“On the surface, New York in the early 1980s was a shit show,” says Liz Lamere. “High crime rates, homelessness, the AIDS crisis, severely limited resources. But this environment spawned a vibrant cross-cultural community in the art, music and fashion worlds. People created by any means available.”

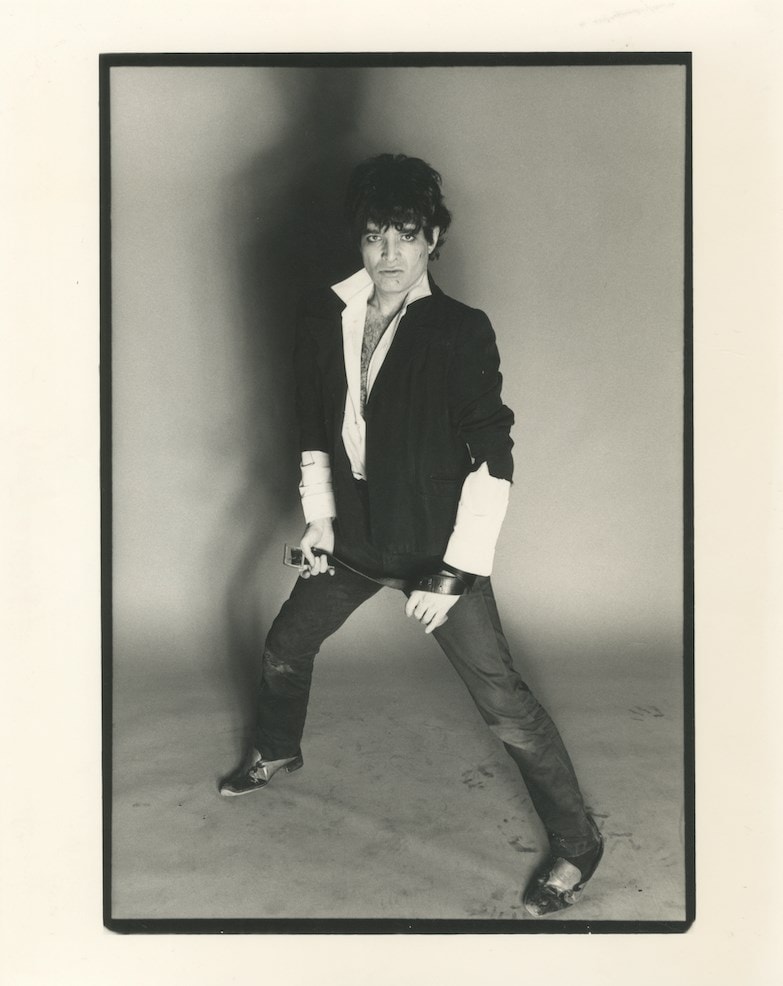

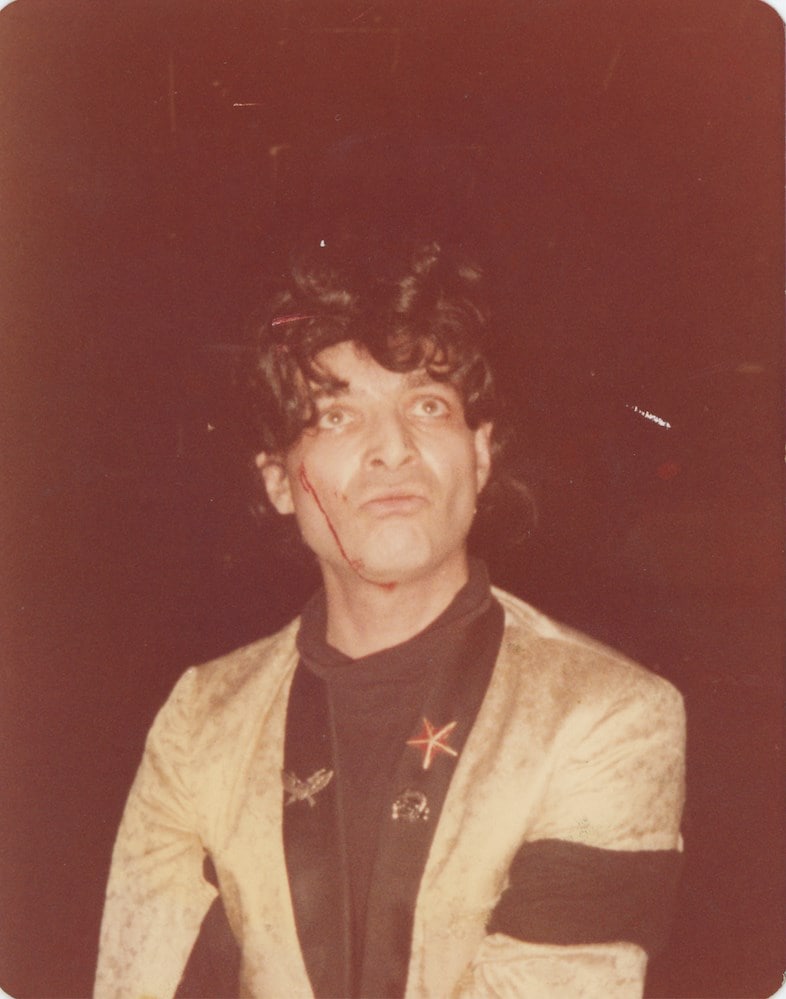

One such person who was finding his singular creative spark amidst the volatility was Lamere’s partner, the late Alan Vega, one half of the pioneering electronic-punk outfit Suicide. After the group’s 1977 self-titled album – a raw record filled with grinding drum machines, haunting organ, feral screams and ghostly atmospherics – but before their more polished follow-up in 1980, Vega wanted to do some solo stuff. “He had some different sounds that he wanted to mess with,” recalls Phil Hawk, a guitar player that Vega began collaborating with after they met at a show at Max’s Kansas City. “He was very much in the mindset of, ‘I don’t want this to be another heavy electronic thing.’”

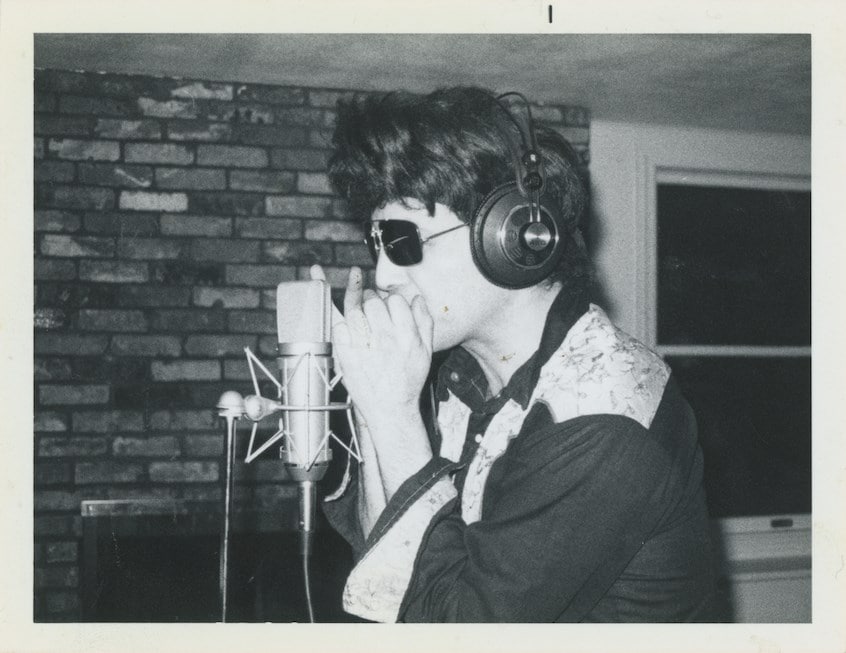

The result of this collaboration was the 1980 record Alan Vega, a stripped-back affair which incorporated more influences of classic rock’n’roll, blues and rockabilly. Its propulsive lead single, Jukebox Babe, almost recalls an old Elvis cut, complete with doo-wop finger snaps and blasts of harmonica. In fact, it was Hawk seeing Vega perform for the first time that led him to think he was watching a “blonde Elvis”. At that very same show, Frank Zappa happened to be in attendance too. “As soon as Alan started his set, he made for the door,” Hawk says with a laugh.

The artist’s eponymous album, Alan Vega, along with his 1981 album, Collision Drive, have now been remastered and reissued from the original tapes and are available on streaming platforms for the first time. “He would be very happy to have these records re-released,” says Lamere. “He loved the freedom of the blues and rockabilly and the nuances these styles opened up in his voice.” It was significant for Vega to have a vehicle outside of Suicide, a band who were feared, loathed and adored in equal measure and could turn rooms into riots via their ferocious assault. “Alan’s solo music career was very significant to his evolution as an artist,” she explains. “While he believed the music he was creating with Suicide was groundbreaking – and the initial extreme negative reactions to it served to him as a strong indicator that they were doing something important – to be true to himself as an artist, he needed to have an outlet for his independent expression.”

“I’ll never retire. It’s not in my blood. I’ll die dancing. I’ll die right on stage” – Alan Vega

Despite Vega’s status these days as a true innovator and agitator, Suicide was far from a commercial success. “He had no visible means of income,” recalls Lamere. But New York was a playground for Vega – Lamere remembers him making light sculptures from recycled materials he found in the streets. Vega was born and died in the city, and it played a crucial role in shaping the mood, pace, tone and energy of his artistic pursuits. “His music was the auditory counterpart to his visual art and its energy and intensity reflected the city that was always his home,” says Lamere. “For Alan, all forms of creation, in any medium he could get his hands on, were pure catharsis and essential. The city, life, the universe, was all his muse.”

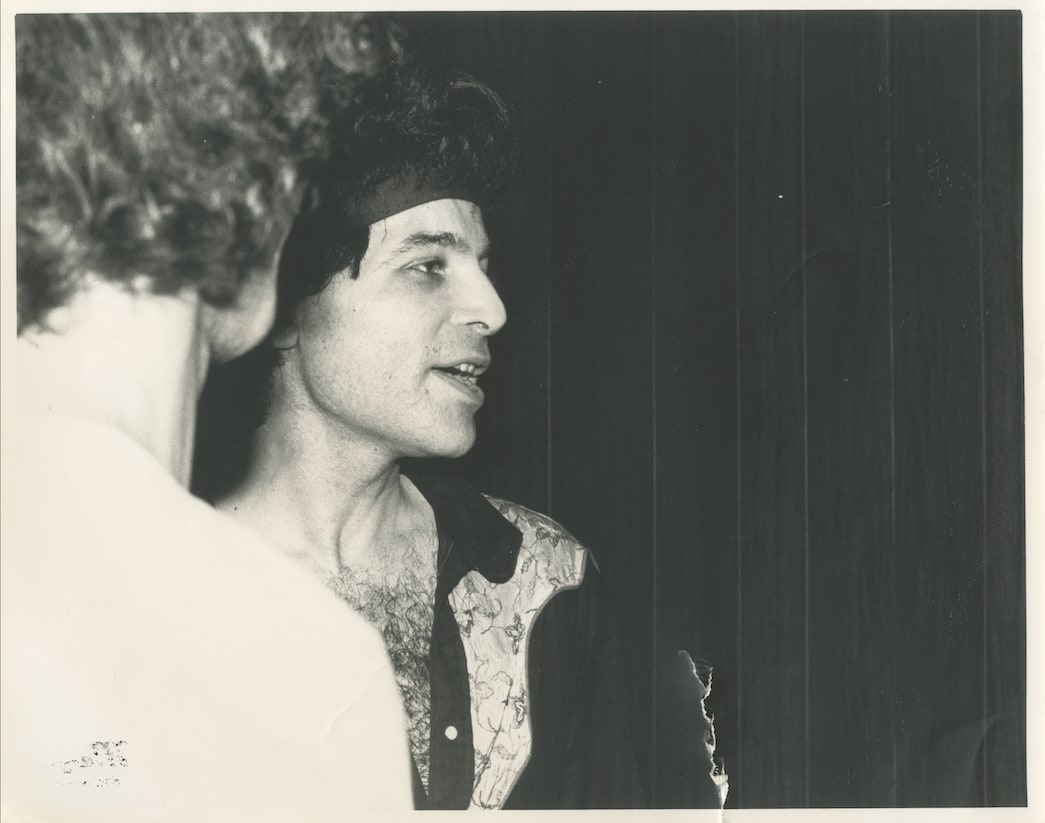

For the first solo record, Vega acquired a loft space in the downtown financial district where he and Hawk would work on songs together. “There were businesses in the building, so at night they just turned the heat off,” recalls Hawk of the icy temperatures. They drank black coffee and sipped cognac: “Back then you had to call from a pay phone a block away,” he says. “And then you would walk the block and he would throw the keys out the window, usually in a sock. The elevator door would open and every time, without fail, there was Alan – he would always give me a big hug and a kiss.”

Their musical setup was primitive. “It was very limiting,” recalls Hawk. “He had a rhythm machine and a couple of effects pedals, and I had a guitar and amplifier, so we didn’t have a lot to work with. But it worked.” They toured the album together briefly, had a hit in France with Jukebox Babe, and spent the summer partying and playing with Billy Idol, before Vega went on to work with other musicians on his next solo album, Collision Drive.

Suicide would wind things up after the release of their second album, before returning in the 2000s to a hero’s welcome, and a legacy that has seen them help shape the careers of everyone from Nick Cave to Bruce Springsteen and LCD Soundsystem. Vega remained a prolific artist, knocking out a steady stream of solo records and collaborations before his passing in 2016. When I interviewed Vega less than a year before his death, having suffered a heart attack and stroke a few years before, he had no plans to stop creating. “I’ll never retire,” he told me. “It’s not in my blood. I’ll die dancing. I’ll die right on stage.”

While Vega was an artist with a firm view on the horizon, Lamere feels that having these out-of-print records back in circulation is crucial. “In his final years he was happy to hear that his work continued to be discovered by new generations and remained influential,” she says. “He would be genuinely touched by how much access people have to his music now and by how beautifully relevant it remains.”

Alan Vega (standard and deluxe editions) and Collision Drive are out now on Sacred Bones.