"To my misfortune, and maybe my delight, I place things according to my love affairs," Picasso once remarked – and this summer, a new book puts the women who inspired the artist well and truly in the limelight

Everybody knows the name Pablo Picasso, that of the groundbreaking artist whose bold innovations, prolific skill and modern fascination with the female form cemented his position as one of the most exceptional artists of the 20th century. Women play an essential but complex role in the father of cubism's sprawling oeuvre, expressing emotion, psychological insight and the drama of human existence respectively, but, renowned as Picasso was for being a serial philanderer, the stories behind the faces in his frames are considerably less well known.

This summer, a new exhibition and accompanying book, entitled Picasso: The Artist and His Muses, seeks to explore and rectify this imbalance, focusing on six women who played an unforgettable role in Picasso’s life and work. Each lover can be seen to correlate with a different moment in his consistently evolving artistic practice, from 1906 through to the early 1970s, and their portraits create a fascinating counterpoint to their individual stories – sometimes joyful, occasionally defiant, often tragic in their sudden endings. Regardless of their conclusion, the exhibition and accompanying tome, written through with texts by curators and critics, highlight the stories of the women behind the portraits, paying attention to their own fascinating histories and tracing the myriad ways in which they shaped the prolific artist's career. Here, we present six of them.

Fernande Olivier

The life of Fernande Olivier, née Amélie Lang, was complicated from its very beginnings: she was born out of wedlock, the product of an affair between her mother and a married man, and raised by an aunt who tried to force her into an arranged marriage. Determined to control her own fate, Lang ran away and married an abusive man of her own choosing. It wasn't until she left him at the age of 19, changing her name and fleeing to Paris to become an artist's model, that she met Picasso.

The pair began their bohemian relationship in 1904, before Picasso had established the notoriety that would later surround him, and from the start it was fuelled by jealousy. Olivier was forbidden from modelling for other artists, but she was to become the subject of some of Picasso’s early notable Cubist works: in creating Head of a Woman (Fernande) (1909), Picasso made two plaster casts of Olivier’s head, from which at least sixteen bronze examples were cast. The flat and planed surface of the sculpture linked the piece to his paintings of the same period, and played a seminal role in his development of cubism, catalysed as it was by the realisation that the painted plane could be translated into solid three-dimensional forms. He later revealed that one of the women in his 1907 masterpiece Les Démoiselles d'Avignon was modelled on Olivier.

Their tempestuous relationship dissolved in 1912 due to mutual infidelity, leaving Olivier destitute and unable to afford the lifestyle she had become accustomed to. When Picasso was at the peak of his success, Olivier began to write a memoir about their time together, publishing it in serialised form in the Belgian newspaper Le Soir. Picasso’s lawyers halted it by the sixth edition, every inch the 19th-century scandal, and a small pension was provided in recompense. It wasn't until 1988, when both Olivier and Picasso were dead, that the memoir was published in full.

Olga Khokhlova

Olga Khokhlova was an aristocratic Russian ballet dancer and a member of Sergei Diaghilev’s dance company, the Ballet Russes. She met the 36-year-old Picasso, already infamous for his conquests, when he was invited by Diaghilev to embark on an artistic collaboration. They fell in love and married in July, 1918, around which time, both to signal his commitment and to appease his Spanish mother, Picasso painted Khokhlova wearing the traditional Spanish ‘mantilla’ headscarf.

Over the course of their relationship, Picasso's artistic development progressed to a new level of experimentation, merging cubist shapes with more classic and realistic approaches, and experimenting with photography. Khokhlova’s experience in posing for promotional ballet posters made her an ideal sitter. Their child, Paulo, was born in 1921, and Picasso began to make work that explored motherhood, domesticity and femininity – namely, photographs and etchings depicting Khokhlova as a maternal muse.

Due to Khokhlova’s status, the couple attended balls and took holidays with other wealthy socialites. In 1927, however, Picasso began an affair with Marie-Thérèse Walter, a relationship which wasn't revealed to Khokhlova until Walter fell pregnant in 1935. She separated from Picasso and moved to the South of France. Throughout the rest of her life, Khokhlova preserved thousands of photographs and negatives of her 18-year-long marriage with the artist. Dated and annotated, they tell the poignant story of a unique family, and make up one of the most important records of Picasso’s life.

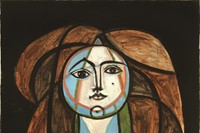

Marie-Thérèse Walter

Marie-Thérèse Walter was 17 and Picasso 45 when he reportedly stopped her as she was leaving the Parisian department store, Galeries Lafayette, with the infamous line: “You have an interesting face. I would like to create a portrait of you. I feel we are going to do great things together. I am Picasso." It is said that Walter’s proportions and bodily contours corresponded exactly to an ideal form that Picasso had imagined, and had been depicting, for two years previously. It follows, there, that soon after their affair began Picasso began making encrypted portraits, inscribing their relationship through the letter P interlaced with an M and a T – a romantic and engimatic code – and by 1930, the year Walter turned 21, her highly recognisable physical characteristics – classical profile, blonde hair, curves – began to appear without camouflage in all of Picasso’s work. She was omnipresent in painting, drawing, sculpture and engraving; Picasso often painted her seated, stretched out, or sleeping, the chromatic combinations expressing political, erotic and lyrical sentiments. Paintings of Walter were also infused with celestial connotations, often embedded with lunar symbols to visualise her as a goddess of love and fertility; a symbol of heavenly peace.

Their daughter Maya was born in September 1935, at which time Picasso met new flame Dora Maar, marking the end of his and Walter's clandestine relationship. The artist stayed in close touch with Walter throughout his involvement with Maar, but as had been the case with Khokhlova, Walter remained the private lover, and Maar the public. From 1944 onwards, her sculptural form didn’t appear in his work again, and in 1977, four years after Picasso’s death, Walter tragically committed suicide, hanging herself in the garage of her house in the South of France.

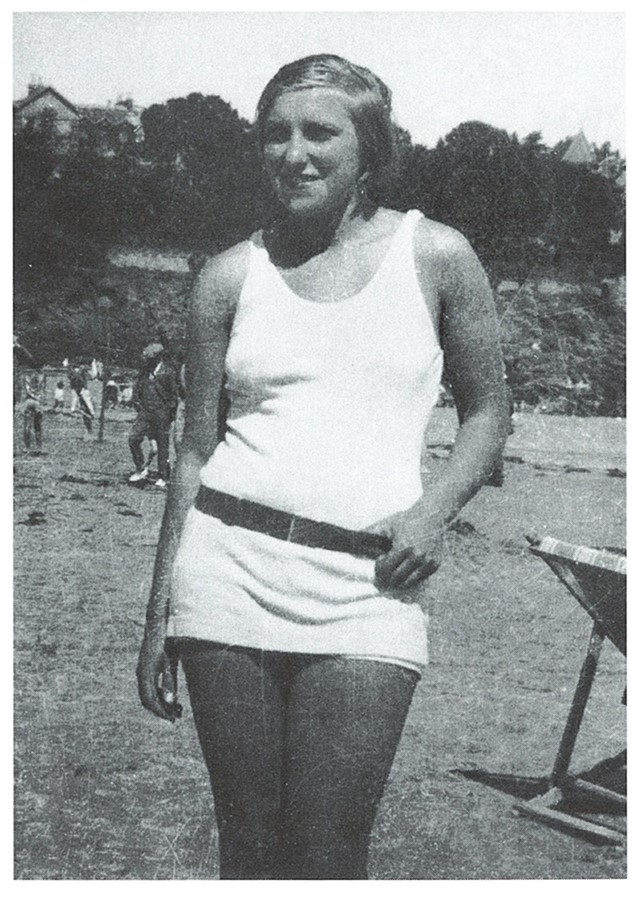

Dora Maar

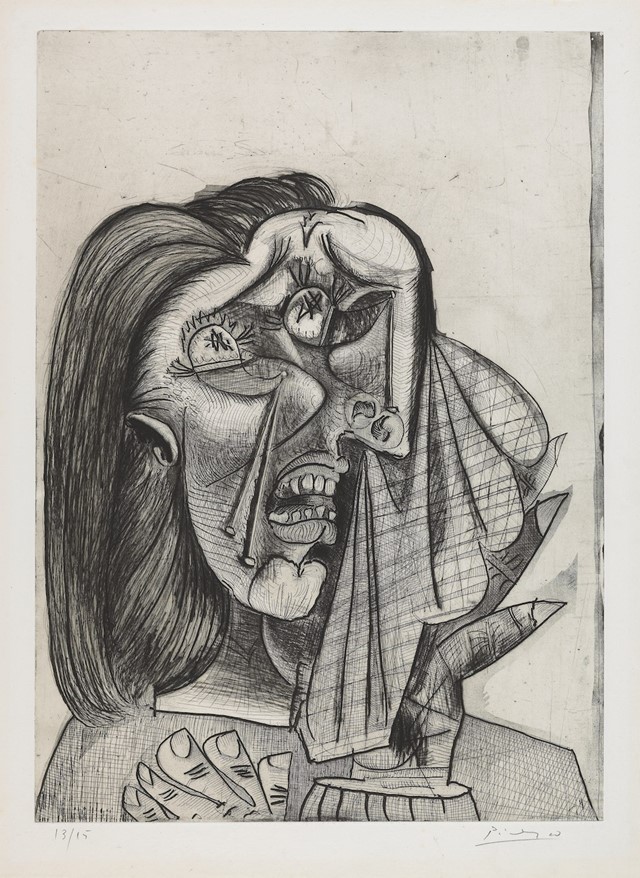

Dora Maar’s presence in Picasso’s life left an indelible mark on the work he produced during the prolific years of World War II. She was a respected surrealist photographer, sharing a studio with Brassaï, and was actively engaged with far-left, anti-fascist European politics. According to legend, Picasso and Maar were formally introduced at the Parisian café Le Deux Magots in the spring of 1936, when Maar was playing a risky game of stabbing a knife into the table between her gloved fingers. Maar cut her finger and Picasso kept the bloodied glove as a souvenir.

If Picasso found Walter gentle and passive, then Maar was intellectually and emotionally challenging. He represented her through torturous imagery, deconstructed angular forms and acidic colours. Together they studied printing with Man Ray, and experimented with new techniques combining painting and photography. The beginning of their affair coincided with the declaration of civil war in Spain, and her ever-present, anguished iconography testifies to the period’s political climate as much as it does her own stormy character. The famous Weeping Woman (1937) portrait was a direct response to the rise of fascism, and a total of ten paintings and 25 drawings of Maar as the ‘weeping woman’ exist from that year. Maar also painted strokes of Picasso’s widely known war piece, Guernica (1937), documenting the studio evolution of the painting through her own photography.

Maar’s jealousy regarding Walter, and a burgeoning affair between Picasso and Francoise Gilot, led to the dissolution of the duo's relationship, and after their separation in 1946 she suffered a nervous breakdown and was moved to a private clinic at the intervention of the psychiatrist Jacques Lacan. After psychoanalysis, Maar found solace in Roman Catholicism, from which her famous declaration derives: “After Picasso, Only God.” She died in 1997, outliving Picasso by 24 years.

Françoise Gilot

In 1943, Picasso met the handsomely featured Françoise Gilot, a fellow painter, who, at 21, was 40 years his junior. After three years together she gave in to Picasso’s entreaties to live with him – the first time he had lived with a lover since his marriage to Khokhlova – and the pair moved to a disused perfume factory in Vallauris.

Picasso did not paint Gilot through realistic portraits, instead preferring to use vegetal elements of nature to depict her – the stem of flower, for instance. A son, Claude, was born in 1947, their daughter Paloma following in 1949, and in spite of artistic concessions to his affiliation with the Communist Party, the majority of Picasso’s paintings from this time were focused on family life. As time passed, Gilot remained dedicated to her own art, and although she was reportedly a fond mother, who also depicted her offspring in her work, a number of Picasso's family paintings portray her as disengaged from the children playing at her feet.

Unlike the other muses, Gilot’s inner psyche felt inaccessible to Picasso in his painting. She was fiercely headstrong, and in 1953 she left Picasso, and moved with the children back to Paris. 11 years later, in 1964, she published Life with Picasso, a telling memoir of their time together; the book was hugely successful, in spite of an unsuccessful legal challenge from Picasso attempting to stop its publication. Furious and betrayed by Gilot's candid account of their relationship, Picasso refused to see Claude or Paloma ever again.

Gilot moved to America to try to escape Picasso’s orbit. In 1970, she married Jonas Salk, the scientist who invented the first polio vaccine, and remained with him until he died in 1995. Now 94, Gilot has enjoyed a fruitful painting career, as well as publishing numerous books and articles, and working as a teacher.

Jacqueline Roque

in 1953, Picasso met the striking Jacqueline Roque who was working in a pottery shop in Vallauris. She was 26 and Picasso 71, but he is said to have wooed her by drawing a dove on her house in chalk and bringing her one rose a day until she agreed to his taking her out. They married after Khokhlova died in 1961 and stayed together for the remainder of the artist's life. During this final chapter, Picasso made an extraordinary variety and number of works, many of which have perplexed critics. Roque was used as a model and muse, but often her face is not recognisable; Picasso’s interest in the aesthetic of African art and the power of the imaginary distanced him from focusing on specific resemblance or historicity, and so Roque’s identity as an individual came secondary to the abstract figure signified in the picture.

Picasso continued working endlessly in the last years of life in an anxious and obsessive manner, often repeating the same styles and subjects. His representations of Roque are prolific, perhaps outweighing the number of works made about Maar. In 1963, he painted her portrait 160 times, and continued to paint her, in increasingly abstracted forms, until 1972. By understanding the notion of the ‘model-muse’ as both figure and concept, Picasso’s paintings sought to transcend the particularities of their cultural formation as representations in the history of art. Roque looked after Picasso’s estate after his death in 1973, fighting with Gilot and her children, and preventing them from attending the funeral. Eventually, Gilot and Roque agreed on establishing the Musee Picasso in Paris. Roque killed herself in 1986.

Picasso: The Artist and His Muses is on show at Vancouver Art Gallery until October 2, 2016. The accompanying book is out now, published by Black Dog Publishing.