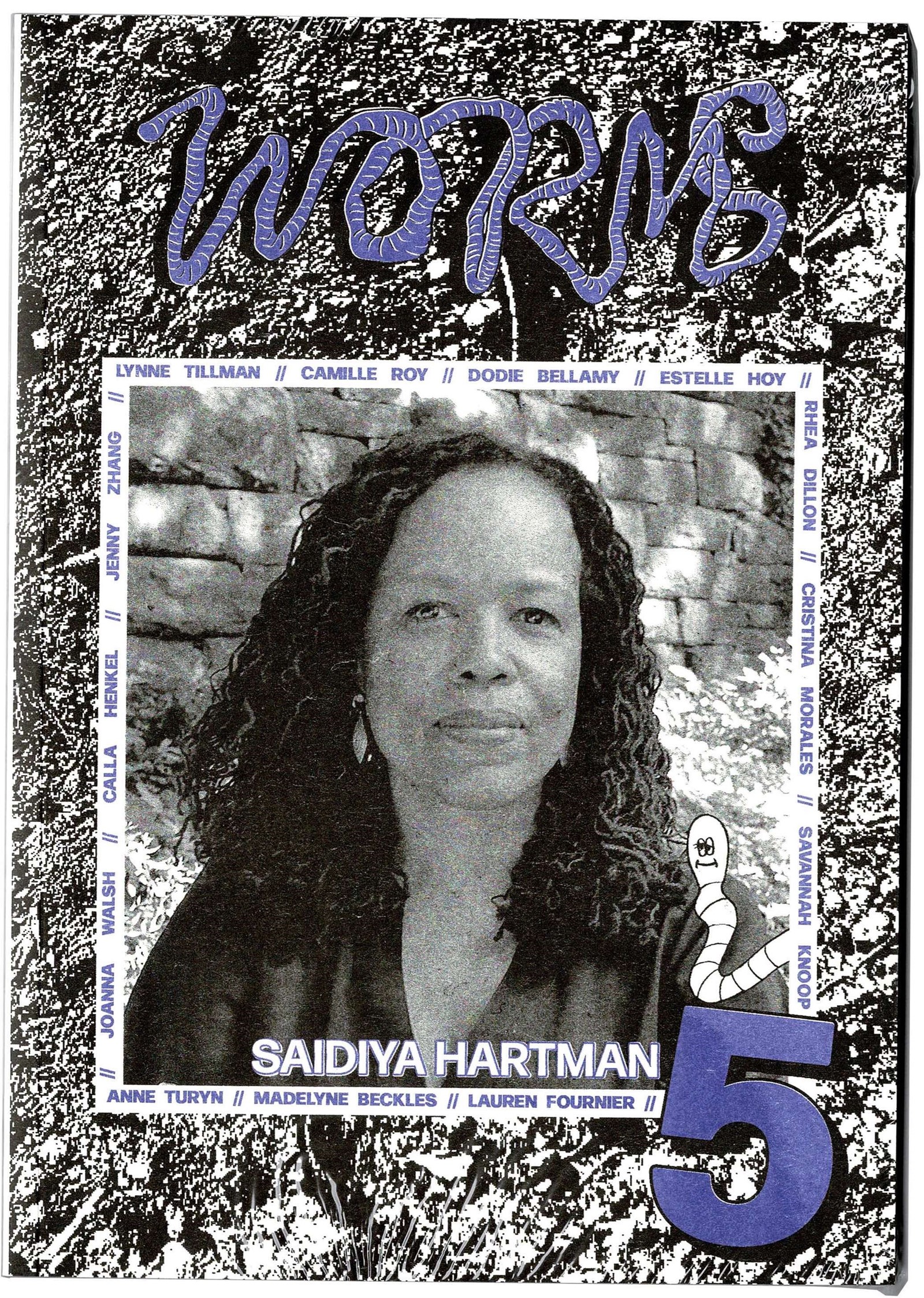

The following excerpt is taken from the fifth issue of Worms Magazine, a London-based print magazine focusing on female and non-binary writer culture. Titled the ‘impurity’ issue, Worms #5 focuses on writers that steal, are sexually explicit, and mix high and low culture in their work – the issue features conversations with Saidiya Hartman, Camille Roy, Savannah Knoop, Calla Henkel and more.

The following interview – between Worms founder and editor Clem Macleod and New Narrative writer Dodie Bellamy (author of Cunt-Ups and When the Sick Rule the World) – covers the art of the impure, ‘literature barf’ and what it means to be female and feral.

Clem Macleod: Hey Dodie.

Dodie Bellamy: Hey Clem. I like to see that your background is messy too. That makes me feel good.

CM: I’m actually at the ICA right now because I do fortnightly events here where people come and write.

DB: It sounds fun.

CM: Yeah, it’s really fun.

DB: I want to start taking classes that other people are teaching just to see how they do it. I teach privately, but the people that I teach are all professional artists and curators that want to learn how to do creative writing.

CM: That sounds like me leading these workshops. I’m like, just write about the dog shit that you stepped on on the way here.

DB: And then do they read it out loud?

CM: Some people do, yeah. We’ve got a synthesised mic because we didn’t want it to be scary for people to read out their work. So if people want to, they can literally hide their face and just talk into the mic, and it will just sound like garbage, but in a good way. I think it’s a good way to practise, and then it’s a good way to just get people writing. I get my friends to come sometimes who don’t write. They’ll be like, I’m really dyslexic and I don’t know what to write about. And I get them to come, and they always end up writing really amazing stuff. When you don’t have the inhibitions of what writing is meant to look like, it just comes out so much better.

DB: I took a class with Diane di Prima, a poetry workshop, and it was all these women who had never been published but had been working with her for years. And so it was all this writing, these prompts and writing in class, and they were fantastic at it because that’s the only writing they did. I would do mine, and then Diane would never praise me, because I wasn’t good at it. It was really funny.

“This whole idea of expulsion is funny because I’m one of the most anal, obsessive writers that you could get. I mean, it takes me forever to write anything” – Dodie Bellamy

CM: Maybe you should come and host one of our EarWorms events.

DB: I would love to.

CM: It’d be so nice.

DB: Groups just need a leader, it just takes away all the power dynamics. That function is really important.

CM: I wanted to start by talking about how you found yourself seeking a literary barf or an ‘art of the excess.’ Also, maybe you could summarise your Barf Manifesto for the Worms readers?

DB: I’m riffing on Eileen Myles’ piece Everyday Barf, and it ends with them on a ferry to visit their mother. There’s a lot about mortality in it. Then one person gets sick on the ferry, and then the entire ferry is throwing up. I use the barf as a metaphor for writing. Rather than everything being this kind of rational, linear focused thing to bring in all these different layers. But this whole idea of expulsion is funny because I’m one of the most anal, obsessive writers that you could get. I mean, it takes me forever to write anything. In my own work I bring all that in, on the surface I’m trying to make it look less controlled.

CM: Like a bulimic barf rather than a food poisoning barf?

DB: Yeah maybe (laughs). Where you sit down and you have your ice cream and your pastry and get ready (laughs). Yeah, a controlled bulimic barf. Yes. I’m currently trying to write a grant for a book proposal, and I don’t think that far in advance. I’ll know the topic. I know what I want to write about, but then I don’t have this plan ahead of time. It’s more like the plan will emerge, and I just allow myself to keep bringing in layers and layers, and not every layer will end up in the final piece.

CM: I was drawn to the bit in The Barf Manifesto where you say that the last time that you taught Everyday Barf, a paralysed woman in a wheelchair said people don’t want to think about the body because it reminds them of their vulnerability. I've been reading a lot about shame, female shame and all of these ideas around how a woman should be and how a woman should act and the idea of the ladylike, which I feel was so something that used to be pushed on me growing up, and I was so the opposite of that.

DB: Oh yeah, I got criticised a lot for not being ladylike.

CM: Yeah same. I feel like now, for my generation, it's way more acceptable to dress a bit feral and not shower if you don’t want to.

DB: As long as you look like you’ve done it.

CM: What do you think writing about these things that we were supposed to be kind of ashamed of does to our view of them personally?

DB: I think that’s always been an imperative of mine, to write about all of these things, and I think that’s where the political comes in … to write about people and bodies who haven’t been considered worthy for literature before. I teach in this class called Sex and Death at California College of the Arts. We were talking about women and sickness. I didn’t assign them to read The Sick Woman Theory by Johanna Hedva, but I brought it in and I was reading this part where she talks about the sick woman being anybody that’s a freak or on the edges of culture, or marginalised because of race or illness or sexuality, you know? And so the sick woman kind of encompasses everybody who’s not this mainstream, cis white, hetero male, you know blah, blah, blah.

And I teach this too. I think you need to push yourself to the edge of discomfort and that can generate a lot of energy. It creates arrows to the writing. It’s funny – before I was a writer, I was living this kind of feral working class life. And in a lot of ways I’m much more constrained now than before I became a writer because the writing and art world, at least for my generation, is so fucking bourgeois. It's like you’re suffocating in it.

CM: What is considered feral in your opinion?

DB: Anything to do with the female, the body, the barf. It’s not very hard to be female and be feral. I think it’s really beautiful that so much more is considered acceptable to write these days. There’s presses that are publishing a wide range of experiences and gender expressions.

CM: Do you think that it was this idea of the impure or the feral that brought the writers of New Narrative together?

DB: Yeah. I always associate this interest in the feral with women because it’s much more of a struggle for women to get there than men. The New Narrative movement was mostly gay men who were having lots of promiscuous sex. They were already kind of pushing this whole culture that was pre-Aids that was really pushing boundaries of sexuality and the body. So I think there’s an imperative to write about gay sexuality to make it visible, you know. I think things have changed so much. I think it’s really hard for people to remember that it was radical to talk in public about being gay at a certain point, you know?

“Before I was a writer, I was living this kind of feral working class life. And in a lot of ways I’m much more constrained now than before I became a writer because the writing and art world, at least for my generation, is so fucking bourgeois” – Dodie Bellamy

CM: So it was more this idea of inserting the personal into the writing than it was necessarily about the feral.

DB: Yeah. I don’t know. There was this whole political group movement. When women talk about the feral, it always feels like this lonely, abject thing about their own body issues. Right? I don’t really like talking in broad strokes about culture in people.

CM: There’s a bit in your biography that says that when you were 27 and still involved in Eckankar and you first moved to San Francisco, you were told that you were the most insecure person that people had ever met. And then you started writing shortly after. Do you think that writing about these intimate parts of your life helped you come to terms with them?

DB: Probably. I don’t know how much intellectualising has changed anything though. I don’t know if intellectualising makes a change in anybody’s life. But I do think that writing has been sort of transformative; writing a piece where you sit and obsessively edit and craft it, is more transformative to me than journal writing. There’s something about taking that experience and transforming it into something else that doesn’t happen in journal writing. I do think it has helped me come to terms with a lot of things. But I still feel, you know, like I should be together and I’m old and I’m just as fucked up as I ever was. So I'm kind of frustrated by that.

CM: I wanted to talk a bit more about your book Cunt-Ups and the riffing off of William Burroughs, seeing it as like a kind of feminist reclaiming of the gesture of the cut-up. What compelled you to do that?

DB: I was doing my first teaching gig in the mid nineties at the San Francisco art Institute. And I was teaching this undergrad class called Prose, which was ludicrous because undergrad art students do not know what that word means, or at least back then they didn’t. I came to collage via the Kathy Acker route, so it’s a very intuitive process. I’d been doing lots of collage. I was kind of scoffing at the cut-up because it was so formalist. But then I assigned some of The Third Man by Burroughs and got my students to do cut-ups and I was really impressed with what they did. So the semester ended and I was on winter break and I had a month to write concepts for this new book. Basically, I was inspired by what the students did. I loved the idea of bringing in other texts and the way they would work against each other.

CM: What was your involvement with the Mirage publication? Why was this important?

DB: Well, first of all, Kevin (Killian) started that publication. So I wasn’t involved with it until it became the zine. I worked on some of the covers. It no longer is, but in the eighties, when I got involved in the bay area poetry scene, it was the centre of small press publishing in the states. One of the things that people did in terms of literary movements like New Narrative and the Language Poets and other groups, was to have a magazine and write about other people in the movement.

So suddenly I’m this young writer, (young in terms of sophistication and experience) and suddenly I’m expected to write essays about other writers around me. I was totally terrified because my only model was a college literary essay, which was always a terrifying form for me. I can write a whole book of crazy shit, but when it comes to writing a straightforward art review for Artforum, it almost kills me. Just having to put my thoughts in that container. I don’t know why. You would think that would be easier.

CM: It’s so restrictive and it’s so much easier writing like you would talk or tell a story.

DB: And also what’s permissible and what isn’t permissible. How much of yourself do you have to dampen in order to fit the form? So, I find those things very difficult. It’s funny. So there were a number of magazines that were associated with New Narrative.

CM: What were they?

DB: There was one called Ottotole that Michael Amnasan started. Soup that Steve Abbott did, and then there was another one that was not really New Narrative, it was more gay-focused. What was that one called? No Apologies. There were other gay writers that were associated with New Narrative, more through friendship than them being part of the group.

CM: How was the movement formed? Was it something that you realised was happening at the time?

DB: I came in as sort of second generation. So I didn’t really have anything to do with the forming of New Narrative. There was lots of funding for the arts so Bob Gluck made his living teaching these writing workshops.

CM: Would you say that Robert Gluck started it then?

DB: Well there’s various versions, but yeah, him, Bruce Boone and Steve Abbott. Bob taught the workshop. A lot of my ideas about writing came from Bruce, but it was more just one-on-one hanging out. And then Steve Abbot would sometimes teach special classes on literary theory and that would connect people.

“I don’t know if intellectualising makes a change in anybody’s life. But I do think that writing has been sort of transformative” – Dodie Bellamy

CM: And was there a physical space for it?

DB: Yeah, it was a bookstore which was also a small press called Small Press Traffic. Small Press Traffic went through various iterations, but when I got involved, it was in a Victorian building. It just looked like an apartment and the front was the bookstore. Then in the back, there was a room where the workshop happened and then there was an extra room that they would rent out to help pay the rent. There was always a hostile renter that resented everything that was going on. That was their home!

CM: That’s so funny.

DB: So it was very comfortable and it was nice that it was in this apartment, it had a much more homey feel to it than if it were in a boxy, institutional space.

CM: In the workshops that were being taught, what were the core writing techniques?

DB: You know, it is hard for me to remember, usually Bob would bring in something really short and read it and we wouldn’t have a lot of discussion about it. Then sometimes he would give assignments. He would often forget them by the next week because I would do the assignment and then he wouldn’t bring it up. But people would just bring in work and read it. It was free because it was funded by public funding and Bob got paid for doing it. I took some college writing classes, but the last one I took, it was a lit class on experimental fiction, which I dropped because I realised that the homeless people in Bob’s workshop were more interesting than college students. It was really exciting to have this huge network and all these readings.

CM: Were there many women involved?

DB: No. Obviously it was coming out of a gay male focus, but it was me and then there’s Camille Roy, and then Francesca Rosa and this woman, Marsha Campbell who was schizophrenic, but really brilliant. And we put her in our anthology and she unfortunately died before it came out. I was really hoping that this would revive interest in Marsha and it didn’t. The anthology did huge things for Gabrielle Daniels, but it didn’t really do anything for Marsha. Part of the influx of female participants came from Kathleen Fraser because we were all taking her class on feminist poetics at San Francisco State.

Worms #5 is out now.