Discovered in suitcases after her death, Vivian Maier’s photographs paint an enthralling portrait of a rapidly changing America

The frame is a large square negative, where inky black and white creates stark dichotomies and contrasts that emphasise the vivid forms of a twisted mouth or a ruffled skirt. The camera used is a Rolleiflex, a device that allowed the photographer Vivian Maier to focus on her subjects free from scrutiny, her eye directed downwards as she watched the world and its people without having to meet their gaze.

Born in 1926, Maier was herself an anomaly, a prolific artist who produced an extensive archive only discovered after her death in 2009. Endless self-portraits and street studies were found crammed into suitcase after suitcase in a storage depot in the bay area of Chicago. “She was a very private woman, very mysterious,” says Anne Morin, the curator of the new exhibition Vivian Maier at Bologna’s Palazzo Pallavicini.

A flâneur of New York and Chicago’s city streets, Maier experienced her life through photography, and through her photography we can come to experience, at least in part, her life. Already compared to Robert Frank, Lisette Model, Helen Levitt, and Diane Arbus, this exhibition shows her as a constant witness on the streets of America making the invisible visible, creating a narrative of her own making in rolls of monochrome film.

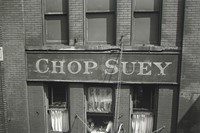

Portraits of distinctive characters abound but what resonates most is Maier’s gaze. “She was interested in seeing how she fit into the world,” says Morin, yet the starkly geometric compositions reveal a curiosity about others too. A man slumped on his hand is framed by piles of neatly stacked newspapers and clipped magazine pages in his kiosk, perfectly centered in Maier’s viewfinder, and perfectly unaware. In another, a sideways glance zooms in through an open window to spy upon the meeting of two men eating together in a restaurant, Chop Suey. Although she travelled extensively, Morin believes her finest work is to be found in these quotidian snapshots: “In her own context of daily life is where her work was strongest. When she was outside her own house, her own territory, in a way she was made distant by the exoticism of the city, the country, the culture.”

Maier created her work for herself, she had no audience. So what are the ethics of exploring the archives of such an apparently private person posthumously? “What’s very clear is that she didn’t put any of her work in the trash. She could have done it,” Morin insists. “She could have destroyed it all, but she left it. She left the door open to someone to find it and do something with her work.” In a way, Morin sees the delayed spotlight on and appreciation of Maier’s work as a blessing in disguise: “She probably would be happy! But she would not be very happy to be doing a press conference. We are giving her a life after death, we’re making a life out of her work.”

Using her Rolleiflex camera meant looking downwards, never making eye contact with her subjects – the twin lens of the camera providing a disguise, or shield, from the world she portrayed. Maier enacted the same liminality in her own working life, both a part of and apart from the wealthy families she served as a nanny. In her photography she practised this ability to be at once engaged and distant, present but invisible. “She said she needed to take a lot of pictures of her face to find her face in the world,” Morin observes. “She was no-one – society had convinced her of that at the time. She was just a nanny, so she took control of her own identity through those self-portraits.” In one striking shot she seems reduced to nothing but a shadow, but on closer inspection stands tall and strong in the miniature reflection of a garden sprinkler embedded within the shadowed grass.

Maier repeatedly solidified her place within the world, with each click of the shutter. “What is really important is that she goes through these very abstract phases, creating representations of herself through the shadow which is now a kind of signature,” notes Morin, “even just in the self-portrait of herself you can really see she was like that, there is always something slightly disturbing in her pictures, or something reflected, a mirror, a light, a shadow – something that is not really clear. There’s always something showing the reflection of her face.” She may have hidden her work, but within Maier is ever-present. Rather than shying away from the camera she confronts it, distorts it, questions it, her archive one long conversation with the camera itself. “From nothing she suddenly became something, and this is what is most important, that she did it through photography. That’s the most important part.”

Vivian Maier runs at Palazzo Pallavicini, Bologna until May 27, 2018.