Klein’s Anthropometries were radical and controversial – as was most of the work he created in his seven-year career

For a 1958 exhibition entitled The Specialisation of Sensibility in the Raw Material State into Stabilised Pictorial Sensibility, The Void – shortened, thankfully, to The Void – Yves Klein exhibited nothing. The French artist had emptied the Parisian gallery’s room, save for a single glass-fronted cabinet, painted it white and invited guests to view his latest masterpiece – guests who, thanks to the imposing blue curtain outside the gallery and cocktails of the same shade served on the opening night, believed the exhibition to be centred on International Klein Blue, the shade that the artist had developed and become known for. Despite the room being indeed void, people queued to see the show, and it became one of Klein’s most notorious artistic stunts.

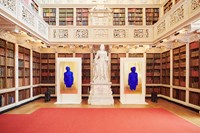

A blue curtain of the same appearance stands at the entrance of Blenheim Palace’s new exhibition on Klein. It may seem at odds to place work by Klein – a man who favoured a subversively complex yet pared-back approach to art – in the stately rooms of Blenheim Palace, the 18th-century ancestral home in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, among classical sculptures, decadent furnishings and Old Masters. The Blenheim Art Foundation’s latest exhibit does just this: Klein’s Monochromes (paintings of a single pigment, rendered in pink, green and predominantly blue) hang alongside portraits by Joshua Reynolds; the myriad objects – globes, Venuses, plates, screens – that he covered in his unbelievably vivid International Klein Blue are placed among ornate gilded furnishings in quiet rooms with ticking grandfather clocks. “We’re not trying to change the meaning of his work but we’re just trying to put it into a different context,” Michael Frahm, director of the Blenheim Art Foundation, tells AnOther.

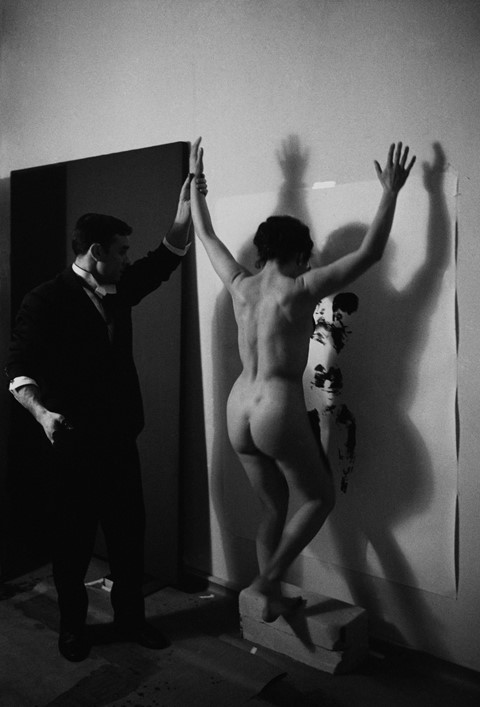

“It’s obviously the first time the works have been shown in this sort of setting so it was an interesting challenge from that perspective,” Frahm continues. “For example the Anthropometry painting which is in the red drawing room – it’s an interesting sort of dialogue, with three Van Dycks there, and you have portraits by Joshua Reynolds and John Singer Sargent. Then you have the 1961 Anthropometry painting, which also deals with the human body and figuration, but with a completely different approach to painting.” The piece that Frahm refers to is one of a series that Klein called the Anthropometries, a practice which would become one of his most infamous, and for which he became renowned. His method was radical and unorthodox: Klein would cover a naked woman (sometimes a few women) in International Klein Blue, and she would put her painted body on the canvas, thus rendering her own figure the paintbrush.

The resulting pieces are swift and vivacious; some full of movement where the model has seemingly writhed around on the canvas (photographs show women almost slapping themselves down and dragging themselves across it) and others portraying just a blue print of the female torso. Daniel Moquay, head of the Yves Klein Estate, comments that “you have the feeling that you have a mud fight” on looking at the Anthropometries. Klein’s ‘living brushes’ were something of a spectacle, and the artist would introduce a performativity to the piece by staging events set to music of his own composition (‘music’ being a loose term: the piece that accompanied these events was made up of a single chord played for 20 minutes, followed by 20 minutes of silence – a conceptual artwork in itself) where people could watch an Anthropometry being created before them.

A radical exploration of the female form, the paintings and performances made headlines at the time and marked a turning point in contemporary art. Klein would direct the Anthropometries, he the conductor and the models his orchestra. What could be seen as a problematic use of the female form in the place of an artist’s tool was in fact more of a collaboration, Elena Palumbo-Mosca, who modelled for Klein in this series, told Tate in 2013. The women were entrusted with a task by Klein, and their role was crucial to the series.

“He is someone who in the 1950s and 60s changed the course of art, and a lot of the things that we take for granted in contemporary art today started with a seed from Yves Klein,” says Frahm. In many ways, Klein was almost anti-art. He pursued judo as a career until his mid-twenties and achieved a black belt in Japan, becoming a master at the sport. When he settled on art, his work was always challenging: his first public work was an irreverent book of monochromes, a play on a traditional monograph that an established artist might release; in his Zones of Immaterial Pictorial Sensibility he offered clients empty space, which they paid for in gold, and when Klein gave them a receipt it would be burned by the Seine as half the gold payment was thrown into the river; he created over 80 Fire Paintings (one of which is featured in the Blenheim exhibition) over the course of one day at the Gaz de France, using women doused with water and flame retardant to create unburned silhouettes on the otherwise charred canvases; and in his photographs entitled Leap into the Void he appeared to fall from great heights off various Parisian buildings. So central was the idea of performance to his practice that when Klein died at the age of 34 – after only a seven-year career – people believed it to be a publicity stunt.

“From the beginning he was a showman, he was very outspoken, very charismatic and put on a show for people,” says Frahm. “Blenheim is a stage, in a way, for him to perform.” Moquay goes on to say, referring to an instance in Klein’s youth that saw he and two friends divide the Earth between them, that “he wanted to paint the entire world. He would’ve been extremely happy to paint the ocean blue.” One wonders if, had Klein’s career not been cut short, he might have one day exhibited in a space like Blenheim Palace, somehow aligning his radical art with its hallowed halls in the ultimate irreverent act. Two blue relief portraits of Klein’s two closest friends mounted on gold panels flank a marble sculpture of Queen Anne in a particularly grand room of the palace. “Queen Anne is going to be painted in blue very very soon. So come back and she’ll be blue,” jokes Moquay. “No, not really, but we can dream of it.”

Yves Klein at Blenheim Palace runs until October 7, 2018.