Oliver Meyrou spent three years documenting the making of Yves Saint Laurent’s last collections, only to have the film banned by Saint Laurent’s partner Pierre Bergé – here, the director opens up about his moving documentary

In 1998, at a screening of one of his films in Paris, young French director Olivier Meyrou was approached by Pierre Bergé, the erstwhile lover and lifelong business partner of Yves Saint Laurent, who asked if he’d like to make a documentary about Saint Laurent and his legendary couture house. “It was a very special time; the end was dawning,” Meyrou tells AnOther. “I think he wanted a last portrait of the house before it closed, and when he offered me the opportunity, I said yes, even though I knew nothing about the fashion industry. Saint Laurent was a mythical figure and I wanted to show the flesh and bone behind the genius.”

Meyrou spent the next three years documenting life at the atelier on Avenue Marceau, observing as the ailing designer produced his final couture collections and prepared for various milestones, including the spectacular retrospective runway show at the 1998 World Cup closing ceremony and the Lifetime Achievement Award that he was presented at the CFDA Fashion Awards in 1999. Filming wrapped in 2001, one year before Saint Laurent retired, but an ensuing legal battle with Bergé meant that the finished documentary, Yves Saint Laurent: The Last Collections, was banned from being released. It hit UK cinemas yesterday, some 18 years after the fact.

The passing of time has not dampened the effect of the fly-on-the-wall film, which provides poignant insight into the final years of “the last of the great Parisian couturiers”. “The house was like a miniature version of France in the early 20th century – you had the workers, the billionaires, the creatives, all under one roof,” Meyrou says. “The offices were in a Napoleon III-style mansion dating back to the late 18th century, and the way everyone moved and talked and interacted was like they were from a different era; like a Jean Renoir movie. Creativity was at the centre of every decision – everything was based on Yves Saint Laurent’s vision.”

The film paints a vivid picture of this bustling creative hub, honing in on the talented petites mains who so painstakingly brought Saint Laurent’s designs to life, agonising over rustling lining and imperfectly stitched velvet, as well as acknowledging other key cogs in the machine such as accessories director, Loulou de la Falaise and Saint Laurent’s beloved French Bulldog, Moujik. But it is the light it shines on Bergé and Saint Laurent, both as individuals and a collective force, that renders it so memorable.

Bergé occupies more screen time than the acutely camera-shy Saint Laurent. He marches around barking orders, reprimanding staff, and making sure that everything is up to Saint Laurent’s standards, of which he has an innate understanding. He is not afraid to direct his former lover either – as Saint Laurent practices his acceptance speech at the CFDA Fashion Awards, Bergé tells him not to slouch like “a doddering old man” – but, Meyrou notes, theirs was not a puppeteer/puppet dynamic.

“During shooting, I often imagined what happened the first night they met – when Saint Laurent was 26 and Bergé 32. They most probably made love and then in my imagination, which I think may be close to the truth, they woke up the next morning and Pierre told Yves, ‘You are the greatest designer on earth, and people will know it.’ That was their shared mission. It was like one eagle with two eggs, they were kind of the same person. In these later years, Bergé had become Saint Laurent’s spine, but it was always Saint Laurent who had the last word. Physically, he was the weakest man working in the house but he radiated a very powerful energy.”

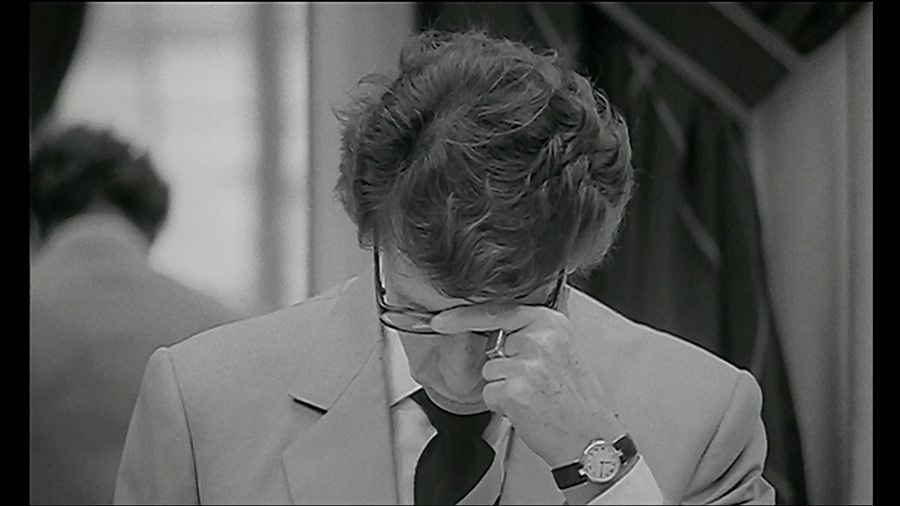

Although conveying Saint Laurent’s precise vision and the reverence he commanded, the film depicts the couturier in a melancholic light. During the shoot, he grows increasingly frail and tormented. In a 1999 interview with a journalist from Le Figaro, he expresses a desire to free himself from his “awful fears and anxieties”, but this, we see, is an impossibility.

“I only spoke to Saint Laurent three times during filming,” Meyrou says. “He was very impressive, but so in his own head – he was almost unreachable. The only thing we could do was observe him, like making a wildlife documentary.” Black-and-white and colour footage shows the designer lost in reverie or smoking cigarettes, as well as sketching and talking shop with his employees, all with an air of alienation and detachment. Experimental sound design from the late composer François-Eudes Chanfrault provides a haunting backdrop to the scenes – “we wanted to replicate the music he might hear in his own head,” Meyrou says.

As to why Bergé was unafraid to commit Saint Laurent’s painfully reclusive tendencies to film, Meyrou has a theory. “Saint Laurent was a tragic figure. From his early childhood in northern Algeria, he wanted to design dresses, to be famous, to have his name on the Champs-Élysées. He struggled a lot – being gay and effeminate at that time. I think his desire for fame was partially revenge. As Bergé says in the film, however, he paid a high price for achieving his dreams. But Bergé and Saint Laurent were not afraid of tragedy: they loved opera and embraced the operatic aspect of their lives. Bergé was also obsessed with preserving their legacy, and having his own role in the Saint Laurent story acknowledged. He had this very French grandeur about him.”

Interestingly, Bergé sued Meyrou (and thus prevented the film from being seen) before ever watching it himself. He finally opted to view it – thereafter permitting its release – in 2015, seven years after Saint Laurent’s death and two years before his own. “I don’t think he understood what documentary making was about,” Meyrou explains. “He was used to directing; to controlling all the imagery associated with Yves Saint Laurent and when I said he couldn’t be part of the editing or narration process, he didn’t like it. I also think he knew that we were documenting the end and it was too early for him to accept it.”

Yves Saint Laurent: The Last Collections will be in cinemas nationwide and on MUBI from October 30, 2019.