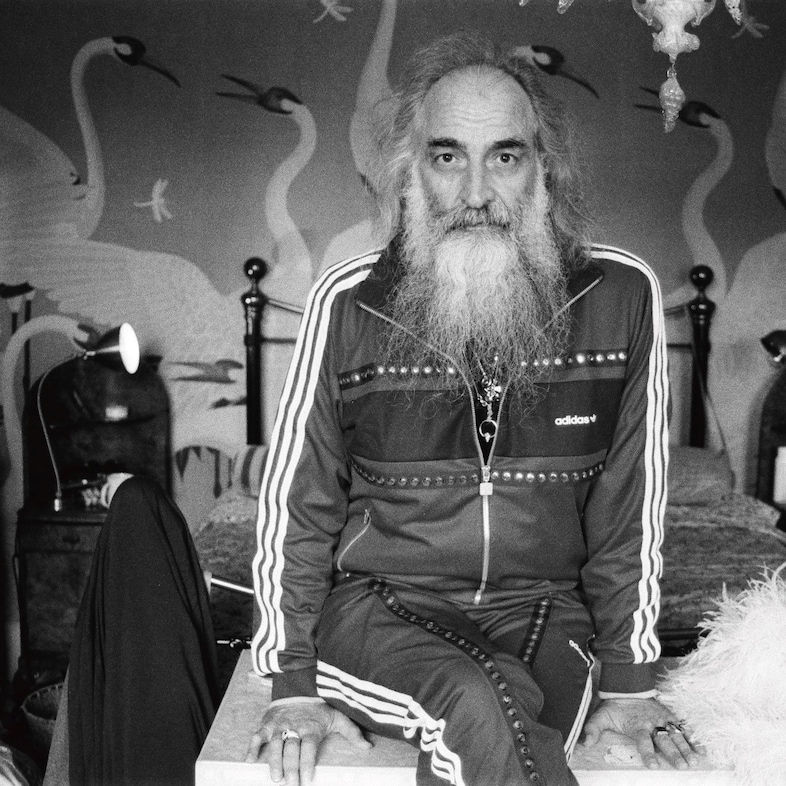

For the Bad Seeds musician and composer, trekking out to a wildlife refuge in Sumatra for Ellis Park brought him face to face with ghosts from his own past, and the healing act of creation

Warren Ellis credits his ability to sink his teeth into an idea as the secret of his decades-long creative partnership with Nick Cave – though Cave likes to joke it’s because he was “fun to take drugs with”. It’s a stubborn trait the musician shares with Femke den Haas, an animal rights campaigner based in Sumatra who runs a rescue centre for abused and trafficked animals. In the early days of Covid, the composer and Bad Seeds/Dirty Three talisman was looking for a way to “put something back”.

A friend hooked him up over Zoom with Den Haas, who needed funding for a site tending to creatures unable to return to the wild, and the seeds were sown for Ellis Park, now the subject of a new documentary by Justin Kurzel. It’s a quiet miracle of a film, held together by threads of shared love and devotion, in which Ellis comes to terms with his difficult past while visiting his ailing parents in Ballarat, Australia, before making the trip to meet Den Haas for the first time in Sumatra. “I went there thinking we were making a film about animals,” says Ellis, who can be seen serenading a clan of meerkats in an exclusive clip from the documentary below, “but I forgot how extraordinary human beings can be, when they move forward with love in their heart.”

Alex Denney: How did you first connect with Femke about doing the park?

Warren Ellis: I was introduced to Femke by a friend during lockdown. I was looking to do something and I didn’t know what, but I think I’d arrived at a point in my life where I wanted to put something back. Femke and her team are some of the most extraordinary human beings I’ve ever seen. We get a lot of information now about how fucked we are as a race, and it’s good to be reminded that we have the potential for good as well as for evil, you know? Because we can lose sight of that. Femke’s motivation is selfless; she doesn’t do it for the accolades. I see her as this shining [light], mainly because she just gets down and does the work.

AD: How much of your decision to help out came down simply to her as a person?

WE: It really boiled down to a few things. I saw a photo of a dog whose bottom jaw had been broken so it was hanging open. Femke had picked it up off the street; they’d taken it in and tried to heal it. It was one of the most devastating pictures I’ve ever seen. Another photo was of Rena, the monkey without arms; I saw a series of photos of her from when she’d been handcuffed under the table of a trader, and she’d been eating away at the skin down to the bones to try and get free, and the guy was just dousing her in petrol. It was this absolute horror scene. They made the difficult decision to cut her arms off, and [now] you have this amazing little character of a primate, who, despite what she was up against, just barrelled through. And I was really moved. I met Femke over Zoom and knew within the space of 30 seconds that she was for real. It was never meant to be public. I just thought I would donate the land and they would deal with it. And then we realised, after we got the land, that we had to build the sanctuary. So that was when I decided to go public with it. I guess it’s an Australian thing of not wanting to stick your head up high, you know? Like tall poppy syndrome, they like to smash it down.

AD: Like Bono, on his shining horse.

WE: Yeah, I mean, I did the film so I could raise awareness of what these people are doing. And there’s a narrative there that is very easy to [misinterpret]. But, you know, fuck it. I know why I’m doing it. If I’d had any understanding of what was involved I probably wouldn’t have done it, because I really had no clue. But I think my naivety has been my greatest weapon in my creative life, because I’ve never been put off anything.

When I eventually met Femke [in Sumatra], it was so rock and roll. It really reminded me of when I hit the road with Dirty Three in the 90s, and we were literally running on the smell of nothing, just sheer belief in what we were doing. But she was doing a much wilder thing than we’d ever done. It’s dangerous work out there, because you’re interrupting the work of animal traffickers. There’s a lot of money involved; it’s comparable to the drug trade. So if you interrupt that they come looking for you. They’ve had shots fired at them – they had a big bust of 1,500 animals and had to get security in at the sanctuary, because they were worried about retribution. It’s way more dangerous than playing in a kind of marginal indie rock band. [Laughs].

AD: There’s a moment near the end of the film where you tell Femke you love her, which I thought was so touching for someone who you’ve just met, essentially.

WE: Well, we had just met but, you know, it’s very similar to the collaborative relationships I have with the people in Dirty Three or with Nick and the Bad Seeds. There’s this thing when you create together where you’re engaging your heart towards the same end, and that requires love. In my mind there’s some love needed there, a cosmic kind of love or something. And I see Femke as a real collaborator. How you define that love is incredibly personal, but with any creative act that I’ve done I have to fall in love with whatever it is I’m doing, like I feel it in my stomach. That’s what makes me act on an idea.

AD: To me it feels like the film draws a lot of its power from the way it suggests these connections.

WE: Yeah. I mean, I’m someone who will die trying to get every idea over the finish line. That was the thing Nick and I had in common when we met, although he says it’s because I was fun to take drugs with. [Laughs] It’s the belief in the idea that’s important. For [Ellis Park] we had a loose idea, but most of it isn’t in the [edit] because the film was found in the actual shooting. It became this confluence of narrative streams that comes together when I head to the sanctuary, [because] I don’t even think I knew what going there was all about for me.

AD: That’s the magic of the film, I think. The deeper resonances only become clear through the telling of the story.

WE: The film actually arrived at a pretty crucial time in my life. I was going through a separation; I’d just met somebody and fallen in love. I was going to the sanctuary. My dad was dying. Had cancer, mum had dementia. All this recurring stuff from my past that I’d avoided, this element of violence in my childhood, all of a sudden came up. It all kind of reached a peak. I was on tour doing Carnage and they had a fucking camera on me the whole time it was unfolding [for Andrew Dominik’s tour documentary This Much I Know to Be True]. And I had to be this responsible person doing the tour, you know, but inside I was just caving away, and then coming back from Sumatra, I had a nervous breakdown. So, in between Sumatra and me being back in the studio, there were these six months that were the darkest night of my soul, and I’ve worked through that with the help of a psychiatrist and antidepressants. So it was a strange time for it to be going on, [but] I guess you never know when those things are going to happen.

AD: It’s a beautiful thing to come out of it, though. For you personally as well, I imagine.

WE: I can’t look at it. I mean, I can’t watch it and present it [at festivals] because I can’t really talk afterwards. I tried that once and it was too difficult. But I’m happy to talk about it without seeing it, because I just don’t feel as vulnerable for some reason when I do that. But I really love the fact that the audience is experiencing all that stuff for the first time, and seeing this extraordinary team of people doing seemingly God’s work. I went [out to Sumatra] thinking we were making a film about animals and the park and forgot how extraordinary human beings can be, when they move forward with love in their hearts. But I mean, I’m 60 now and this is stuff that, if you’d said I’d be saying this 20 or even five years ago, I wouldn’t have believed you. But it’s just kind of the way I feel about things now. It’s something I’ve had to grow towards.

Ellis Park is out in UK cinemas now. More details on the sanctuary, including how to donate, here.