Fashion photography’s ability to mirror the times is one of the reasons it is such a fertile space for analysis. It would be reductive to say that this is merely due to the nature of fashion, constantly ‘updating’ with each new season. Rather, it is within the editorial images commissioned for magazines that worlds, characters and narratives are constructed around garments, providing us with clues to the social, political and economic factors that define a period.

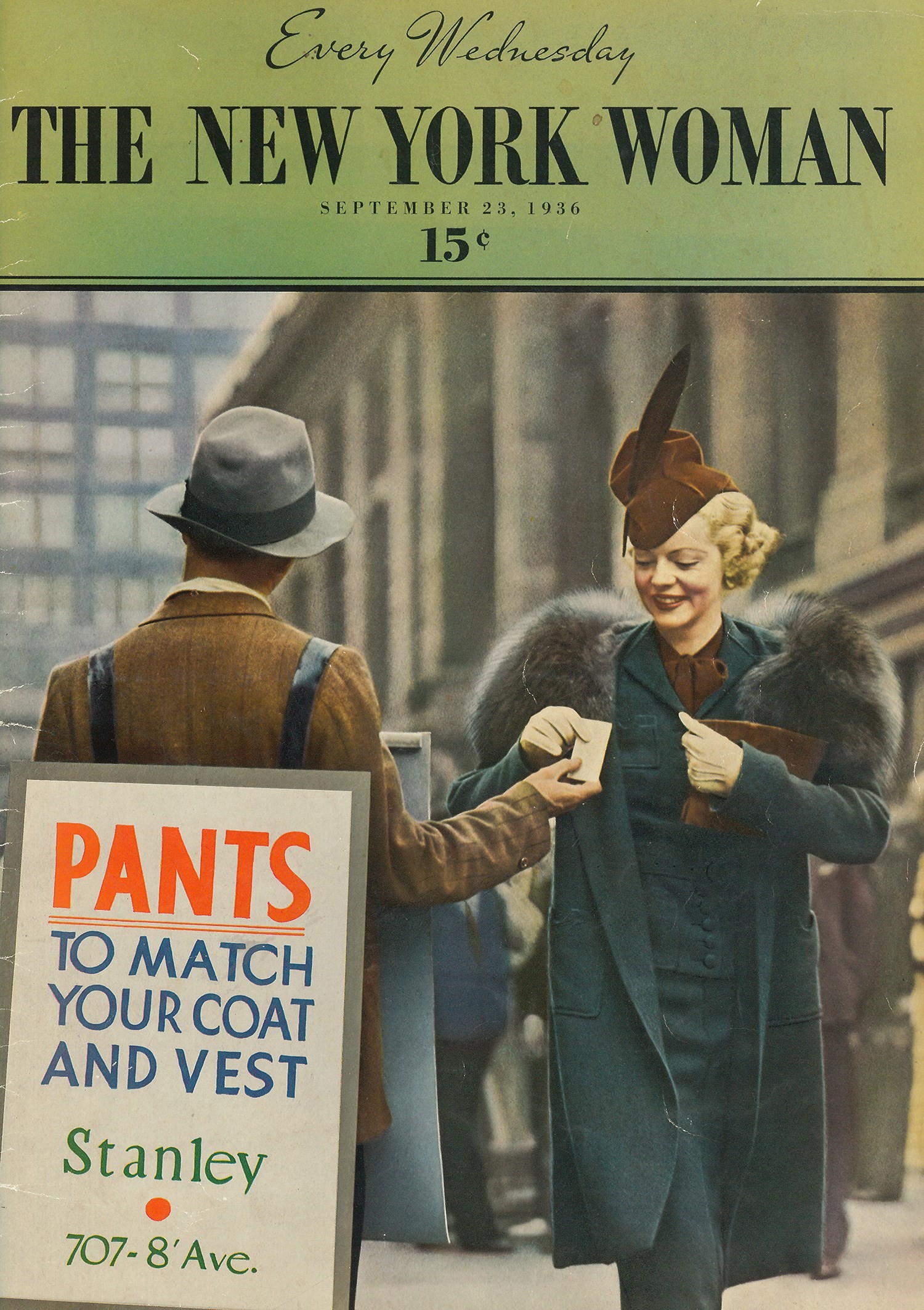

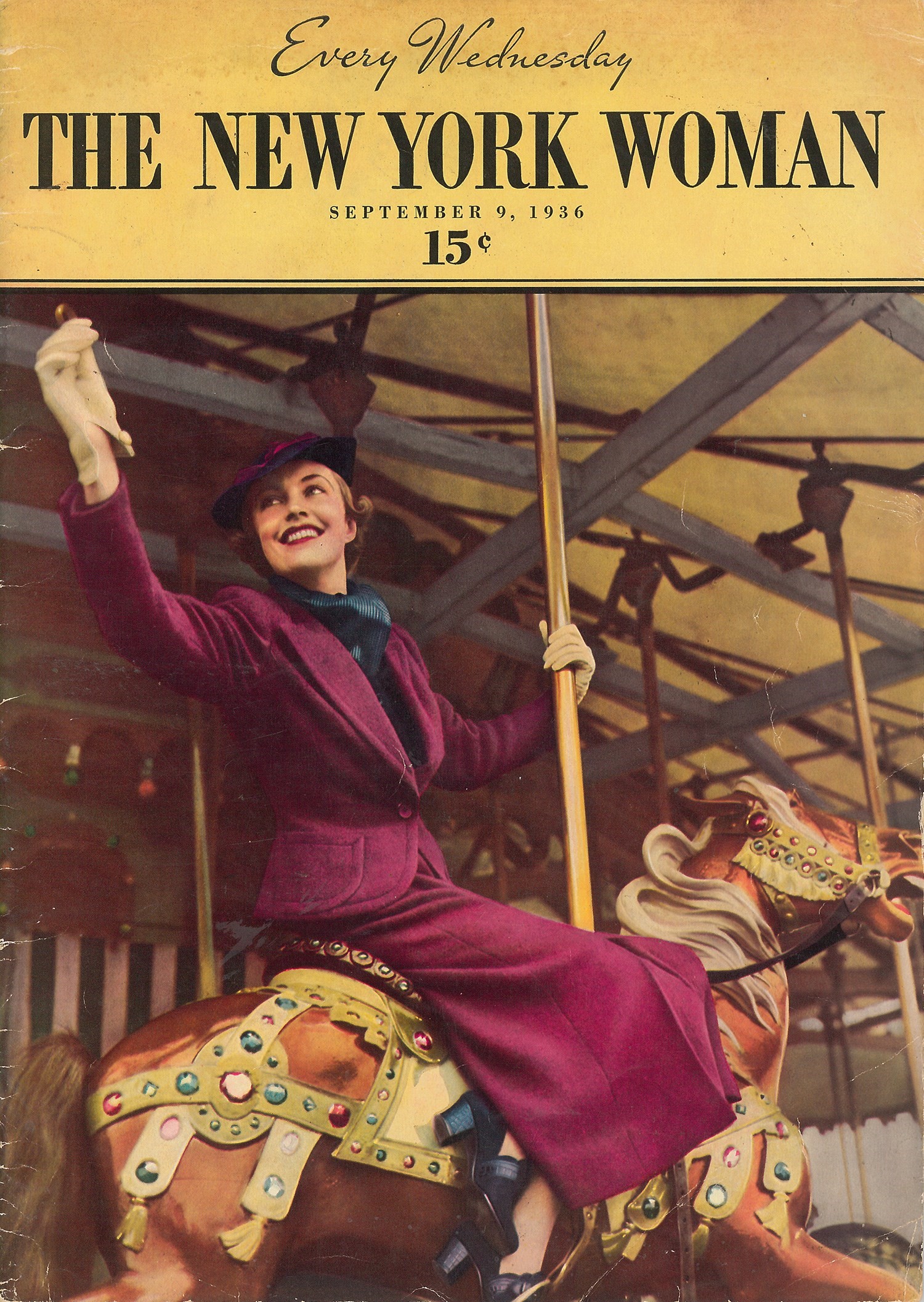

Night and Day: 1930s Fashion and Photographs, which opens at the Fashion and Textile Museum on October 12, 2018, does just this. Using fashion photographs, garments and magazines as historical breadcrumbs, it charts and explores the social changes that occurred throughout the 1930s. Interviewing the curators, Dennis Nothdruft and Teresa Collenette, it immediately became apparent to me that the decade held many parallels to the one we are living in now. It was a time of great social upheaval – the Great Depression of 1929 cast a lengthy shadow over the years that followed, much like the 2008 global economic crisis has with the 2010s, while the whole period hurtled towards the inevitability of World War II, which was announced on September 1, 1939. (This comparison is yet to play out, although the media alerts us to looming possibilities.) By 1933 almost half of the homes in Britain had a radio enabling rapid dispersal of information – a timely technological development akin to the way we carry smartphones in our pockets that constantly update.

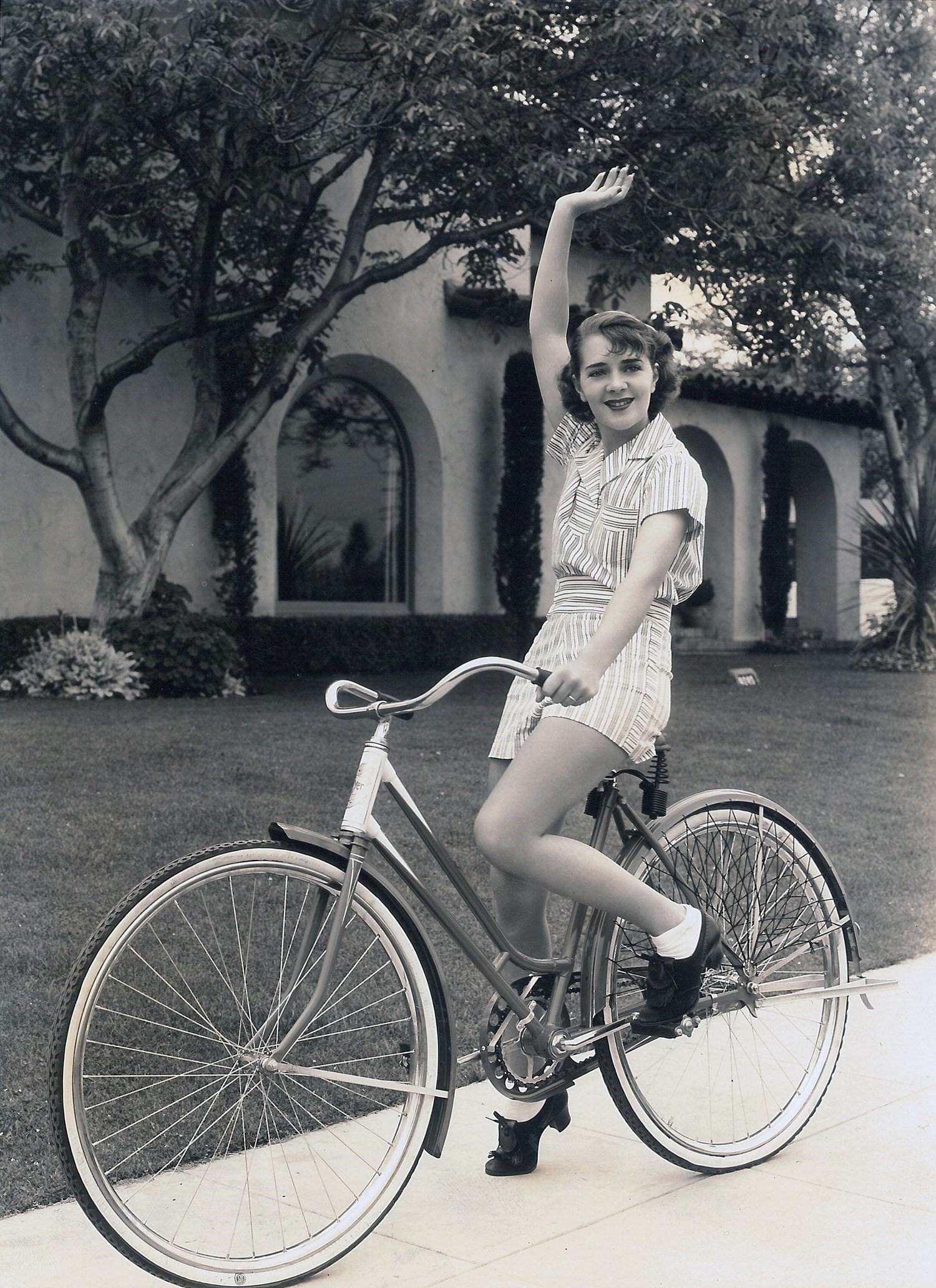

Using different formats, the exhibition builds a picture of the time, thematic sections unpicking the different facets of women’s life. Focusing on leisure activities such as nightclubs, the cinema and the rise of the seaside resort, it also looks at domesticity and the growth of suburbia, ending with a section on the Coronation of King George VI in 1937, in the wake of the abdication crisis of 1936. Fashion has such potency to evoke history – the fragments of DNA held within the fabrics, or the thumbed pages of a magazine becoming ephemeral cues which immediately place the visitor in the world these objects once belonged to. Featuring over 100 ensembles throughout, together with fashion and women’s magazines, the photographs on display are by the likes of Madame Yevonde, Paul Tanqueray, Dorothy Wilding and Cecil Beaton, depicting starlets and personalities such as Jean Harlow, Anna May Wong, designer Elsa Schiaparelli and writer Elinor Glyn. “After the 1920s Jazz Age: Fashion and Photographs exhibition we staged at the museum, it felt like the natural progression to explore the decade that followed,” says Dennis Nothdruft. Within the photography on display there is a sense of escapism and surrealism in the wake of testing times.

As Charlotte Cotton wrote in 2014: “We are just beginning to analyse the dynamic of fashion photography since 9/11 and in these turbulent final stages of late capitalism. What is generally understood is that the 2000s were a consciously and systematically conservatising and self-referencing phase of fashion image-making, perhaps logically obsessed with attempting to normalise consumerism and prompt desires through old ideas of glamour and celebrity.” These old ideas of glamour are constructed in the images made in the interwar period and although the clothing of the 30s was more sober and restrained, the photographs were fantastical, offering escape. Fashion historian Rebecca Arnold describes it as “a fascinating time when fashion photography is forming its own distinct vocabulary of styles, lighting and poses that will influence future decades. The relationship to fine art is strong – with classical, Modernist, Surrealist and even Baroque influences. Hollywood is also an influence in terms of ideas of glamour and beauty.” Take the work of Madame Yevonde, who was a pioneer of colour photography; she dressed her society ladies as illusory characters or ‘Goddesses’, as the title of her best known series suggests. Her work exudes pomp and frivolity. Or the bubble set Cecil Beaton created to place his ‘Soapsuds Group’ – Baba Beaton, Wanda Baillie-Hamilton and Lady Bridget Poulett – among, in the iconic image from 1930. There is a humour at play, a sense of not taking things too seriously, which can also be seen in the images created by fashion photographers working today.

When I interviewed set designer Sophie Durham for Posturing, the book which became the culmination of a three-part project I undertook with Holly Hay, she explained that in her work with the likes of Johnny Dufort “it’s a modern attitude to have a sense of humour in your approach to fashion”. She continues: “Working in fashion and living in this atrocious moment, I think a lot of the success of Balenciaga and Vetements is because Demna Gvasalia is designing clothes that feel more real. They don’t feel unattainable, but people can still aspire to them; it’s an aspirational fantasy.” Let’s get real though; a Vetements checked ‘Western’ flannel shirt, with tassels, retails at £639. Paradoxically, fashion’s interest in societal issues remains an interest, providing something to rift against, comment and draw upon. The clothing featured in Night and Day, unlike those pieces displayed in the fashion images exhibited, belonged to middle class women. From a private collection, they are their best clothes and ape the fashions of the day, based on styles by designers such as Vionnet. This allows the viewer to gain a more rounded view of the way in which women dressed. The majority of fashion exhibitions mount garments that were the high fashion of the day, exclusive and largely unobtainable.

The show also charts the birth of the women’s magazine, which breathes contemporaneous gossip into the display. Woman’s Own, which was first published in 1932, as curator Collenette explains, “was primarily a reaction to the emergence of a new form of domestic ideology that redefined the role of the housewife in the interwar years. Domestic ideals were championed in anecdotes and stories reflecting moral and social situations while ‘experts’ answered women’s anxious queries on a variety of subjects. The magazine’s chatty editorials encouraged women to trust the magazine and identify with it.” These columns transport you to the period in which they were created. One stood out: a woman writes to Modern Women: Health Club and Mother’s Circle, worrying her children are eating too much bread. Dr. Mary Denham chimes in: “Bread has the highest energy value of all foods. If the children have normal digestions as appears to be the case, as they are strong and healthy, you will probably get the best value for money – from the health point of view – by providing wholemeal bread – as this contains all the minerals and vitamins of the wheat grain.” What would the modern form of agony aunt, the Instagram wellness influencer have to say about that?

Night and Day: 1930s Fashion and Photographs runs until January 20, 2019, at the Fashion and Textile Museum, London.