This edition of Girlhood Studies is accompanied by a special curation on the BFI Player, featuring some of the films mentioned in the column – in association with the Seen & Heard season, showing at the BFI this February and March.

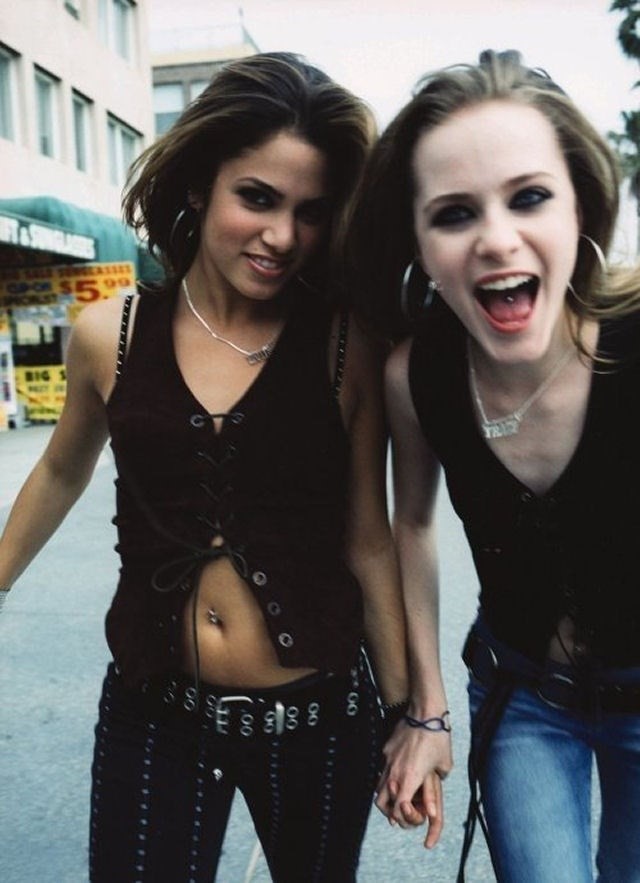

By the time I had been handed Catherine Hardwicke’s Thirteen on DVD, I was about to turn the same age. I remember how we passed it around among ourselves, and talked about it. The film – not that I thought about this much at the time – was one of the few by women directors garnering not only acclaim, but a loaded kind of attention in the early 2000s. It was also the creation of an average teenage girl as much as of its middle-aged director, with 13-year-old Nikki Reed co-writing the screenplay with Hardwicke, a former girlfriend of her father’s, over six days in late 2002. The film stars Reed alongside Evan Rachel Wood, who, unusually for such projects, are actually the same age as the characters they play (unlike, say, the ageless Alexa Demie). Following two seventh-graders who take drugs, shoplift, self-harm and have sex – and the resultant falling-out of the formerly innocent Tracy with her mum – the film accelerates you right into every potential extreme of adolescence, a rush held together by the fact of it being an actual lived experience.

Watching it now, I realise how much certain scenes have stayed with me; in the gap of nearly two decades, I seemed to always know what was coming. But I realised something else: it’s actually in the space in between the grim reality of Reed’s real-life experiences, and Hardwicke’s use of the tropes of mainstream filmmaking about teenage girls – the shopping montage, the sleepover, the front lawns, the mum who acts more like a friend – that these girls start to feel real. The power of that film isn’t really in its efforts to shock: it’s in the combination of a true record of girls’ experience, and the adult filmmaking apparatus that provides the pages for that record.

Thirteen is one of many films appearing on screens again as part of a new girlhood-themed season at the BFI, Seen & Heard. Taking post-2000 girls’ coming-of-age tales as its subject, the programming has a thread of co-authorship running through it. When it comes to girls’ stories on screen, especially those told by women, collaborating with girls more directly has become one way for women’s filmmaking to assert an identity separate to patriarchal film history.

One standout work that has shown a new way for women filmmakers to work with teenage girls is 2020’s Rocks. Directed by Sarah Gavron and starring non-actors from in and around Hackney schools, it tells the story of Rocks (Bukky Bakray), and what happens in the days after she goes home to find her Mum is no longer around to look after her and her brother. When it finally got a cinematic release in autumn of that year, much was made of the film’s importance as a mirror: a mirror that didn’t just reflect, but enlarged its teen-girl protagonists. There is a big-ness to the 20 foot cinema screen, or posters pasted in tube stations, that suggests a raising-up of its subjects – especially when they are those so often ignored, or paid attention to for the wrong reasons, in urban spaces. But when we speak about the power of Rocks, we are speaking about how they got there as much as the fact that they are there: on that billboard, or the Netflix holding page. “Representation matters”, breakout star Bukky Bakray told Dazed at the time. “There are so many marginalised groups missing out on that feeling, and it’s unfair.”

Céline Sciamma’s Girlhood (2014), released just a few years earlier, shares more than a few passing similarities with Rocks – a white female director, spotlighting groups of Black girls living in city estates (in Paris’ banlieues and East London’s council estates, respectively). In both films, the protagonists experience trouble at home that leads them to seek solace in their friends. Neither centre on relationships with boys as their primary “romance”; both are cast with non-actors. However, while Girlhood is beloved by so many – especially for its powerful depiction of the armour friendship offers girls in environments not designed for them to thrive – speaking to the New Yorker last month, Sciamma called Girlhood her most problematic film. For her, it forms part of her early series of films in which she pushed the patriarchal structures as far as they would go, but still worked with, and inside them. She can see now how she was “trying to disrupt the book”, but was still doing so within “the rules of legitimate screenwriting.” If Girlhood does not hold up quite as well to scrutiny now, it’s to do with the less collaborative conditions of its making.

In Rocks, a radically collaborative filmmaking process was pursued. The girls had already been taking part in a series of workshops set up by Gavron and her team, across comprehensives and youth hubs in London, when writer Theresa Ikoko shared her story idea. From there, the entire creative team, including the young cast, contributed to the narrative, with Ikoko and co-writer Claire Wilson inviting the girls to stick post-it notes onto each scene with their feedback (one scene was even reshot after 17-year-old actress Kosar Ali insisted it wasn’t working). What’s more, the dialogue is imbued with the already-forming friendships between the girls, who had got to know each other throughout the process. The result is dialogue that feels lived-in, and that can capture as much of the inarticulacy of girls under pressure – how they feel unable to speak out – as their communal joys.

As Rocks demonstrates, sometimes, it’s not only about seeing oneself on screen, as it is feeling like you’ve been heard. Voiceovers have always been key to providing a sense of interiority in film – it’s when we hear what characters are really thinking about other characters, or gauge the gap between what someone is thinking, and what they are doing. The screenplay of Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978) is unrecognisable without the voiceover of Linda Manz that was added when the film was in post-production: the fifteen-year-old actress was invited to voice her thoughts while watching her scenes back, and the resulting commentary is what gives the previously shapeless plot its forward drive. She comments on the plot, even portends the heartbreak – but she also gives insight into her own inner life. Manz’s voice speaks the doominess of young girlhood that feels like a kind of eternity. “You're only on this Earth once”, she says at one point. “And I – to my opinion, as long as you're around, you should have it nice.”

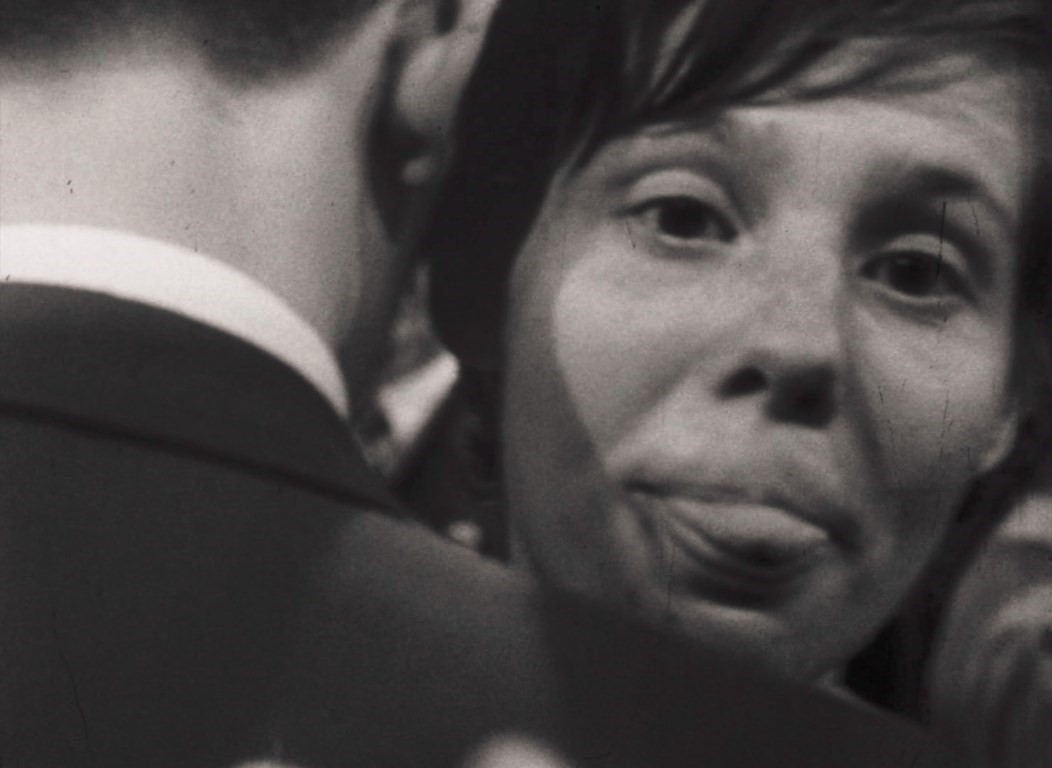

In Věra Chytilová’s wild early work A Bagful Of Fleas (1962), the Czech New Wave director also makes use of voice-over to channel a girls’ perspective into cinema. A window onto young female textile workers living in a hostel together in Soviet Czechoslovakia, the film – described by the director as both a “fictional documentary” and “acted reportage” – blends the real with the made-up from the beginning. Employing non-actors, who improvise their dialogue, to play the girls, Chytilová’s camera is substituted for the gaze of new girl Eva, who narrates her impressions of what and who she sees around her (we never see her face). “They don’t notice me at all,” she says, as she proceeds to wryly comment on the weight, appearance and behaviour of the other girls, who chat over dinner, wave at boys out of the window, and generally steal, jump on furniture and cause trouble. These are girls who are clearly close relatives of the director’s later Daisies duo in their camaraderie and rebellion in an atmosphere of patriarchy – only without the same, surrealist sense of release (or self-implosion).

The fact that many of the best-known female directors begin their career with realistic windows onto girlhood isn’t surprising: Jane Campion (just nominated for her second Oscar), Sofia Coppola, and Mati Diop have also all taken themes of female coming-of-age as their first stepping stone into cinema (the directorial debut: another kind of coming-of-age). Andrea Arnold has threaded a verité approach from the beginning: in her ten-minute short Dog (2001), where a girl experiences a brutal one-two loss of innocence, the casting of unknown actors anticipates Arnold’s lending space to unknown talents like Katie Jarvis (in 2009’s Fish Tank) and Sasha Lane (in 2016’s American Honey). By casting these girls inside their own contexts, and letting them be themselves – simply filming whatever they happen to do – she gives space to a true kind of self-expression. Arnold has stated, “I hate tracking shots. Anything that restricts the camera makes me feel constrained.” That makes sense: I always see her girls as having so much space to dance in, to run wild in – endless Essex flatlands, or wide American plains – even when their emotional life is crunched-down and claustrophobic.

When we question the degree to which the genuine voices, or behaviours, of teenage girls are present in film, we are not only talking about directorial choice – we are also talking about the degree to which the structure of filmmaking itself is allowing that to happen. Techniques of collaboration with girls – co-writing, workshopping, improvising – will always have power when it comes to documenting those more marginalised, and less-seen. Improvised dialogue isn’t new – where there have been cameras, there has always been an ability to capture a spontaneous moment. But there is a difference between working-class girls being themselves on screen, and those from a background where a constant performance of the self is encouraged (the methods of a film like Joanna Hogg’s The Souvenir create their own magic, but they are not doing the same thing).

What’s more, I can’t help but think the move to involve girls more directly in their story must, in recent years, come from a realisation that they are authoring moving images about themselves anyway, and all the time. Girls now hold movie cameras in their hands: it’s in their digital lives that they are constantly improvising – re-making themselves post by post, and moment to moment. The power of a film like Rocks is also the recognition of that fact.

In a landscape where women directors are still taught they have to push and shout to get to the front, to co-write such stories with a teenage girl seems to me an act of generosity – and one which can reshape how we go about making movies in the first place. As writer Theresa Ikoko says of Rocks, to do so, for her, was to create an “ode” to girlhood: “to say that beneath the armour, that the bus driver or the teacher or your work colleagues don’t see, I see the joy and the love and the endless well of complex softness in you, and I want to say thank you and I love you, that I see you.”

The film season Seen & Heard: Daring Female Coming-of-Age Films is at BFI Southbank from 1 February – 15 March 2022. Further films are available to watch in two Seen & Heard collections on BFI Player Subscription, including the Girlhood Studies curation.