AnOther speaks to the iconic American artist about her profoundly moving new solo exhibition, Softer

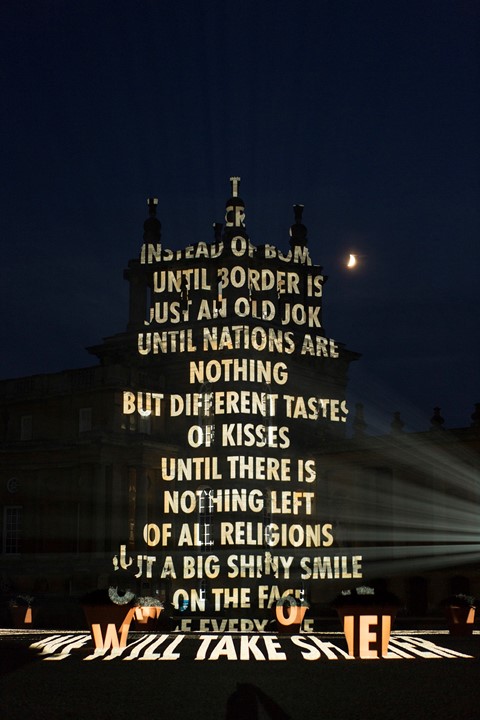

Last Wednesday evening at dusk, Blenheim Palace, the 18th century UNESCO heritage site once home to Sir Winston Churchill, was illuminated with typography that resembled the rolling credits of a Hollywood blockbuster. The outside grounds were drenched, and the light from several giant projectors highlighted the sideways pelting rain. Perhaps it was the adverse weather conditions, or maybe the words emblazoned across the Baroque architecture – excerpts of testimonies from war veterans and Syrian children suffering under Assad’s regime – that made for such a chilling experience. “A baker has a cow. Mother crawls on her stomach among rubble, mud, corpses. She brings back three spoonfuls of milk. The child lives for one more hour,” the text exclaimed, inescapable in its magnitude.

This was the pièce de résistance of Jenny Holzer’s new solo exhibition Softer, showing at the stately home until the end of this year. Titled On War, the projection-based work – the most ambitious the artist has ever realised – forms part of the Blenheim Art Foundation’s 2017 programme, which has, in previous years, invited Ai Weiwei, Lawrence Weiner and Michelangelo Pistoletto to present site-specific work responding to the vast and culturally loaded building. “The palace was imposing,” Holzer says, describing how she first approached the space two years ago. “I thought of doing everything elsewhere – either in the lake or the ancient oak forest – but I gradually found something resembling strength which lead me indoors.”

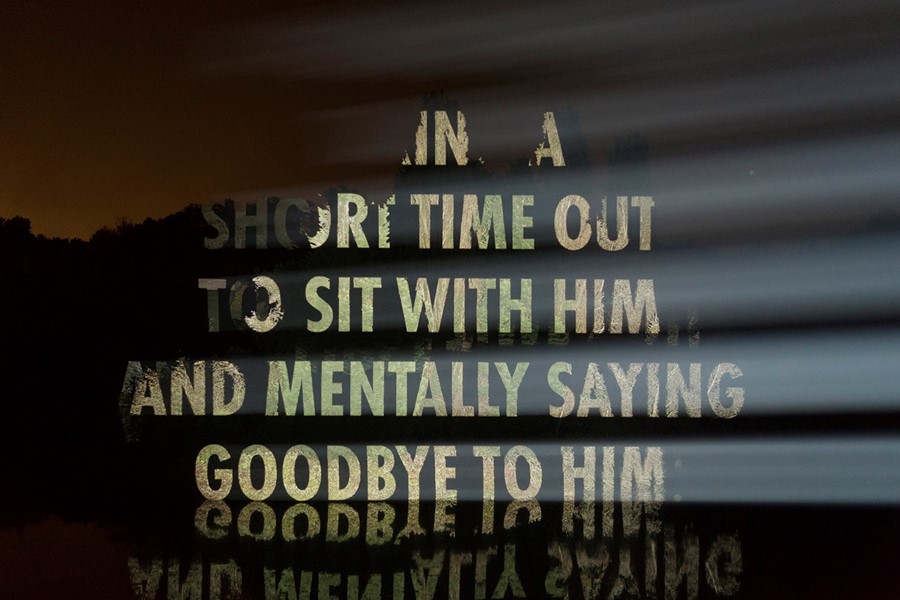

Holzer is renowned for treading the line between the political and the personal, using the provocative medium of language to elicit an emotional response in her art. “Content is key, and language works for conveying meaning – that is why I use it so often,” she says. “I tried to be an abstract painter initially and I was terrible. That is why I started writing. But I do like to convey meaning non-verbally, too.” For Softer, Holzer focused her attention on Blenheim’s military history in relation to the themes explored in her practice since the 1980s: activism, power and conflict. Alongside transcribed accounts of war, elegiac verses came courtesy of Polish poet Anna Świrszczyńska, engraved into marble benches – a staple feature in Holzer’s oeuvre – formed from the same polished stone found in the palace.

“I tried to be an abstract painter initially and I was terrible. That is why I started writing. But I do like to convey meaning non-verbally, too” – Jenny Holzer

Softer, as a whole, represents Jenny Holzer’s unique ability to present work that can be loud and quiet in equal measure. In For Blenheim, an LED fountain spews out letters in acrid blues and reds; in Statement, a hanging bar of light placed in the entrance hall of the building displaying interviews with military detainees, wouldn’t look out of place at a fairground. Yet, some of her sculptural pieces possess a stillness that is just as affecting. “I first used bones in my work right after the war in Yugoslavia, when women and girls were specifically targeted as a tactic,” she says. “I just couldn’t stand it. This was an instance where I couldn’t rely on language alone. I went to the body. At Blenheim, I worked with bones again. I wanted the consequences of war, murder and assault to be seen as real, not neutral.”

The meticulously placed human remains are impactful; a single hip bone lies in a display cabinet amongst the splendour of floral crockery; another case is full to the brim with deconstructed ribcages. Likewise, in Great Table, one of the most sombre pieces on display, Holzer lines up shoulder blades in rows, but they require close scrutiny to be recognised. “I chose to use these bones in particular because they are rather beautiful until you determine what they are. They look a bit like bird wings, sailboats, and other pleasant associations; it provides various meanings simultaneously.”

A surprising element of the exhibition is the smartphone app created by Holzer and a team of developers to offer a virtual component to the show. The artist was one of the first to experiment with the medium of VR back in the early 1990s, and is revisiting it for 2017. “I have wanted to do more with it since the dark ages,” she laughs. “Back then, I met one of the inventors of desktop VR. A woman! It was in the back of my mind when I came here and I saw the on the crest and the sculptures around the palace and particularly the Wyvern on the tomb of the first Duke of Marlborough.” Once the app is downloaded, the digital Wyvern – a mythical dragon, featured on the Marlborough family crest, soars around the vast length of the library. “The dragon is breasty. Like a Louise Bourgeois sculpture,” she says, perhaps in reference to the headless beast with udder-like protrusions that formed part of Bourgeois’ Nature Study series. “It’s my homage to brave creatures.” For any other artist, such an endeavour could be written off as a gimmick – but certainly not for Jenny Holzer. “I want to offer material that is potentially meaningful to people, and I hope that I stop short of any cheap theatrics. I want to offer things that can hurt people, as well as redemptive things.” Softer, in all its profound sincerity, has achieved just that.

Softer runs at Blenheim Palace until December 31, 2017.