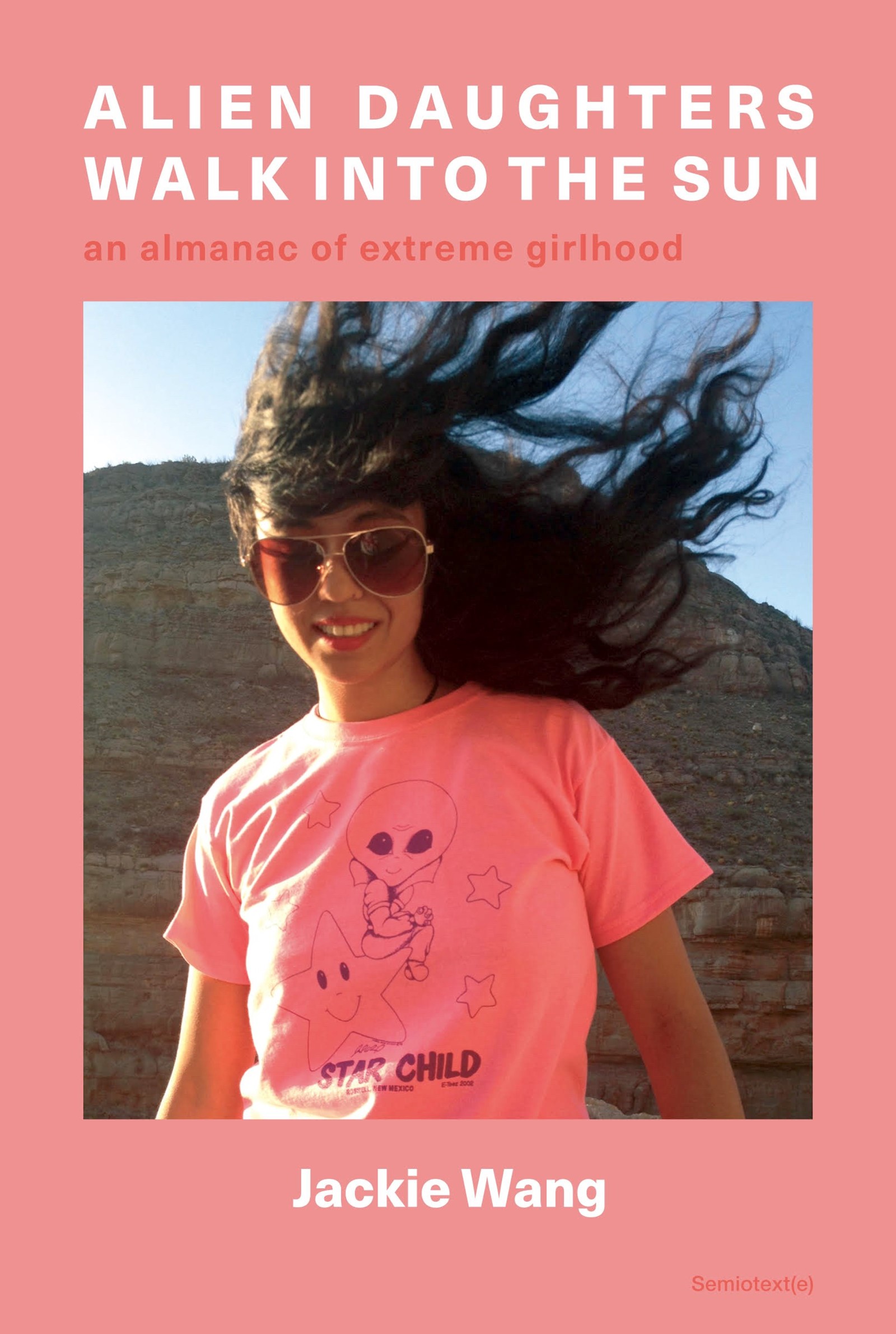

“I think you are going to make a huge book. An almanac for extreme girlhood,” author and poet Bhanu Kapil wrote via email to Jackie Wang in 2011. The message was, in short, prophetic. This fall, Wang fulfilled Kapil’s prediction with Alien Daughters Walk Into The Sun: An Almanac of Extreme Girlhood, published by Semiotext(e).

Kapil’s words of encouragement were the collection’s ideological genesis, Wang tells me via Zoom, which is why she included a screenshot of the email in Alien Daughters’ first page. The book is a rich and radical amalgamation of the National Book Award Finalists’ work, spanning from adolescence to adulthood. When reading, I’m not only struck by the sheer volume that the Carceral Capitalism and The Sunflower Cast a Spell to Save Us from the Void author excavated – a process that took nearly eight years to complete – but also by the beauty and profundity with which Wang writes even during her early years (or rather, in her girlhood).

From introspective handmade zine excerpts to Tumblr blog posts on gender politics, to literary magazine pieces, interspersed with vignettes of Wang’s modern reflections and commentary, readers are privy to the writer’s uncensored, unfettered first draft of a prolific artistic life. Like a hulking, true almanac, the book is organised by the location in which the work was written rather than being explicitly chronological, though readers sense that each place acts as a simulacrum of Wang’s movement through time and intellectual maturation.

Wang sees Alien Daughters as feminist autotheory and autocriticism, invoking writers like Maggie Nelson and Chris Kraus, her editor at Semiotext(e), among others. The work is, above all, a treasure chest of passages and essays, a map where Wang takes you alongside her psyche as she traverses continents, unspooling her thoughts and unravelling our understanding of the world as we know it as she goes.

Below, Jackie Wang tells us more about the creation of Alien Daughters, unpacking the internet, and her guileless youth.

Madeline Howard: What was the experience of collecting this archival material like for you?

Jackie Wang: It was a multi-year sifting process. I had assembled some of this material for a memoir class I took in grad school that was taught by Jamaica Kincaid. But I was a hot mess and had a nervous breakdown that semester. I submitted this crazy, messy document late, so I don’t begrudge her for giving me a B-plus. But I think that was when I actually started thinking of this project as a potential collection.

I originally thought that I would organise it into an encyclopedia of entries, so I was trying to figure out a structure based on key terms. Ultimately, Chris [Kraus] and I thought it was too disorienting to jump around in time. Then, I organised it chronologically, but the first draft got thrown away. The printed 900-page manuscript was on my library carrel on the Harvard campus, and my desk expired, but I didn’t get notified because the notification went to my spam mail. I got there one day and all of my papers were gone, so I had to start from scratch. It almost felt like the book that would never be finished.

MH: You write that while you don’t agree with all of your older writing, you can’t disavow it, because you respect the person you used to be. Can you speak more on this? For me, I find my younger self embarrassing.

JW: As I was editing the book, I went from feeling mortified and embarrassed, like, “Am I really gonna publish this?” To saying, “This the best book I’ve ever written!” And it was for this reason that you pointed out. When I was younger, I was guileless. There was this openness to the world. Now, I feel a little bit hardened by academia and the struggle to survive financially. That said, I’m still basically the same. But there was a real lust to absorb everything then. Now, I’m a little bit more cautious. I think that happens when you have something to lose or a reputation to protect – you start to doubt yourself.

What I miss most is that I felt so free in my soul. A lot of it had to do with the process and pure joy of writing, and just trusting the writing will take you where it needs to go. I remember the ecstatic flow state that I would fall into. For me, writing was never goal-oriented. I liked the process of metabolising subjective experiences through writing. I felt like I never really lived or understood anything until I wrote about it. Now, I’m like, “What’s this publisher going to think of this? What will my agent think?” It’s a layer of mediation that can make you feel frozen and stilted. It’s very hard for me to break through that reservation that’s built up in me over time.

“I liked the process of metabolising subjective experiences through writing. I felt like I never really lived or understood anything until I wrote about it” – Jackie Wang

MH: What is your writing process like now?

JW: My process is that I still write mostly for myself. I’m a diarist. Writing privately has to do with also feeling like it’s treacherous to be out in public all the time. There’s basically a ten-year lag between when I start working on a project and when I realise that what I’m working on is a book. Usually, I’m just obsessively collecting quotes, writings, fragments, meditations, and not even thinking that it’s for anything. It’s almost like I have to go behind my back to get writing out. I find that when I know it’s going to be for something, it makes the process a torment.

MH: Your work feels inextricable from the online spaces that radicalised you. Was the internet essential to your education?

JW: I distinctly remember when I got the internet and how it rocked my world in middle school. If you’re a freaky person who doesn’t fit in with the people around you, getting the internet allows you to plug into spaces that would otherwise not be accessible to you. I remember a whole world of indie music and anarchist politics opening up to me when I got the internet, and it was completely exhilarating.

When I graduated from undergrad, it was like the golden era of small press feminist literary blogs. A lot of writers I was in correspondence with on blogs are well-respected today, like Kate Zambreno, Anne Boyer, Ariana Reines, Dodie Bellamy. We loved books and wrote long, thoughtful essays on our blogs about books, and then we would reference each other’s posts in our posts. It was a beautiful community that only existed for a very small window of time.

“I still write mostly for myself. I’m a diarist. Writing privately has to do with also feeling like it’s treacherous to be out in public all the time” – Jackie Wang

MH: In today’s internet culture, it seems that (besides Substack) ideas are spreading through video-based mediums. What do you make of this?

JW: Even when I was on Tumblr, it was actually not a natural fit for what I was doing. The content of what I was writing wasn’t very aligned with the Tumblr aesthetic, which was a visual platform that we were using almost like text-heavy WordPress, writing about the politics of trauma and gender.

MH: How was your internet education different from receiving academic institutional support?

JW: I find that the academic knowledge production model is so hierarchical and grindingly slow, and actually designed so that it’s inaccessible because it’s paywalled unless you have institutional access. I find it really frustrating and wish I could go back to posting my essays on my blogs. But I’ve had problems where I’ve posted early drafts of articles on my blog, and then when I’ve tried to publish them in academic journals, they run it through the plagiarism scanners, and since I posted on my blog, it’s not eligible to be published anymore. It just makes me scratch my head because I’m like, “Why wouldn’t I share something that I’m working on with people?” I never had a proprietary relationship to my work or what I produced.

Alien Daughters Walk Into The Sun: An Almanac of Extreme Girlhood by Jackie Wang is published by Semiotext(e), and is out now.