As Michelangelo Antonioni's 1967 film capturing London's radical style scene turns 50, we sit down with Blow-Up authority Philippe Garner to deconstruct its inception and influence

The city of London in 1966 was almost theatrical in its duplicity. On the surface, business continued as usual – the dreary post-war years ticking along lethargically. Behind closed doors, however, and to onlookers from the continent, ‘swinging London’ raged; an unprecedented cultural revolution of fashion, parties, sex, drugs and hedonism.

It was this dichotomy which first caught the eye of Michelangelo Antonioni, the Bologna-born film director already well known by that time for his groundbreaking work in Italian cinema; his 1960 film L’Avventura had premiered to a chorus of boos at Cannes Film Festival some six years earlier, marking him out as an inimitable talent, if not an immediately popular one. By ’66, Antonioni’s fascination with the challenge of capturing a mood of doubt and uncertainty had manifested itself in Blow-Up, the now-cult record of London’s dynamic fashion scene. “I think what intrigued Antonioni wasn’t the surface, glamour, excitement or appeal of the new young styles in fashion and music or whatever,” explains Philippe Garner, author of 2010 book Antonioni’s Blow-Up, and formerly Head of Photographs and 20th Century Decorative Arts and Design at prestigious auction house Christie’s. “I think what really intrigued him was the ambiguity of it all. The myth grew very rapidly to be much greater than the reality. It wasn’t that people didn’t listen to certain music, or dress a certain way, but they were all getting revved up and excited around an idea which was no more substantial than the air.”

The resulting film is centred around the character of Thomas, played by David Hemmings – a successful and frustrated fashion photographer who, having made his fortune shooting for magazines, is looking for distraction when one gloomy day he stumbles across a satisfyingly sinister scene while shooting in the park. From up-close, the plot is that of your bread and butter crime drama, set in the midst of a fabulously fraught cultural shift. Seen in context, however, its underpinning themes are much more nuanced, established early on by Antonioni's unique formulae. “I think the first time one sees Blow-Up one is very conscious of visiting this city in an exciting cultural moment,” says Garner, “but the more you actually deconstruct the film, the more you are aware of his probing into the very insubstantial, unsatisfying nature of the collective dream that people were buying into.”

The sense of stasis which pervades the film hammers this point home; long stretches show simple panning shots of Hemming driving through the streets of west London in his Rolls Royce on an overcast day, juxtaposing the glossy novelty of the decade’s legendary parties with the drab reality of life in a conservative city. Grey skies were of paramount importance; rumour has it that a hint of sunshine on the morning of a shoot day would send Antonioni into a furious rage, leaving the cast to play football in a nearby park. His obsession with colour meant that the dreary British weather played an important role in the film, throwing the fashion scenes into sharp technicolour in comparison.

From its pervading atmosphere to the characters themselves, Antonioni’s attention to detail has played a fundamental role in the film’s continuing success. The character of Thomas, for example, is a kind of cut-and-paste amalgam of David Bailey, Terence Donovan and John Cowan – three of the era’s most prolific fashion photographers. Antonioni's research in building Thomas’ character was painstaking; he spent many hours talking to journalists Francis Wyndham and Anthony Haden-Guest to glean detailed references. “He was after a very specific thing: what do they wear, what do they eat, what do music do they listen to, what cars do they drive?” says Garner. “He didn’t want gossip, he wanted to build a picture out of quantifiable details. He watched some at work and he moved in those circles just to observe the way of life of the people living in that fashion scene.”

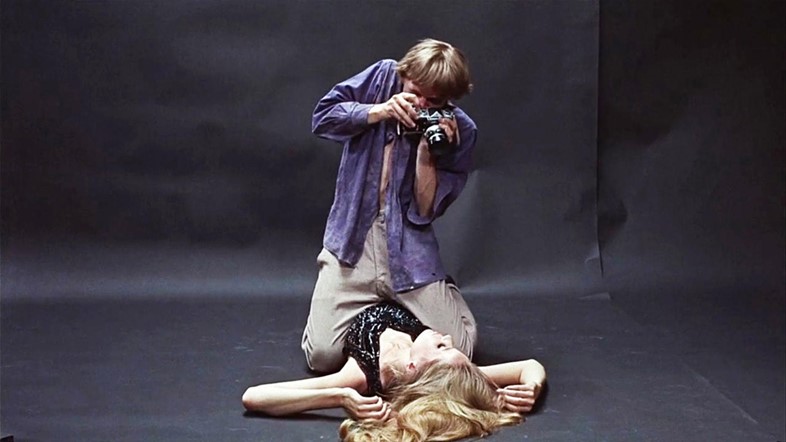

“It was a demonstration of how fashion-related photography had changed in relatively few years – from the sweet era of Cecil Beaton and a certain generation for whom women were very much idols to be placed on pedestals, not to straddle on the floor.” Philippe Garner

Of the many models who star in the film, Jane Birkin, Jill Kennington, Vanessa Redgrave and Veruschka had key roles, the latter playing the photographer's subject in that now-iconic shot of Thomas straddling her on his studio floor, shooting from above. “Veruschka was very much playing herself,” says Garner. “It is an unusual aspect of the film – everyone else is playing a part, and she's being Veruschka! That’s a hell of a scene, very intense, very erotic, very daring for that era, when the censor’s hand was quite strong in keeping films on the straight and narrow. We think of the 60s as being a time of major liberation, but actually I think a great deal more liberation happened in the 70s – the 60s remained very poised in so many respects, so it was very sensual. It was a demonstration of how fashion-related photography had changed in relatively few years, from the sweet era of Cecil Beaton, and a shock certain generation for whom women were very much idols to be placed on pedestals, not to straddle on the floor.”

This fastidious attention to detail extended even to the props used; the documentary photographs Thomas captures of Jane (played by Vanessa Redgrave) in the park were in fact taken by Don McCullin, while the film was largely shot in John Cowan’s studio. “Actually, [Antonioni] was visiting the studio to meet Terry Donovan, who had rented John Cowan’s studio for a shoot for Mary Quant, and that’s how he chanced to be in there. He loved the space, and kind of knew that was where he wanted to shoot the film.”

As for its depiction of the 60s, is the film accurate in its representation, I ask? "Yes, is the simple answer," Garner replies after a moment's hesitation. "I think it is. It tapped into the ambiguity of it – it doesn’t allow itself to be seduced by the fashionable gloss and polish. I think what one needs to remember about that moment in 60s culture is that it was a very small group of people who were making a difference, who were in the news, on television, in the press and in the media, coming to represent this idea of this exciting, expressive city. So yes it was happening, but it was happening for a very select club."

Another Man will host a special anniversary screening of Blow-Up at Second Home's new workspace, which was formerly John Cowan's studio, on September 8, 2016, featuring a Q&A between Philippe Garner and Jill Kennington.