As her new film One Fine Morning is released, Mia Hansen-Løve talks about the power of dreams and nightmares, and working with the inimitable Léa Seydoux

Mia Hansen-Løve’s delicate eighth feature could be described as one fine mourning. Never afraid of autobiography, the 42-year-old auteur’s return to French-language filmmaking is a poignant drama loosely inspired by the death of her father, even using the same hospital rooms in which he stayed. Not that Hansen-Løve is a literal translator of truth to fiction. It just so happens that One Fine Morning stars Léa Seydoux as Sandra, a literal translator of non-fiction.

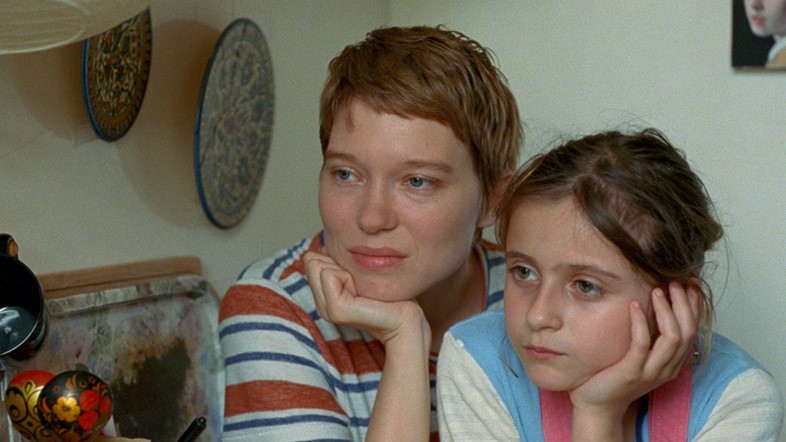

Following Sandra’s day-to-day life, One Fine Morning weaves in and out of how a single mother navigates grief, love, and the existential weight of the world. In Paris, Sandra cares for her young daughter, albeit belittling the child’s adoration of Frozen 2, while visiting her elderly father Georg (Pascal Greggory) in his final days. In between, she chances upon a married astrophysicist, Clément, their mutual chemistry aided by the casting of Melvil Poupaud. As Sandra surrounds herself with books and literature, is she drawn to a romantic prospect who’s into hard science and facts?

“I didn’t want Clément to be in the same field,” says Hansen-Løve. “He’s opening up the world to her, so his job embodies a sense of escape.” We’re talking on one fine morning during the London Film Festival at the Mayfair Hotel. Though Hansen-Løve mostly answers in English, occasionally she uses an interpreter who politely laughs when I refer to Sandra’s job as exciting. “Léa is used to James Bond films and parts that involve costumes,” says the French writer-director. “I was asking for the opposite: I wanted her to look like a real person. She’s no longer the character people look at; she’s the one listening and watching.”

Hansen-Løve’s two previous features, Maya and Bergman Island, both mostly in English, were shot respectively in India and Sweden. One Fine Morning is thus a homecoming. With a logline that may not spark bidding wars for a Hollywood remake, One Fine Morning instead immerses the viewer into Sandra’s routines, whether it’s staring into space on a daily commute, or the gradual transformation of a secret lover into a potential father figure for her daughter.

Hansen-Løve also understands how the passing of time can be cinematic. In Eden, Paul never ages over the years, even when his friends become Daft Punk; likewise, Camille’s maturation in Goodbye First Love is visualised through hairstyles. However, in One Fine Morning, it’s partly due to a shoot that halted several times due to Covid. “I’ve had so many difficult processes in financing and shooting that I can handle interruptions,” says Hansen-Løve. “François Ozon told me he doesn’t love shooting, he loves writing and making films happen. But I love shooting. Even if Bergman Island had to be shot in two different years [due to Greta Gerwig and Owen Wilson dropping out], I actually enjoyed it in the end.”

However, Hansen-Løve wishes to dispel the myth that she’s prolific. “I wrote Bergman Island in 2016, and it took four years until I wrote One Fine Morning.” Even during lockdown, she was unable to bash out another script. “Some directors said they read Proust and wrote four screenplays. But I can’t just write a film and then, immediately after, write another film. It’s impossible!”

Aside from an animated bird in Eden, there are few fantastical moments in her filmography. Yet Sandra dreams of a leopard seal, the creature floating above her bed. Was this a Bergman influence? “In Bergman’s films, dreams and nightmares are integral, whereas, for me, the dream sequence is exotic. Very early on in developing the script, I met this astrophysicist over dinner, and he told me this incredible story of a sea leopard. That night, I dreamed of it, and it triggered in me these weird childhood memories and dreamlike sequences. I think a lot of women tend to dream of this beast devouring you. That gave me the impetus to make him an astrophysicist in the film, and for Sandra to have that same sea leopard dream.” Do all women dream of sea leopards? “Not sea leopards, but snakes and beasts. The dreams are connected with the fear of sex, somehow. Or the fear of men. Fear and desire are intertwined. I remember my mum telling me of dreams of snakes that dealt with both fear and desire.” And men dream that they’re the beast? “Maybe so!”

Along with Sandra’s aquatic reverie, she later remarks that it feels like her father is drowning and she can’t save him. Was this to compensate for the lack of moments like, for instance, Lola Créton swimming at the climax of Goodbye First Love? “I guess all my films have scenes where characters are in the water. A lot of them are about the passing of time, and that’s embodied in the way water is transportative. But I only realised when writing this film how harsh it was on my part to not offer Sandra that chance to be immersed in water.”

Months after Bergman Island’s release, it was revealed in Vanity Fair that Tim Roth refused to swim in the water for a scene; in Filmmaker, another actor called Roth a “total jerk” who made a crew member cry. Has Roth affected whom she might cast in the future? “Tim didn’t fundamentally change the way I work with actors,” she says. “But when he came to the island, it was so far removed from what he was used to – being with a small European team, surrounded by younger women, on this foreign island. It brought in him a fragility, which is probably not the word he would use, but that was enriching for the film. Maybe it’s a superstition, but I think that difficulties on set can serve the film in the end.”

Hansen-Løve laments her long answers when she spots my two pages of questions, most of them unasked. One query is written in red ink, signalling its importance: in Bergman Island, why does Roth write his screenplay on Microsoft Word? “I don’t know how to use Final Draft!” exclaims Hansen-Løve with a laugh. “I didn’t even think of it!” She writes on Word? “I write on this.” She points to a notepad. “I write on a computer as late as possible, and that’s on Word. I find Final Draft personally insulting; it’s like having to swear allegiance to a piece of software that’s specifically for scriptwriting.” She breaks down her least favourite functions of Final Draft’s automatic formatting. “It gives an air of professionalism that’s completely superfluous.”

I admit that I use Final Draft for the reasons she detests it. “I’m sorry!” I tell her she doesn’t have to apologise; I didn’t invent the software. Moreover, Paul Thomas Anderson uses Word, so it evidently works. “When we write on paper, we think differently. On a computer, it’s mechanically going from one idea to another, like dominoes.” The discussion gets so deep, even the interpreter joins in with her own thoughts.

After the interview overruns and I’m leaving the room, the conversation continues. “I’m always trying to postpone using the computer,” Hansen-Løve says as I’m stood by the door. “For me, making films was always a way to escape. I never went to film school – I’ve always tried to do things my own way.”

One Fine Morning is out in UK cinemas now.