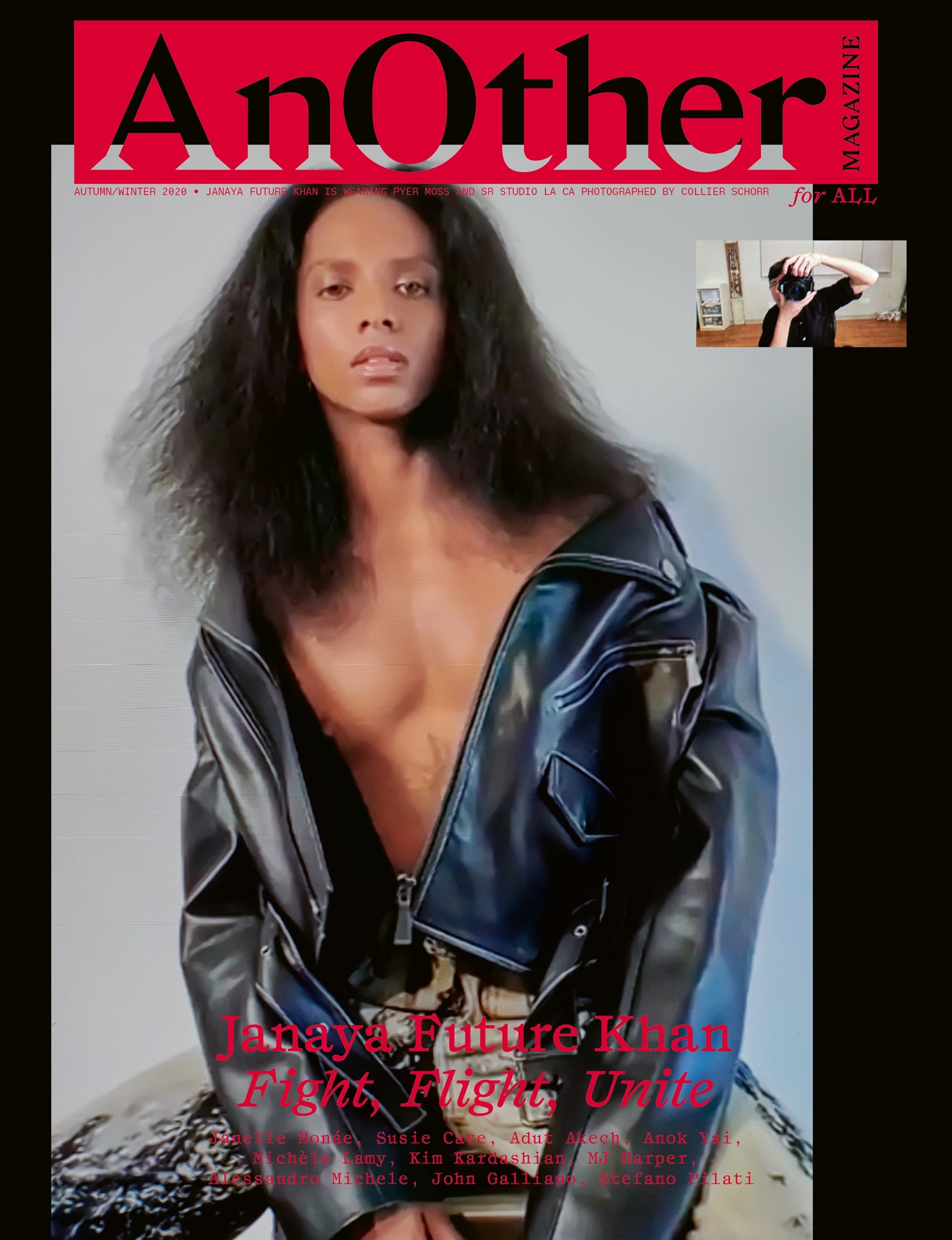

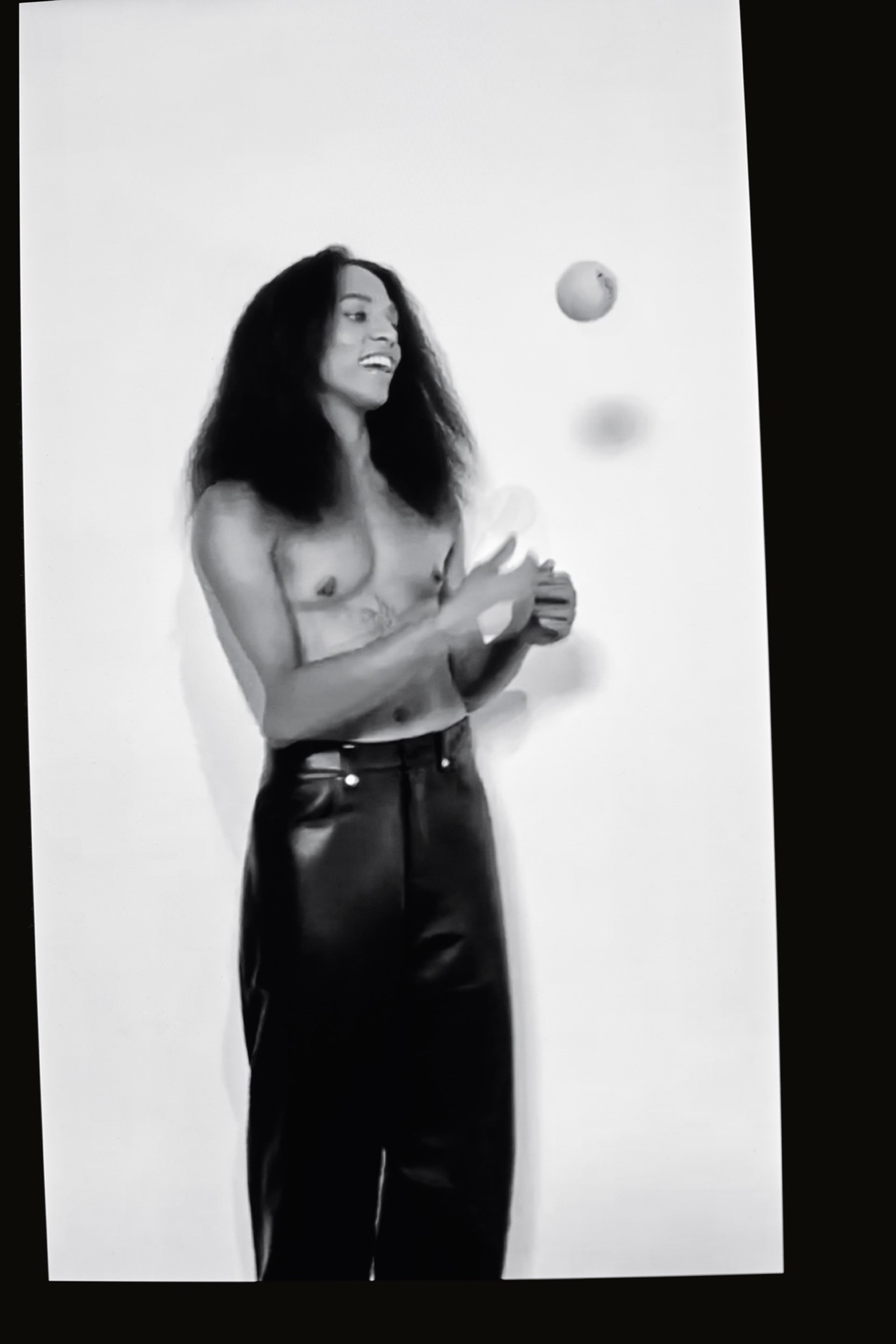

Janaya Future Khan has been tirelessly working for equality for the Black community since they were a teenager. It was in 2014, though, following the killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Jermaine Carby in Khan’s native Toronto, both by police officers, that they began fighting on the front lines of the Black Lives Matter movement as an international ambassador. They are a public speaker, teacher, author – and a competitive boxer. They also use social media as a tool for education, discussing queer identity, abuse of corporate power, Black feminism and police abolition. Their Sunday Sermons on Instagram have become an essential forum for understanding and reflection.

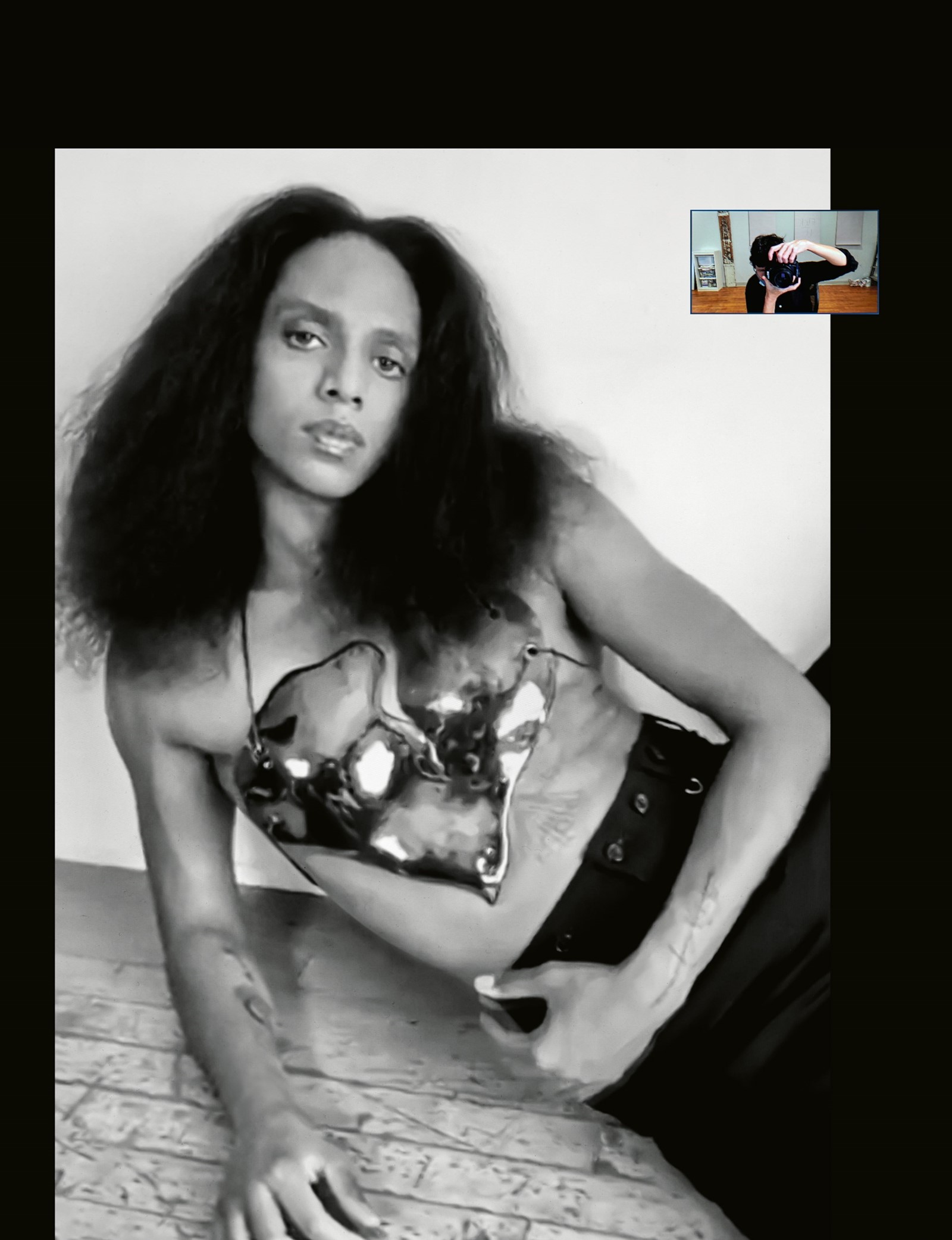

A constant source of inspiration to Khan is the singer, actor and producer Janelle Monáe, who herself is an important voice in the fight for racial equality through the umbrella of her Wondaland Arts Society that she positions across music, film, branding and activist causes. Her film roles, including in Hidden Figures, Moonlight and most recently The Glorias, in which she plays the civil rights activist Dorothy Pitman Hughes, chime with her vision to tell the forgotten stories of Black women. As an activist, she created Fem the Future, a grassroots initiative that seeks to create opportunity for all those who identify as women through the arts, mentorship and education. She is also a co-chair of When We All Vote, a non-profit organisation dedicated to decreasing the race and age gap in voting and increasing voter turnout during US elections.

Over the following pages, Khan and Monáe come together to discuss their formative years, the finding and claiming of their identities, the similarities in their shared experience of Blackness, the understanding of privilege and, critically, where we can go from here. It is a discourse that asks us to listen and learn about the stories we may have ignored or never considered. Despite the harrowing, centuries-long history of systemic racism, it was the murder of George Floyd that took the brutal treatment of the Black community out of the shadows and placed it at the forefront of the minds of people around the world. The unjust deaths of Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, equally, took us to a cultural tipping point. We spoke out, we marched, and marched, and marched, and vowed we would do better. Millions have called for change, but our actioning of that promise will be the measure for future generations.

ZOOM CONVERSATION BETWEEN JANAYA FUTURE KHAN AND JANELLE MONÁE, JULY 2020

Janelle Monáe: I am honoured and thankful to be called to interview you. How are you, love?

Janaya Khan: I am a pendulum.

JM: It’s such a heavy question. People text me, “How are you?” I don’t even respond because there’s so much to unpack. Are you in the States or Canada?

JK: I live in Los Angeles now. I chose the most opportune moment, in a history of opportune moments for people like us, to come to this country.

JM: Well, listen, I want to thank you for all the work you do for marginalised voices, for Black folks. When my fuel is running low I really look to you guys for inspiration. I want to touch on the moment you decided, “I’m going to dedicate my time to this, even if bills might not be paid, even if certain relationships have to take a backseat.” What was your family structure like, and what was that moment for you?

JK: Those are heavy questions, good questions. Family structure is a complicated one. When I look back, everything set me on this path. My father is Trinidadian and my mother is Jamaican and British, they both immigrated to Canada. My father, like so many of us – don’t we all dream we’re going to leave our mark and we’re destined for greatness? And those dreams are sometimes dampened by the reality and the social structure we live within. And I think that mothers learn out of necessity that they can work through their children for good or ill, and I think fathers sometimes become very destructive. So my family structure was very unstable, very unpredictable, and my mom was raising three children on her own with declining mental health. I went through the group-home system, the foster-care system, family shelters. That’s where I was when I started high school, and my first experience of activism was in those women’s shelters. Women who had been through impossible circumstances, they saw that this tiny family was struggling. It’s very difficult to start high school when you’re living in a women’s shelter, and they realised we were grappling with the shame of it. This was back when we called each other on landlines, and so when they answered the phone in the shelter, they would say they were our aunties. Someone said to me, “How many aunties you got?” I said, “A lot!” I was struggling, I was very angry, frustrated, and I didn’t feel like there was a place in the world for me. And despite the fact they were working through all this hardship and sadness, they were kind to me. When I look back, that was one of my most formative experiences of activism, which is just being for someone else who you needed most in your most vulnerable moments.

I wonder, Janelle, if you know that, for me, The ArchAndroid was the soundtrack. This was before Black Lives Matter came to be. Those of us who had been told to shrink our entire lives, Black women, Black girls, hyper-visible and invisible at the same time, ours weren’t stories that the world wants to hear. And feeling the injustice, and having nowhere to put all that energy, that rage, that frustration, that loneliness ... You feel like you’re losing your mind. I would listen to The ArchAndroid, I’d listen to Cindi Mayweather [Monáe’s android alter ego] telling the story – there’s love in it, revolution, and the Black experience was transcendent. It was queer, it was radical, you were giving it a language, and I felt less crazy. So your music was the soundtrack for the movement for me. I think you’re both of the people and also a bit prophetic, because the evolution of your music has also been in line with our movement. We spent the first few years really grappling with the idea that we had no leaders. People would say, “You have no leaders,” and we’d say we are a leaderful movement, because our movement was full of women. But because there was no single male leader we were cast aside. So, seeing the embrace of Black women’s leadership and Black queer trans leadership, despite all the pushback and the hate – this year is the seventh birthday of the movement.

JM: That’s truly something to celebrate. There are a lot of people who did not want this to be. Well, let me just say I had no idea you were listening to my work, or our work. Because early on in my career I dedicated my time to community and wanting to make sure it felt very inclusive. Following my inner compass was challenging, but I knew I wasn’t alone. I knew there were other androids out there searching and not wanting to fit into social norms or stereotypes, searching for comfort and community. So to know that any part of what I’ve done has impacted on what you’ve done is a big honour. How hard was it for you to fully understand your identity, what was your path in understanding who you are, and what helped guide you along the way?

“Protest is art, and we’re the curators” – Janaya Future Khan

JK: In my teens I wasn’t carrying some sort of repressed identity, I didn’t have any relationship to the politics of pleasure and desire at all. I was just living day-to-day, trying to get through. So when I discovered that I was queer in a really mundane way ... I don’t have this amazing coming-out story, it was through boxing. It was being, for the first time, in tune with my body. I walked into this all-women boxing gym – which is so gay already – and there were all these domestic violence survivors, dykes, trans people, people who had built this really remarkable community, and their existence was the invitation to me. Boxing has always run parallel to and informed my relationship to activism. When I came out as queer it wasn’t this big thing. Because I realised that queerness, and later on realising I was non-binary, it didn’t feel more significant to me than coming out as a freedom fighter or as a revolutionary. These things felt one and the same. I started to fight for Black Lives Matter because I am Black, but I fight for BLM now because I understand that Black liberation is integral for all liberation. And my job is to make this revolution irresistible. But I think what we’ve done, and I think what you’ve done, too, is we’ve cross-pollinated. You could have remained a musician, a world-celebrated musician, but you took more risk. A producer, an actor, a writer ... We cross-pollinate, that’s what we do. So this coming out that we do happens over and over, it’s an evolution of the spirit, because complacency is the death of the soul. So, when I think about this idea of coming out, it’s realising what we’re doing and committing to is so much bigger than our identities. We’re not trying to reframe colonialism to be more convenient, we’re trying to build a new belief system entirely. That’s the true coming-out.

JM: I know the shooting of Jermaine Carby was a big moment for Toronto. How did you become involved with Black Lives Matter?

JK: In Canada at the time we had a practice called carding, which is stop and frisk. And for a country that claims to be so much more evolved than its southern sibling, they’re brothers in bigotry. You were more likely as a Black person to be carded on the streets of Toronto at that time than you were as a Black person in New York City. When Mike Brown was killed, nine of us – and three of those were babies, in strollers – stood out front of the US consulate with signs, by ourselves. And then, months later, when Jermaine Carby happened, 5,000 people showed up. So there was a shift that we could feel. We started shutting down highways, freeways. Protest is art, and we’re the curators. Our job is to facilitate spectacle, to make it irresistible, get attention.

I think people don’t understand that protest is often the last resort. We’ve tried talking, we’ve tried showing data. Protest is the resort we use when all other realms of intervention fail. And maybe after our first highway shutdown we reached out to some of the organisers in the States and there were about nine of us crammed into one screen and we were talking about what it would mean to have a global movement. And then I came here to the States and began to operate as an international ambassador, so Palestine and Israel, Colombia when the workers went on strike in Buenaventura, Australia when the Aboriginal folks were rising up. And here I’ve been to almost every state where there was an uprising. We needed a media strategy, we needed organising routes on the blocks and to build up that infrastructure. It was difficult, during 2016, when Donald Trump was running for office and we could not agree on a strategy, because how can you have a strategy for that? We had to grow up in a very difficult way and fight with each other and debate and figure out what our responsibilities were in the world. To be wizards. Because that’s what it was, trying to do the impossible. At a time when the eyes of the world had turned away from us. So for everyone to suddenly love BLM is a bit disorientating, and of course it’s the time we’re in, it’s the pandemic, and the movement is always an open-arms thing, but it is disorientating. Because we had to fight to be seen, and now the world is seeing us, I think we feel an immense sense of responsibility to have tangible, meaningful wins.

JM: I was going to ask you about that. I know a little bit about what it’s like to work under pressure when things are moving in real time, and also what it means to be part of a community of folks who may have different ideas around politics. People don’t realise what goes into keeping a movement going, keeping the morale up. Talk to me about the times you’ve had differences with folks that you love in the movement and how you solved those. Because I’ve had moments within my own Wondaland family when we’ve had rigorous debates or we’ve gotten upset or stormed out, or just said, “Listen, I need a few days.” There are a lot of times when people say things that you may not be ready to receive. You have to sit back and be clear-headed because it’s not just you. You’re a puzzle piece in this puzzle and everything has to fit. So was there a time where you felt, “Hmm, I didn’t handle that well, this is what I learnt.” And, now, how do you deal with those moments?

JK: Absolutely. Ego. Feeding your ego doesn’t feed your people. I think for those of us who have been taught to shrink our entire lives, taught to be invisible, to run away from power, you either find yourself disappearing or you puff out your chest and try to make yourself as big and formidable as possible to show that they didn’t win. And there were moments when my chest was puffed out and I was like a little blowfish when I should have been listening more. I am a huge proponent of democratic discourse but I don’t always want to engage in it [Laughs]. And here’s what I learnt, and this was a moment of real humility for me – people need to get to wherever they’re going to get to on their own. We can never shirk the immense responsibility we have, those of us who are world shapers, discourse informers, world builders, which is what we are. When you invite somebody in, you can’t betray their trust. And I really thought about what kind of leader I wanted to be. Did I want to be the kind that told everyone they should be more like me, or did I want to help them on the path to be their most authentic selves. And that’s true leadership. When people can see themselves with you and not as you.

JM: That is a gem right there. You’ve been outspoken about the abolishment of the police. You say replace the police and put in justice teams, which I love. How can justice teams serve to protect communities going forward?

JK: We fought and we hoped and we worked, because hope is a discipline, hope is a muscle. And we tried to make this story meaningful, the idea that everything around us could be different. And it took the pandemic to bring home how unstable our sense of security truly is. In this moment where we had to witness this horrific murder of a man, George Floyd, at a time when we are being ravaged by a virus that is almost acting as a culling of the most vulnerable populations under a hateful administration. While we’re saying that essential workers, who are largely Black and brown people, their lives are meaningless. And even the old American gods, the tenants of success, like doctors and nurses, their lives are just as meaningless to the oligarchs as my own. This is an incredible moment of solidarity, a crack in the system, and we just rushed it because, finally, people are asking the right questions. So when the question came, “What’s to be done?” the answer was, “Well, what’s needed?” Housing, healthcare, food. That money is going to policing. How do we stop another George Floyd from happening? If there were an easier answer than defunding the police, we would have it. In fact, this answer isn’t as complicated as people think. The public education system has been defunded for years. It’s not about defunding the police, it’s about investing in our communities. Why shouldn’t a social worker respond to a mental-health crisis instead of a police officer? Why shouldn’t women call for help when there’s an issue of domestic violence without potentially co-signing their own execution? I guess what we have to ask ourselves is, what is it that police actually do well? It isn’t [dealing with] sexual assault, it’s not burglaries and robberies – their solving rate is almost non-existent, it comes down to insurance companies. What else, violent crimes? I’m not trying to put a vest on and run to stop the next mass shooting. But why do we need police for that? Why isn’t there a specialised team whose job it is to do that when it happens. We actually have all the answers and resources we need to build better systems. Even if you’re pro-cop, does it make sense to have the police as a one-stop shop for everything? From mental-health crises to domestic violence to sexual assault to noise complaints? No. So it’s time to build the communities that we deserve. It’s time for white people to betray the project of whiteness. This idea of police-free communities is not so far-fetched as people think. Because if you live in a wealthy neighbourhood, you are living with hardly any police presence at all. Is there anarchy in the streets? No. So that tells me the real concern is that the police aren’t going to be keeping people where they belong. That people who look the way we do are going to leave our projects and our ghettos and go into those communities and rob them. But here’s the truth – the best way to ensure you get to keep what you have safe is to make sure that everybody has enough. That’s it. It’s a very simple answer.

JM: You tweeted something recently – you said the movement of Black Lives demands, 1, reparations, 2, no bail, 3, the release of all prostitutes from jail, 4, no death penalty, 5, free education, 6, free healthcare, 7, defund the police, 8, cut the military budget, 9, redistribute the wealth, and 10, publicly financed campaigns. Talk about how you arrived there.

JK: It’s so funny, Fox News put that up as if to say, “Look at these rabble-rousers, look at how insane their demands are.” We looked at it and said, that’s exactly it! There is so much there, but there are a couple that don’t get spoken to as much. Publicly funded campaigns? Hell, yes. You should not stand a better chance at winning any kind of office in this country just because you have more wealth. Does that make sense? That wealth should inform who our champions of democracy are going to be? It is absurd. If we truly don’t want another Trump to happen, the answer isn’t to have a Kanye run for office. The answer is to eliminate the idea that wealth and access to it should inform who is going to hold the highest office in the world. Publicly funded campaigns would mean the citizens get to decide. And we absolutely need to eliminate bail. There are dark-skinned people and immigrants sitting in prison for absolutely no reason. They have not been judged guilty or innocent, they just are poor. Poverty has been criminalised.

“Hope is a discipline, hope is a muscle” – Janaya Future Khan

JM: The worst thing in America is to be poor. People say pull yourself up by the bootstraps. What bootstraps? We were never given any. It’s a whole system to make you pay for your poorness. Coming from a family of working-class folks – my mom being a janitor, my dad a trash-truck driver, my grandmother working and serving food in the county jail for 25 years, being a sharecropper in Aberdeen, Mississippi – community and service were always at the root. I’ve had several moments when the lights have been out, living with aunts and uncles until my mom and dad could get on their feet. When I was born, my mom had to get free milk – I’ve been on food stamps, the EBT [electronic benefit transfer] card. That was my life growing up. And the shame that people would make you feel if you looked poor. If, for Christmas, you were asking for a box from church when they were giving out food. Right now we’re doing Wondalunch programmes – giving out free lunch – and thanks to Gate Gourmet, we’ve given out up to 18,000 boxes of lunch in the past two months, trying to take that stigma away from asking for help. My situation now is not the same as a single Black mom with six kids who just got laid off. It’s so important we talk about our relationship with money and about what it means to redistribute. I’m still having conversations about capitalism and exploitation. Because I’ve seen people with money do amazing things, but at the same time I’ve seen how communities that I love and I grew up in are suffering as a result of not having that same opportunity.

JK: I think it’s beautiful, the meal programme that you do, it’s local organising. It changes the world, it changes national discourse. It’s community building, it’s relationship building. Because it’s not just about what you stand for, it’s who you stand with. That’s the future of activism, and I think this pandemic has made it more apparent to me, and I hope to many people, how much we actually need each other. Someone said to me once, “You feel otherworldly.” And I said, only because of you. The thing that is in us that is supernatural can only be accessed by other people. We can’t access it by ourselves. And this is what I want people to know: poverty is on purpose. It’s a manufactured reality, this idea of, “You get what you work for.” If people truly got what they worked for, based on hard work, single mothers would be the wealthiest people in the world. Nobody can earn billions of dollars, those realities can only exist because of the stolen wages of the working class. I don’t want to say that people who are wealthy don’t work hard, that would be absurd. But the idea that they work harder than people who are born into poverty, that to me is truly absurd.

JM: You say, and I love this, “The fight for Black liberation is integral for the liberation of all.” How do we spread the message that the action of the BLM movement is for the advancement of all?

JK: We do get competitive across the political left. It’s like, well there are Black people on TV right now, what about Asian-American representation? There’s a way that those of us who are oppressed and marginalised are fighting each other for the scraps, for any kind of recognition. And I think there’s an assumption, because Black people are such cultural producers, that we have all this systemic power as a result. And what I need people to understand is that we cannot allow our pain to be used against us. Because pain will make an island of you and you find yourself defending your oppression more than fighting it. Saying, “You can’t possibly know my experience,” as if your pain is unprecedented in the history of the world, to borrow from James Baldwin. In this moment of fighting for BLM, I see the Washington Redskins have finally renamed their team. That’s not a coincidence. Our job is to throw as much attention to each other as we can, and that’s how we all get free.

So what we need across the political left are some goddamn bottom lines. I haven’t seen them yet. Black people being killed by police was not a bottom line. Children getting ripped away from their families at the border was not a bottom line. The rollback of trans protections was not a bottom line. So we have got to decide what our bottom lines are across the political left. And it can’t be because the bigots and hatemongers are lobbing things like cancel culture at us and we’re throwing it around, debating with each other about the merits of it. That’s not ours to grapple with. Our job is to get really clear about what our bottom lines are. And one of the bottom lines has got to be that you believe my life is worth protecting and I believe your life is worth protecting. What I need people to know is that, when Black people win, everybody wins.

JM: I feel like we both have a deep connection to Afrofuturism, what it can mean for Black liberation. Talk to me about something that you dream of, that you know can exist.

JK: I want a world where education is free, healthcare is free and accessible, there is no debt. I want a world where Black women and girls are celebrated. I don’t want to live in a world where Atatiana Jefferson’s hashtag is just as prolific as George Floyd’s. I want us to end and abolish the system that leads to Black people dying in the first place. I want a redistribution of wealth. I want us to live in a system that is like penguins. A system that is community based. Penguins in the Antarctic organise themselves in a spiral. The penguins on the inside are warm and the penguins on the outside are cold, and gradually, over time, the penguins on the inside move out and the penguins on the outside move in and that’s how they survive. And to me there are folks who have been cold for far too long. And there are people who have been warm for far too long, they’re hot. We actually have everything we need already to create a better world. We need to have the radical imagination to do it. Somebody imagined slavery – shackles on Black people’s wrists – enough people believed it to make it true. Somebody imagined borders, enough people believed it to make it true. Somebody imagined police, and enough people believed it to make it true. Why shouldn’t we be the generation that imagines differently? Why shouldn’t we be the disruptors of truth in our lifetime and the diviners of change? The whole point of being on this planet is to live remarkable and extraordinary lives, and we do that when we fight in the service of other people. You want to leave your mark on the world? This is how you do it. No more being in that bed at night, wondering if this is all there is. Because if you’re asking yourself that, what you’re really asking is, is this all that I am? And if you have to ask that, the answer is no.

JM: I wish I could stand on every corner and give out the words you just said, because they ring so true to me. You’ve spoken a lot about privilege, you’ve said, “Privilege isn’t about what you’ve gone through, it’s about what you haven’t had to go through.” Can you elaborate on that?

JK: If I wanted a classroom to implode when I was in school, all I had to say was, “White privilege.” My God, it was a catastrophe! And as I started to do training and human rights work, no matter where I went, it was the same response, people lost it the moment I brought this up. And part of my job is to think about language, what it means to be a rhetorician, and I had to think about what people were hearing when I said it. What they were hearing is, “You’ve never been through anything in your life.” At a base human level, anyone who feels like their story is being erased is going to be defensive. And so I thought, let me see if a reframing of this helps, which is your story is your own. Can you live in wealth and also have a very difficult family situation? Yes. So this idea of what you haven’t had to go through, it should have inspired curiosity. And that’s one of the most important things about us as people – our curiosity. That’s how relationships stay alive, how movements stay alive.

JM: How we all stay alive.

“Why shouldn’t we be the generation that imagines differently?” – Janaya Future Khan

JK: Right. You really want to know how to win? It’s about community, and you can’t do that by only looking at your own experience. There are a lot of white folks now reading [Robin DiAngelo’s] White Fragility, which is fine. But white people cannot solve the problem of racial injustice by studying whiteness. There has to be a concerted effort to seek each other out. I am who I am because of everyone I have been blessed enough to meet. They have shaped what I know and what I thought was possible. And I think there are so many people in the world who have never had to meet or contend with people like you, or people like me. And if you don’t know me, can you truly say you know yourself? And if you don’t seek to know my experience, my life, my heart, my dreams, you have in effect accepted the conditions of bigotry, of hate, as your own. And when we complacently accept a system we’re born into, it may benefit our body but it decays our mind. We forfeit a part of who we are when we assimilate into a system that wasn’t ours to begin with, it’s just one we were born into.

JM: Wow. Listen, I hope that anyone reading this will share it to the mountaintops, to every ghetto and every suburb, every space shuttle – wherever there are ears listening, I pray that it falls on them. Let me end with something light, because I think balance is super-important when you’re in a position of leadership. In 2015 we put together a free concert series where, before every show, we went into the community and got with the mothers of those who had lost their children. We protested, we walked, then did a two-hour soundcheck, then a three-hour concert, and this was my life for a good few months with Wondaland. You’re organising in a different way from me, I don’t consider myself an organiser or an activist. You are an amazing example of someone who lives this, who breathes this – you do the work and I appreciate that wholeheartedly. But I do know that with leading, balance and mental health are so important. What do you do for pleasure?

JK: I spend a lot of time training, I box. I spend time with my dog. For the sake of being candid, I’m a huge fan of The Simpsons. The Simpsons was one of the most consistent things in my life when I was young, they were a family I had kinship with! I spend time with people – the people who love me know how to break me out of that pensiveness, they make me laugh, they tease me, and they don’t care at all about what I’m thinking sometimes, and that’s a blessing.

But I want to say this to you, Janelle. I don’t need you to identify as an organiser or an activist, but what I want you to know is that we have been walking alongside each other for a very long time. You were not some random name plucked out of a list of celebrities. To me, the greatest gift we have to offer anyone is our time. To be here with each other, that is an offering, the time you have given us, me, all the androids. Your evolution has been something remarkable to witness, and has been noted. That work and that presence, that daring, that risk – you were talking about these things when it was unpopular, too. You could have assimilated into something that would have been far more palatable, far more sellable, but you chose your integrity, and that’s not something that everyone can do. And that isn’t a judgment, there are so many circumstances that go into choices. But you gave us your time, you gave us your heart and you gave us your daring. And I want you to know that we’ve noticed. I noticed. And I knew what it was, I could see it because I was going through it, too. So if you ever have any doubt about yourself as an organiser or an activist, or any other thing, you should shed that. You’ve earned your stripes. You earned them a long time ago. Now you’re just honouring them.

JM: Wow. Thank you. I receive that. Look, you’re about to make me cry. You are otherworldly. I thought I was otherworldly! I really genuinely feel that we are on the same frequency. And it’s a beautiful thing to meet after all this time, but what is time? I feel your spirit, I feel your soul and I feel your deep love and connection for us. Thank you so much for representing not just myself but so many of us around the world who are choosing to remain radical, remain rebellious, choosing to use art as a way to heal, activism as a way to heal and connect. This will be a conversation that I will never forget. I would love to keep in contact and check in with you. Because people don’t realise that it takes a lot to answer the call. Just know I am in your corner, rooting you on.

JK: Thank you, Janelle. Same.

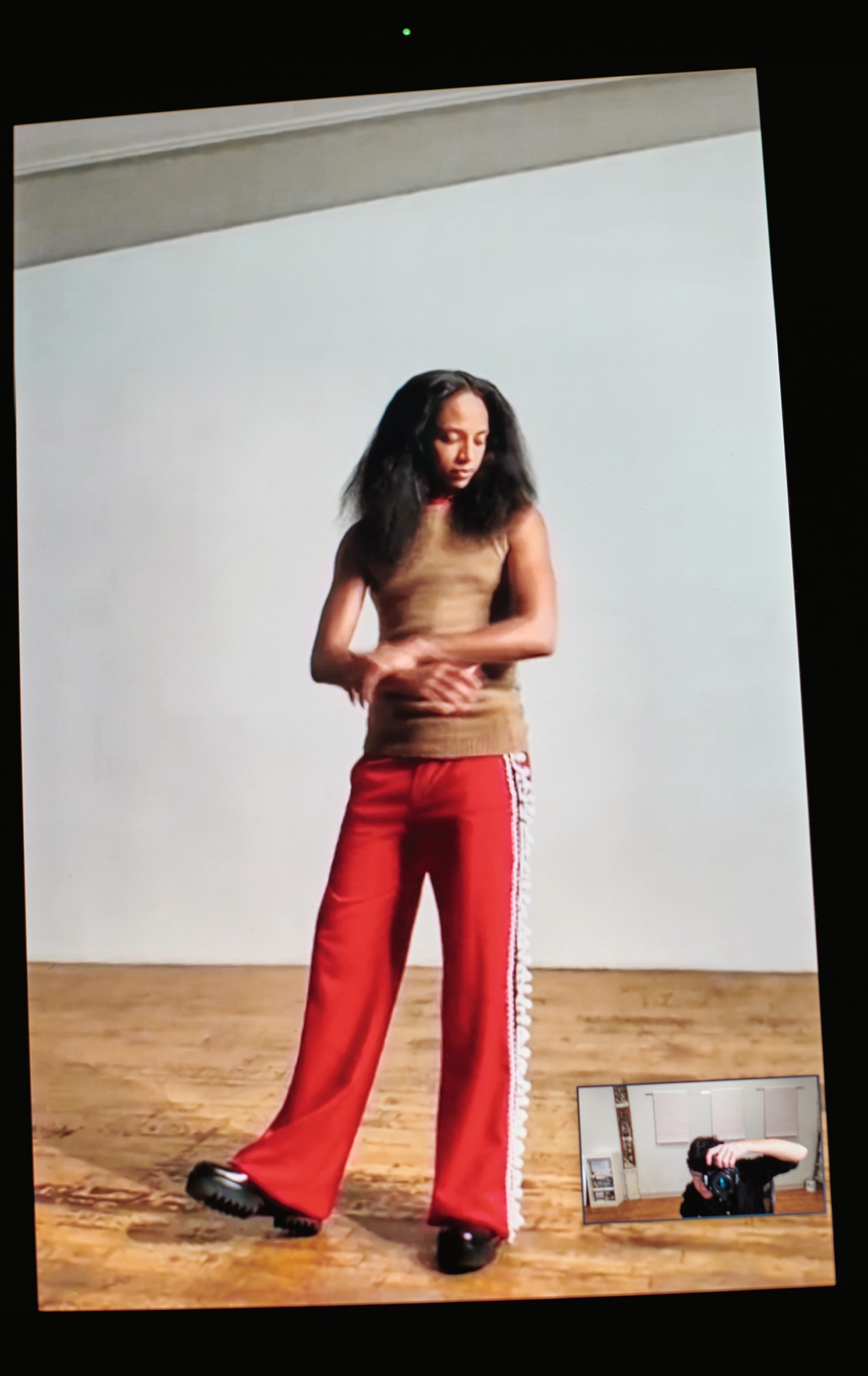

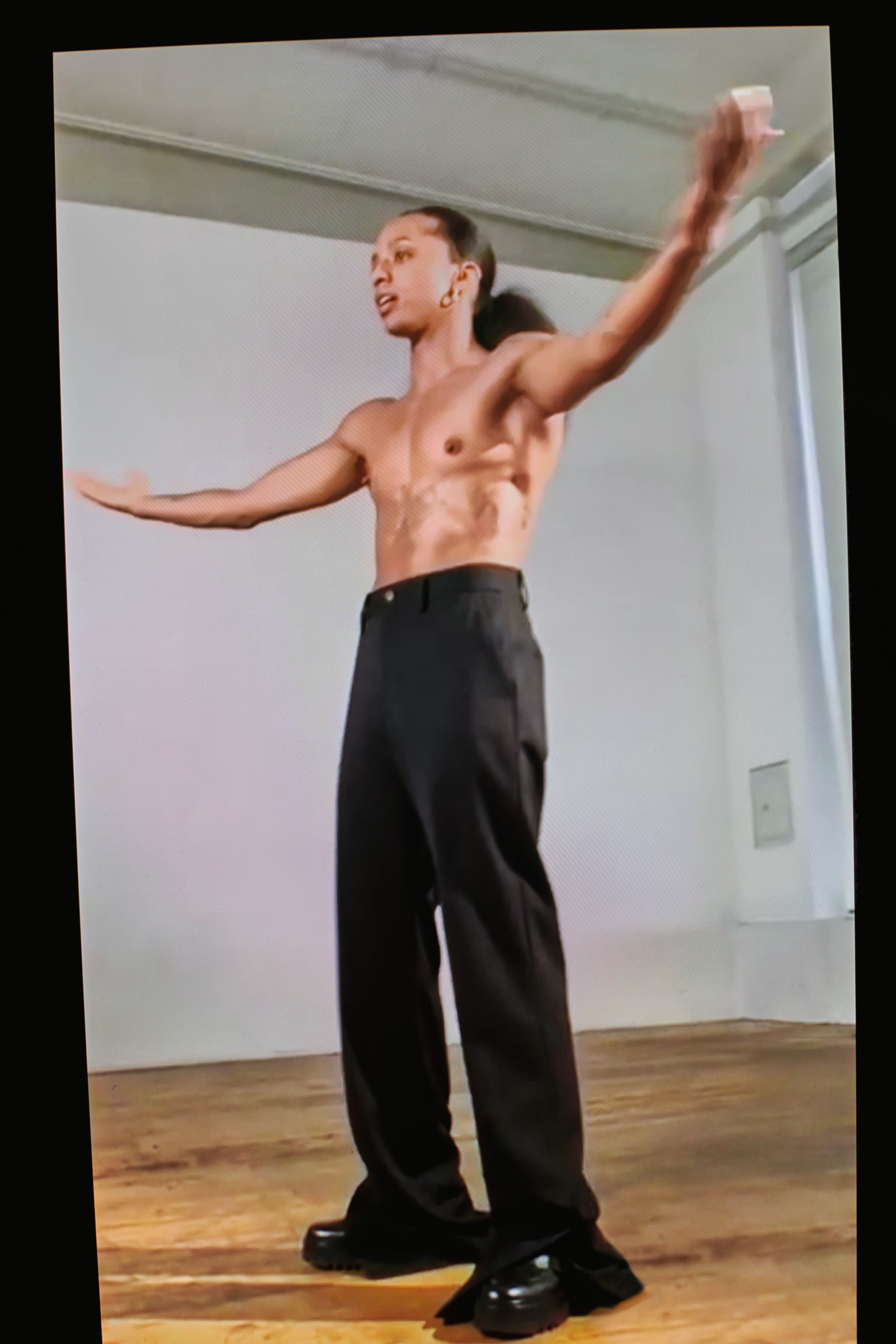

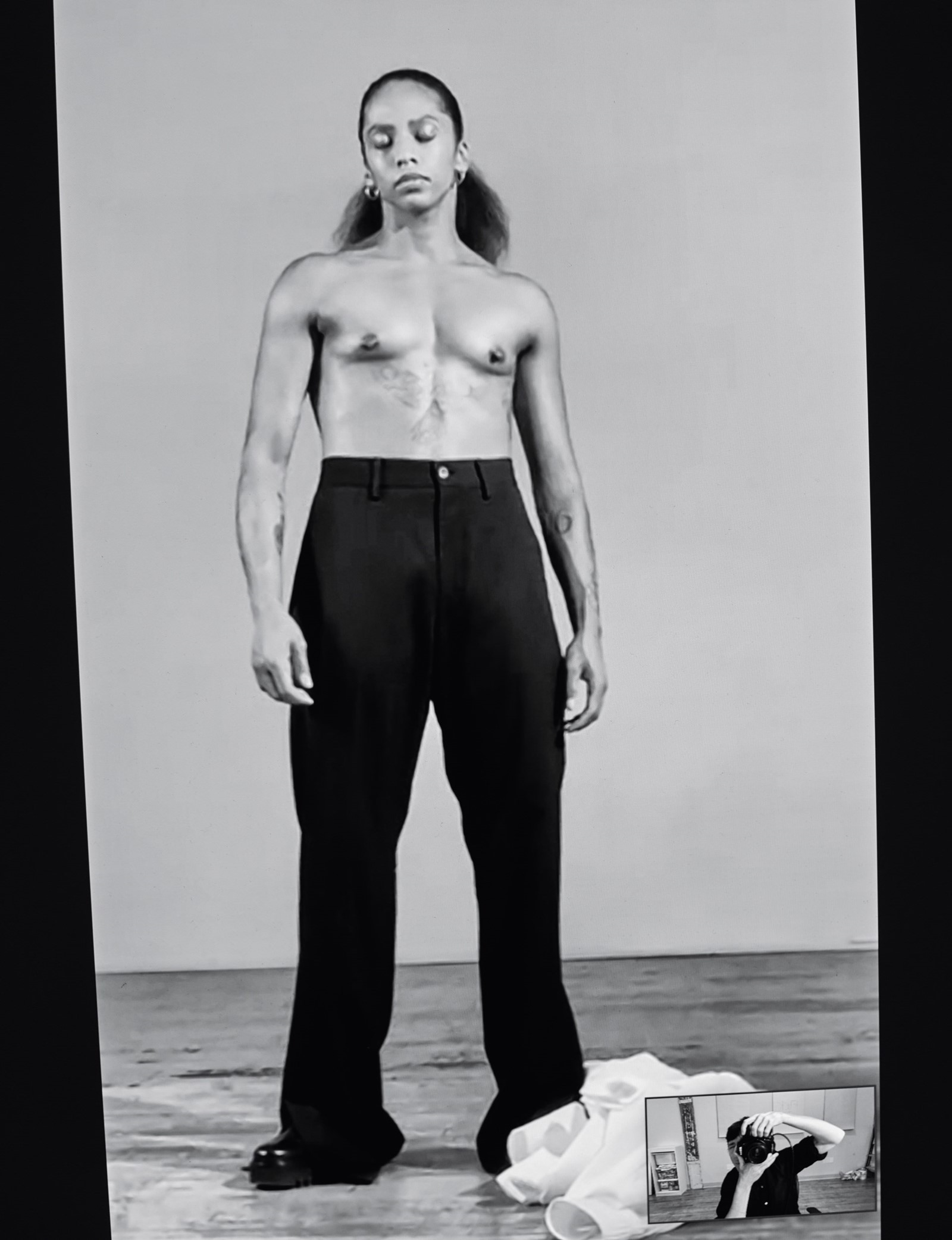

Hair: Rachel Lee Wright at Management Artists using PATTERN BEAUTY. Make-up: Molly Greenwald at A-Frame Agency. Digital tech: Jarrod Turner. Photographic assistant: Grayson Vaughan. Styling assistants: Rebecca Perlmutar and Megan King. Producer: Meghan Gallagher at Connect the Dots Inc. Production coordinator: Hannah Murphy at Connect the Dots Inc. Production assistant: Zack Higginbottom at Connect the Dots Inc. Post-production: Two Three Two. Special thanks to Adam Iezzi

This story appears in AnOther Magazine Autumn/Winter 2020, which is on sale internationally from October 1, 2020.