From the tight-laced corsetry of the 20s to the cleavage enhancement of the 90s, we explore the garment that transformed the lives, and silhouettes, of women

Since time imemorial, women have been employing all manner of devices to contort their breasts into whichever silhouette their era determines desirable: from the fascia of ancient Rome to the mastodeton of Crete, the dudou of the Chinese Ming Dynasty to the kanchukas worn in the Indian courts of King Harshavardhana. Whether they were pushing them up (the kanchukas were a kind of preliminary wonderbra) or strapping them down (the fascia was designed to minimise large breasts and mark the genteel's chests apart from the unfettered appendages of slave girls), some version of a brassiere has been a staple throughout the history of dress; there is nothing particularly modern about contraptions designed to do something or other to your chest.

For S/S16, J.W. Anderson took a particular type of vintage-style brassiere – a 30s-esque bi-cup with a shaped underwire and emphasis placed on flattening rather than uplift – and placed it above girdled corsetry (sometimes even over the clothes themselves). It was a contemporary refiguration of the history of lingerie – and thus suggested that it is prime time for us to remember how the modern bra came to be, and the economics and politics behind the recent history of female silhouettes. Here, we trace the evolution of the bra over the past century: from flapper-style androdgyny to the buxom 50s, all the way through to where it stands today...

The Gamine Years

The first reported mention of a 'brassiere' was in American Vogue in 1907, and by 1912 Queen Magazine was already proclaiming that 'The Stylish Figure of To-Day requires a Brassiere.' Although they were already being worn by fashionable ladies, it wasn't until 1914 that Mary Phelps-Jacobs is credited with patenting the first bra – the charmingly named Caresse Crosby – which consisted of two silken handkerchiefs tied together, with ribbons for straps and a seam which joined in the centre.

Following centuries of tightly laced corsetry, the development of this new form of support offered a kind of physical liberation for women previously contorted into hourglasses – and the new trend for gamine figures, pioneered by the likes of Coco Chanel, meant that hoiking one's chest up to give buxom impact was no longer a requirement (between 1920 and 1928, sales of corsets fell by a third). Instead, bras like the bust-flattening 'Symington side lacer' came into fashion, creating the perfect androgynous shape for underneath a flapper dress.

The Debut of the Cup Size

It wasn't until 1929, that Maidenform Brassiere Company developed the cup system, whereby each specific bra size was determined by the ounces of the breast (previously, you just got your bra in small, medium or large). This new form of measurement offered more comfortable and accurate fitting, and coincided with the development of a new type of elastic thread by Dunlop chemists (called Lastex), which had the flexibility and strength to offer support instead of heavy boning and lacing.

Elasticated fabric panels and straps sat alongside separate cups, specified to your shape's requirement, and bolstered by underwire for lift: the bra, as we now recognise it, was born. Additionally, its new form meant that no longer did women need to rely on the assistance of their help to get dressed or undressed: bras could be worn by even those women who might not have a maid-in-waiting, and with the size and shape of their bodies taken into account, things got slightly more comfortable.

Wartime Austerity

Fabric shortages during WWII did more than just alter the height of hemlines: they were also responsible for the creation of the 'utility' bra – a made-to-order undergarment created out of minimal amounts of nude-coloured broche. Worn by women during factory and fieldwork, these pieces needed to offer sturdier and more practical support than previous incarnations – and were responsible for the new, more pointed silhouette of the torpedo bra, which was rumoured to add protection to women on the production lines. Bras were not a choice – in fact, as aerospace engineering company Lockfitt Corporation decreed, they were synonymous with patriotism, offering "good taste, anatomical support, and morale".

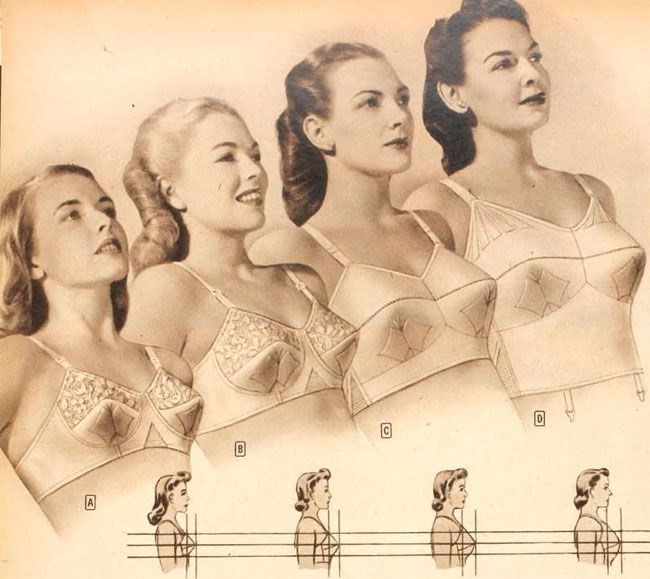

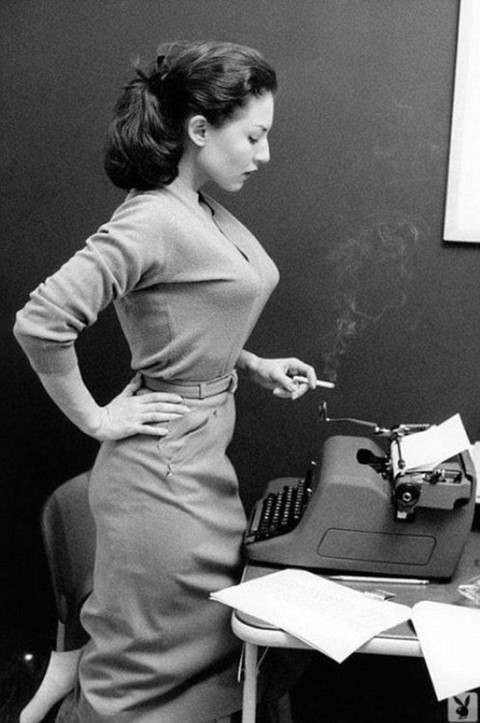

The Fabulous 50s

Following the stark austerity of the 40s, the 50s saw women embrace Hollywood glamour across the board – and glamorous breasts meant imitating the bullet-shapes modelled by starlets like Lauren Bacall, Jayne Mansfield and Lana Turner. Circular-stitched conical brassieres offered an emphatic uplift and, when worn underneath tailored woollen sweaters, were all the rage. Plus, with developments in fabric technology, bras could now be made out of nylon, and thus became lighter and more attractive than their utilitarian 40s counterparts.

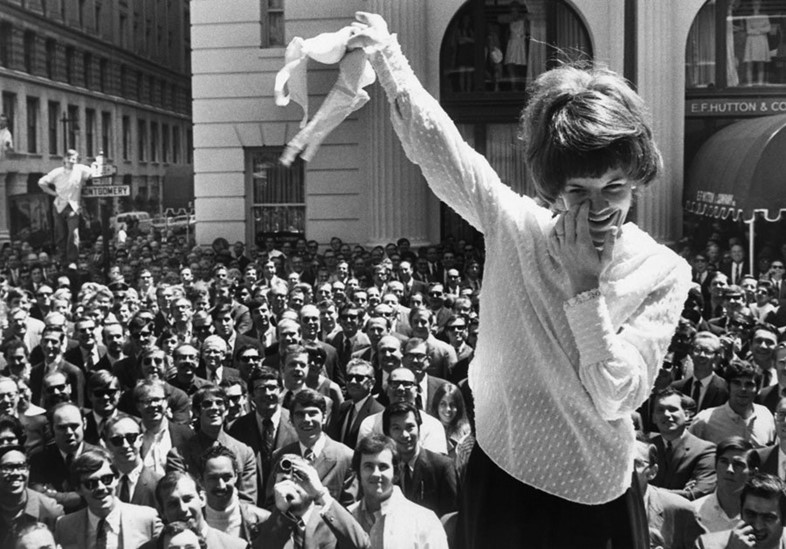

A Feminist Revolution

By the 60s, the bra had become a symbol of oppression: of the strictures placed upon women and the physical hegemony expected of them. Although the aphorism of bra burning feminists is commonplace, it is not entirely accurate; the stereotype is based on the Miss America Protest of 1969, where feminist group New York Radical Women tossed symbolic feminine accoutrements (including false eyelashes and mops) into a bin outside the Miss America competition. Their activism was considered analogous to the Vietnam protesters who burnt their draft cards, and thus the epithet was born. Nobody actually burned their bras.

However, the 60s did offer a movement away from the bra: see, Rudi Gernreich, who developed the no-bra bra (made of soft nylon that allowed for breasts to fall into a natural silhouette) and the controversial monokini (a swimsuit that left the chest bare). His designs were created in protest against the uniformly padded breasts of the previous decades – and were adopted and praised by women from Peggy Moffit to Twiggy. The era of free love promoted freedom in all spheres of life – and liberating one's breats from the (by now, quite rigid) brassieres on offer proved part of that. By 1970s, author Germaine Greer wrote in The Female Eunuch that "Bras are a ludicrous invention" and someone did actually publicly burn one – a 38C, on Lower Sproul Plaza in Berkeley, California.

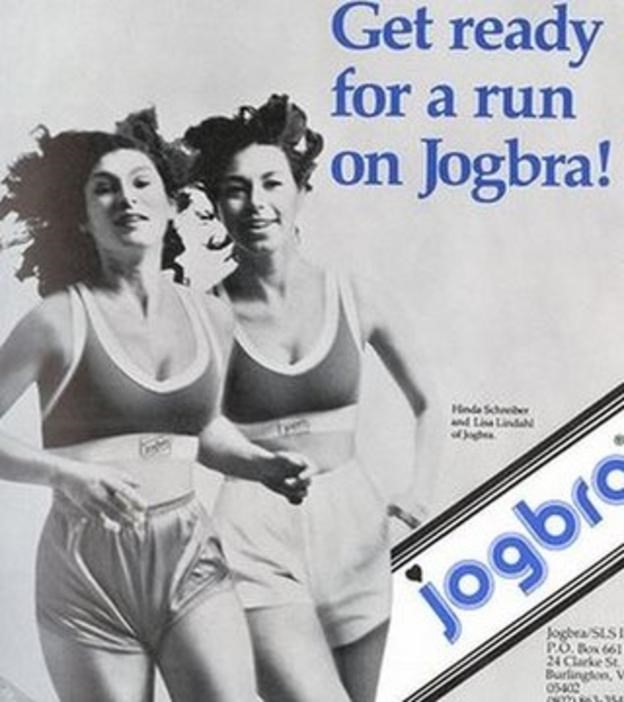

The Sporting Era

The 1970s saw the invention of the sports bra (then named the Jogbra)– a development clearly required considering that 20s athlete Violette Morris underwent an elective masectomy in order to progress in her career. Jogbra inventor Hinda Miller told BBC5Live that "We had witnessed bleeding nipples in the first 5km runs that were just starting to be popular in the 1970s," and with the increased proclivity for athletic physiques during the era (something that can be seen in the abundance of leotards and bodysuits in mainstream fashion), it became essential for women to have the support they needed to exercise however they chose. When off the sporting track, breasts took a more pendulous appearance; by this period, the bullett-shape looked dated and the natural silhouette that started trending in the 60s was in full swing.

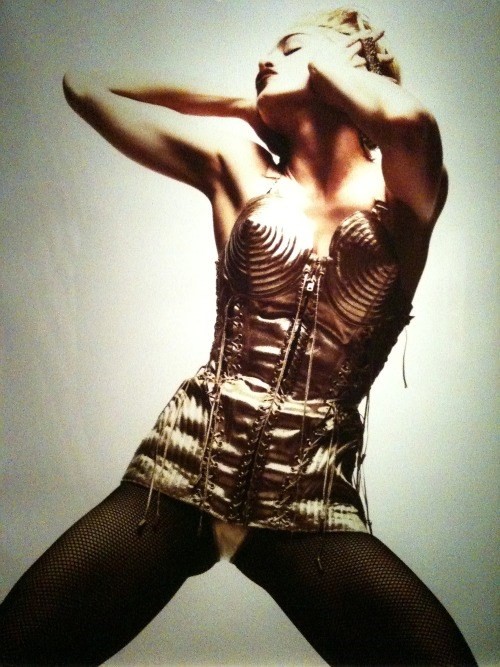

The Madonna Period

And then, there was Madonna: the woman who pioneered underwear as outerwear and enlisted Jean-Paul Gaultier to design what has since become perhaps the most iconic bra of all time, that which she wore on her 1990 Blond Ambition tour. Her costumes there subverted the binaries between masculine and feminine, turning the prettiest pink satin corsetry worn under pinstripe suiting into a potent figure of self-determined sexual liberation. It was a fabulously provocative moment and showed the power of the garment when used to challenge sterotype rather than affirm it; showing that the bra isn't intrinsically oppressive, and that context is what matters most.

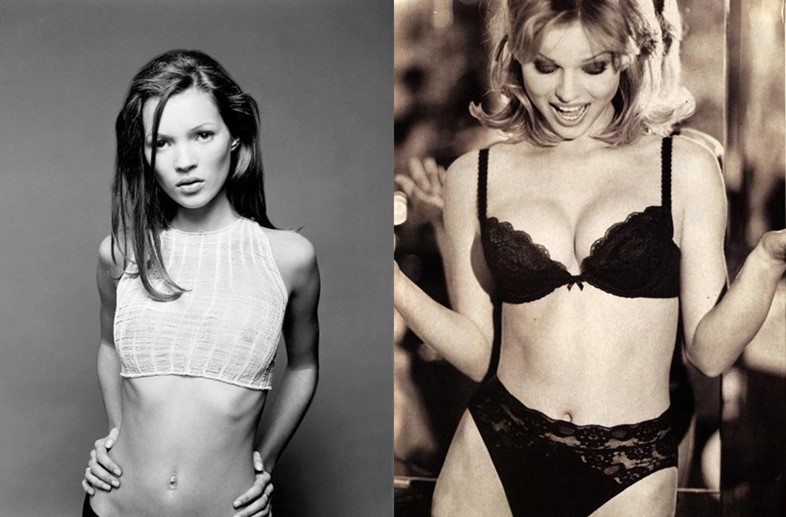

Androgyny Chic versus the Wonderbra

By the 90s, and the arrival of heroin chic, there was a determined division two particular approaches fashion took when it came to brassieres. There were the iconic, Corinne Day shots of a bra-less Kate Moss, effusing an effortless, androgyne sexuality... and then there was the Ellen Von Unwerth advert starring Eva Herzigova in a Wonderbra that purportedly caused car crashes. While these might seem like two very specific modes of female sexuality, what their polarity proves is that, by the nineties, there were options on offer to women. Want to wear something to go jogging in? You have it. Want a cleavage? Done. It turns out that it isn't the undergarment itself that dictates the confines of female sexuality, it is the culture that surrounds it – and by the turn of the millenium, the bra was just there to support our choices. It is this message that took bras into the 21st century: that whether you wanted to wear one over your clothes à la J.W. Anderson, not at all like Kate Moss or to enhance your cleave in the style of Eva Herzigova, you were no longer restricted by which garments were on offer... there might be societal pressures to contend with, but nobody is worrying about the strength of elastic anymore.