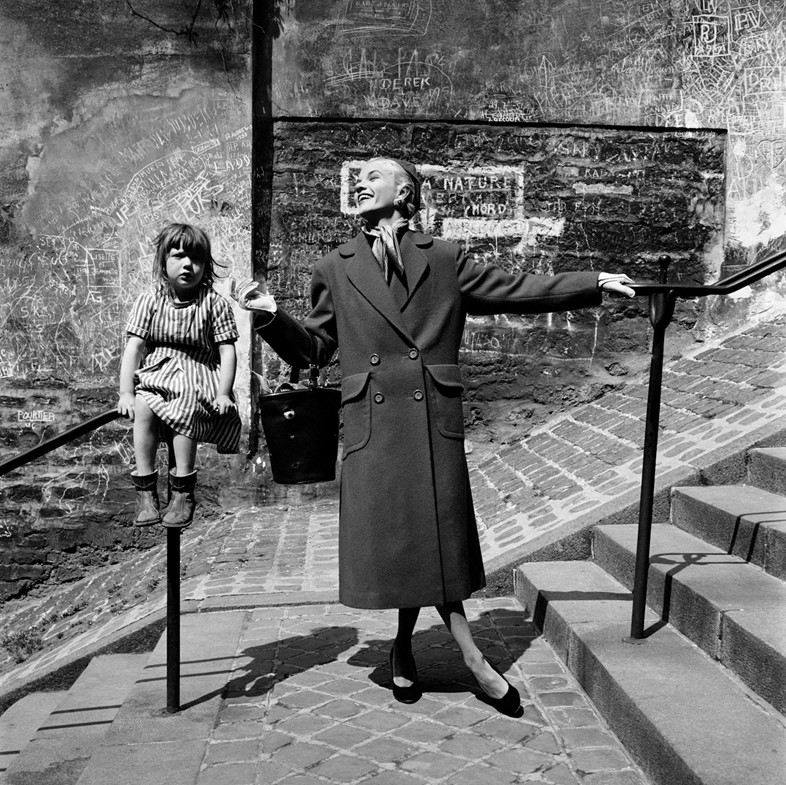

“My job was very multifold... the models would get into clothes that didn’t quite fit them, and they would be all anchored at the back with clothes pegs and straight pins. And of course when the shoot was over the girls would take a deep breath and the pins would go popping around the room and so would the clothes pegs, and you know the lowly assistant was the one who had to clear it all away. I really started at the bottom, and learned quite a lot about the studio work, but I learned also that I wanted to go out into the street and take photographs of people who lived different lives.” And so she did, initially within the realms of fashion photography: Stafford took to the streets of post-war Paris to create imagery for both haute couture houses (Chanel and Christian Dior included) and a burgeoning ready-to-wear industry, and the resulting photographs benefit from the additional characters on the Parisian streets – often children – who engaged with the models and photographer. This defiance of the norm – since fashion photographs were generally created in studios at that time – was a hallmark of Stafford’s career.

The effect of seeing documentary photography in LIFE magazine as a child remained with Stafford during her years in Paris, and her interest in telling people’s stories through image-making led her to document some of the city’s poorest neighbourhoods. “I liked taking pictures of people on the street, and I would get up in the morning get on a bus, go to the end of the line, and just walk about. And that’s how I fell into a very big Paris slum which I took pictures of, which has now been torn down,” she says, referring to the city’s Bastille region. She continues: “I was often invited to go with Cartier-Bresson when he went out shooting, and so I was kind of the little girl with the big Rolleiflex camera, and he was big tall man with a little Leica up to his nose. So people would look at me – and you must remember in the 1950s people didn’t have cameras, it was still poor, it was after the war. Women didn’t wander around with a camera. So in a sense I would take people’s eyes off of him.”

Following this same interest in the stories of the marginalised, Stafford’s next series brought her international acclaim, with two of her photographs appearing on the front page of The Observer in March 1958. This time, her subject was the Algerian war. “The French bombed a hospital on the border between Tunisia and France where a lot of refugees were placed, as well as a Red Cross hospital, and it became a big international incident,” she says. “And because I’d always been interested in displaced people and migrants and refugees I went to Tunisia and that’s where I photographed the refugees from the scorched-earth policy that the French had, of bombing them out of their villages.” The powerful photographs depict mothers and children in tents in the Tunisian countryside, and it was Cartier-Bresson who sent them to the English newspaper. “So that I’m really very proud of. I was at the time pregnant, and my daughter eventually, interestingly enough, having been through all of this became a midwife – because the beautiful photograph that I have is of an Algerian mother holding this newborn baby and it’s a very iconic photograph.”

Working until the 1980s, Stafford’s career continued in other countries and cities; in 1970s India she photographed the country’s first female Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, the 1960s saw her spend a year shooting in Lebanon, and she worked in photo reportage on Fleet Street – one of only two women doing that job, she believes. Though no longer practicing photography herself (and recently busy resurrecting her archive of negatives thanks to support from the Arts Council), Stafford uses her unique eye in working with and mentoring the winners of her namesake photography prize. The Marilyn Stafford Fotoreportage Award – which operates with funding from Olympus, whose London gallery Stafford also exhibited in last month – is a platform for professional female photographers to showcase and, if won, to complete a photo essay which documents a contemporary issue. (This year’s winner, Özge Sebzeci, captured Syrian refugee children in Turkey, while one runner up, Mary Turner, looks at the present-day state of former coal mining towns in Northern England).

Alongside Nina Emmett, founder of Fotodocument, Stafford mentors these women during the creation of their series. “I just kind of sit there and gasp and think oh gosh, I never could have taken a picture that good, it’s just wonderful,” she says. “Nina is very good, she just kind of says this spot could be darkened a little or could be cropped a little, or something like that. Nothing too violent, but just something that will egg the photograph on.” While she was certainly outnumbered as a young female professional photographer, Stafford felt supported by unions and some generous male colleagues – it’s this feeling of support that her award now offers to photojournalism’s new generation of women. But is she nostalgic for her days in the field? “You know it takes a lot of energy and I have a different kind of energy now,” she says. “No, I don’t miss it, I think one has to say it’s time for somebody else to do it, and there’s so many out there. So many wonderful women – let them do it.”

Marilyn Stafford, A Fashion Retrospective: From Haute Couture to the Birth of Prêt à Porter is at Lucy Bell Gallery, Sussex, until November 17, 2018.