In her Dior ready-to-wear collection last September, Maria Grazia Chiuri’s first look posed a question – literally. It was a slogan T-shirt which read: ‘why have there been no great women artists?’ – a question posed in an essay by feminist art historian Linda Nochlin about the systematic exclusion of women from art history.

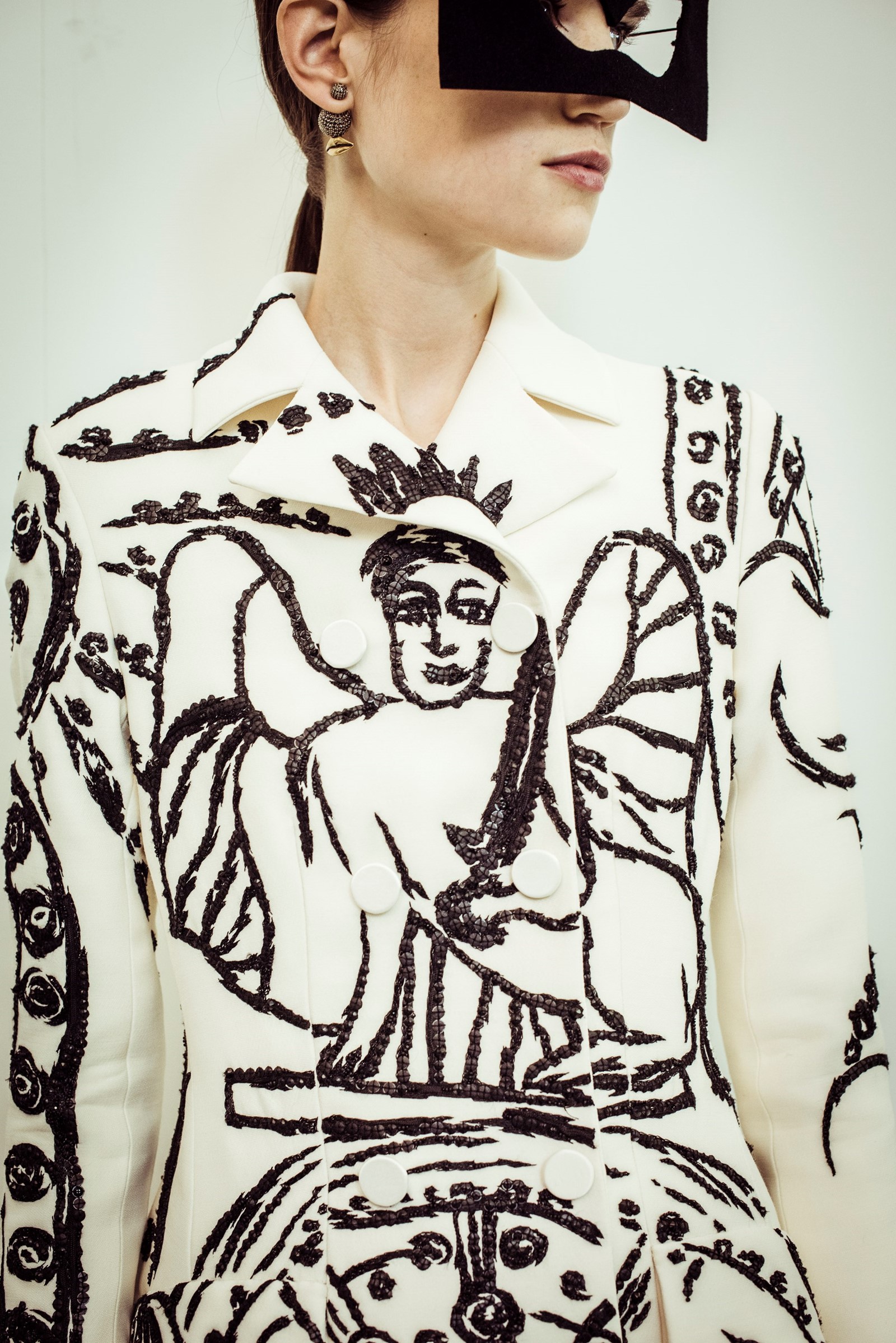

Christian Dior’s spring haute couture collection can be seen as something of a riposte. Based on Surrealism – a movement which, while often misogynistic, conversely gave a number of female protagonists boldface recognition. The Surrealists also had a deep interest in fashion – Dalí illustrated for Vogue, designed department store windows, and collaborated with the Italian couturier Elsa Schiaparelli, and the clothing and maquillage of women as depicted in fashion magazines featured heavily in the artwork of many of its proponents. Chiuri dedicated the collection to one – Leonor Fini, an Argentinian Surrealist artist raised in Italy, who left that country for Paris (shades of Chiuri herself) to make her name and fortune. She painted the rich and powerful – both in monetary terms but also artistic value. She also collaborated with fashion, designing the flacon for Schiaparelli’s perfume Shocking (a torso, based on the form of Mae West).

Fini isn’t the fin of the inspiration in this collection; though Maria Grazia Chiuri may have been inspired by a singular woman, she also included a number of outfits dedicated to other key female artists of the period, and additional pieces clearly inspired by their work. If you don’t dissect it, this collection seems a straight-up homage to the Surrealists’ realm of the kooky and arcane, checkerboard floor, stucco-coated drapes and plaster cast dancing extremities all counted for, but, in actuality, it’s subtler and more intelligent, charting the position of women within the art form and taking inspiration from their work in particular.

Here, we spotlight a selection of the major players in the movement, and on Maria Grazia Chiuri’s Dior haute couture mood-board.

Lee Miller

Later famed for her fearless work as a war photographer, in 1929 Lee Miller was a 22-year-old American sometime Vogue model enamoured with Surrealism who became apprenticed to the celebrated Parisian-based art photographer Man Ray (actually a Brooklyn import born Emmanuel Radnitzky). Miller and Man Ray became lovers, but also collaborators – Miller not only posed for some of the Surrealist’s most highly regarded works, but helped invent a technique indelibly associated with his aesthetic – solarisation. It was Miller, rather than Man Ray, who turned on a light in the darkroom while a set of negatives were still developing, to create the visually distinctive photographic technique. Miller was a figurehead for the Surrealist movement – her circle included Pablo Picasso and Jean Cocteau, who had Miller play a classic statue for his avant-garde 1930 film Le Sang d’un Poète (she was coated in butter for the role – her only cinematic appearance). Dior not only named a dress after her – a nude, beaded look also evoked Miller in Man Ray’s famous solarised portrait studies.

Méret Oppenheim

Méret Elisabeth Oppenheim was the Swiss-born artist whose 1936 sculpture Object (Breakfast in Fur) became, arguably, the physical emblem of Surrealism – a cup, saucer and teaspoon covered in Chinese gazelle fur. Alongside the impracticality, incongruity and unpleasantness of this notion, there are clear references to female sexuality – crude, but simultaneously complex. Inspired by her own dreams and the discovery of the writing of Carl Jung (a friend of her father, a German-Jewish doctor), Oppenheim’s work often consisted of everyday or domestic objects arranged to surreal effect, alluding to both female physicality and sexuality and feminine exploitation by men. Another piece, consisting of a pair of white high heels, trussed-up like a turkey and titled My Nurse, so enraged a female observer she destroyed it when originally displayed in 1936. Oppenheim’s furred teacup was nodded to in dresses with unusual fuzzed textures – like the eschelle of fluffy white butterflies decorating a stark black evening gown, or a fluffy feathered bodice gripping the waist.

Dora Maar

A pseudonym of a woman born Henriette Theodora Markovitch – invented identities were very much part of the Surrealist mood of 1930s Paris – Dora Maar is now perhaps best known as a lover of Pablo Picasso, immortalised in the Weeping Women series. But Maar’s photographic work was emblematic of Surrealism: she created photomontage pieces in silver gelatin print where disembodied hands emerged from seashells and faces are veiled in cobwebs or double-exposed to create an eerie blur. Both the cryptic dream world her photographs depicted, and the woman herself, helped define the Surrealist movement – alongside her own work, she was photographed by Man Ray and drawn by Cocteau. She not only inspired Picasso’s paintings, but turned photojournalist to document the 36-day process of Picasso painting Guernica, an important art-historical document. Her role as Cubist muse was evoked by Maria Grazia Chiuri in a series of intentionally abstract patchwork dresses, while the floating metal and tulle masks, created by Stephen Jones, could have been cut from one of her striking photographic works.

Dorothea Tanning

Less immediately recognised than these other muses, Dorothea Tanning was a late Surrealist whose little-known story is fascinating, and whose work remains striking and enigmatic. Originally a commercial artist, born in Illinois and then based in New York, she discovered Surrealism via the Museum of Modern Art’s seminal 1936 show Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism (where, incidentally, Oppenheim’s Object was displayed – it was the first artwork purchased by MoMA). In 1942, she met the artist Max Ernst who would later become her husband: he was, according to her, seduced and obsessed by her self-portrait Birthday painted around the same time and four years later they married in a double wedding with Man Ray and Juliet Browner. Tanning’s self-portrait – where she wears raiments of Renaissance costume and a skirt that on first glance could be feathers, but subsequently seems to be roots – could have been the inspiration behind the similar plume-embroidered evening dresses in Dior’s striking, Surreal spring couture show.