As this year’s female-led Venice Biennale continues – themed around Leonora Carrington’s surrealist book The Milk of Dreams – we give you five books to read

This year’s Biennale theme – The Milk of Dreams – takes its title from a children’s book by the surrealist artist and writer Leonora Carrington. Focusing on the changeable definition of what it means to be human, curator Ceclia Alemani has centred this year’s vast exhibition around the book and its transformative, metamorphosing characters. Like Carrington, many of the artists exhibited are storytellers that defy easy categorisation, shifting seamlessly between mediums – a number of whom also orchestrate their imaginative tableaux through the written word. “A novel is a medicine bundle,” the writer Ursula K Le Guin once noted, “holding things in a particular, powerful relation to one another and to us.” Alemani structures the Biennale in a similar way, presenting us with a series of artists and artworks that are powerfully interconnected.

From Carrington’s metamorphic, surrealist short stories to the radical essays of Ursula K Le Guin, here are five books to read before the Biennale.

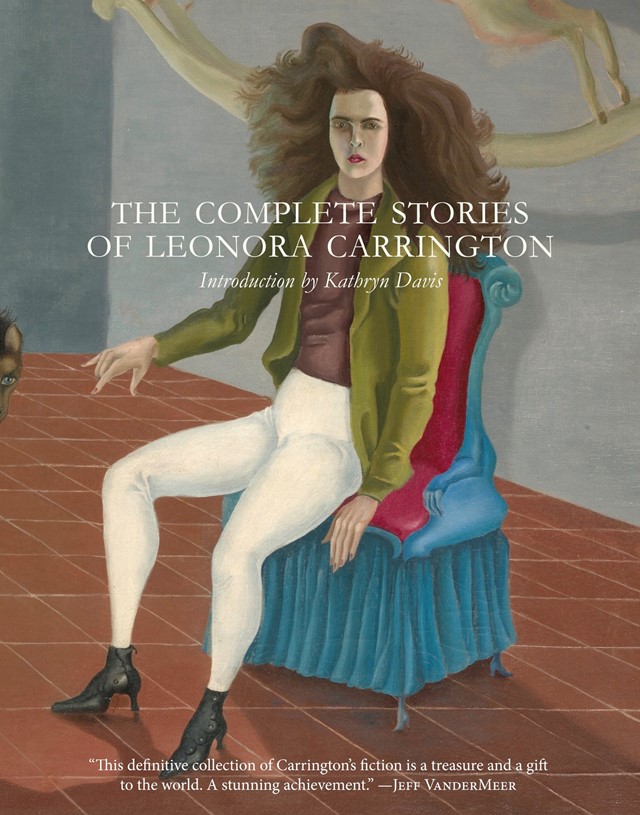

The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington by Leonora Carrington (lead image)

As with The Milk of Dreams itself, Carrington’s short stories are filled with inventive hybrid creatures and moments of unexpected transformation. Take time to immerse yourself in the full fantastical range of Carrington’s creativity; in these stories, a hyena dresses up to go to a ball, a talking horse invites a woman out, and lovers collide under a “mountain of cats”.

New and Selected Poems of Cecilia Vicuña edited by Rosa Alcalá

At this year’s Biennale, Chilean poet and artist Cecilia Vicuña was one of the recipients of a Golden Lion for lifetime achievement. In her site-specific installation, ropes and debris found around Venice twirl delicately as they hang from the ceiling, and Vicuña’s poetry can be read as a similarly captivating, fragmented landscape. In New and Selected Poems, just like the colourful, surreal scenes of her paintings, Vicuña’s writings explore identity and exile, creation and destruction. A central question is always present: “can we go beyond our self’s edge?”

The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction by Ursula K Le Guin

The queen of sci-fi, Alemani names an entire section of the Biennale – one of her ‘Time Capsules’ – after Le Guin and her 1986 essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. In her writing, Le Guin radically reframes and reorients the perspective of human development and history around the collective potential of ‘the vessel’. In response, Alemani brings together artworks by the likes of Ruth Asawa and Sophie Taeuber-Arp; after reading, you’ll understand why. Pick up a purple, pocket-sized edition of the essay by Ignota books, complete with an introduction by A Cyborg Manifesto author Donna Haraway and images by artist Lee Bul.

Nightwood by Djuna Barnes

In another ‘Time Capsule’ section of the exhibition, Alemani features pages from Djuna Barnes’ roman à clef The Ladies Almanack, focusing on her artful illustrations. Privately published in 1928, the work was originally dedicated to Barnes’ partner Thelma Wood. Alternatively, dive into Barnes’ novel Nightwood – a dark, poetic book largely inspired by her relationship with Thelma. For something lighter, try Barnes’ recently re-issued Lydia Steptoe Stories (Faber, 2019). Originally published under a pseudonym, these bursts of voice track the lives of various, restless characters dissatisfied by their limitations – a prevalent theme in Alemani’s exhibition.

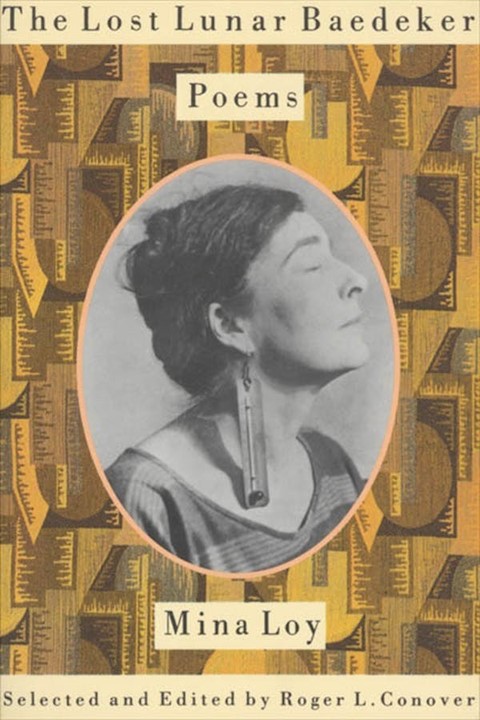

The Lost Lunar Baedeker by Mina Loy

When she wasn’t writing, Mina Loy painted lobster frescos in Peggy Guggenheim’s bedroom in the south of France and designed star-shaped lampshades in Paris. Her poetry however, branded as ‘difficult’ at the time, illuminated the society she lived in with a vibrant ferocity – especially with her repeated calls for women to escape their restrictions and reinvent themselves. Alemani presents Househunting (1950), one of Loy’s mixed-media constructions in the exhibition, and after reading the urgent lines of Loy’s poetry, its title takes on a new significance: “FORGET that you live in houses, that you may live in yourself – / FOR the smallest people live in the greatest houses. / BUT the smallest person, potentially, is as great as the Universe.”