As a new film about the frontwoman of X-Ray Spex is released, Nick Levine speaks to the singer’s daughter and the documentary’s co-director Celeste Bell

This riveting documentary film doesn’t offer a revisionist take on Poly Styrene – not exactly, anyway. As the thrillingly idiosyncratic singer driving X-Ray Spex, one of British punk’s most dynamic bands, her place in history is already assured. But it does reframe the late musician’s impact and legacy in a rather more modern way. Billboard might have branded her “one of the least conventional frontpersons in rock history”, but after watching I Am a Cliché, it feels more accurate to call her “one of the most authentic”.

Co-directed by her daughter Celeste Bell, the film takes a personal approach that is well-judged and affecting. “We certainly didn’t want to do a traditional biographical telling of Poly’s story,” Bell’s co-director Paul Sng says. “Over time, it sort of became Celeste and Poly’s story, which is much more interesting.” Bell, who serves as narrator, establishes the contradictions surrounding her famous parent in the very opening frame. “My mother was a punk rock icon,” she says matter-of-factly. “People often ask me if she was a good mum. It’s hard to know what to say.”

Still, with evocative archive footage and excerpts from Styrene’s diaries read by Oscar-nominated actress and former AnOther Magazine cover star Ruth Negga, Bell and Sng definitely capture the spark and unique worldview that made Poly Styrene an instant cult hero. Neneh Cherry, Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna and Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore all sing her praises, but the film doesn’t tie Styrene to what might reductively be called her “1970s heyday”.

Along the way, we also learn about her difficult upbringing in 1960s Brixton. Born Marianne Joan Elliott-Said, the mixed-race daughter of a Scottish-Irish legal secretary and Somali-born dock worker, she never felt fully accepted by either the local Black or white communities. “We were embraced by punk because it was full of people that nobody else wanted,” recalls The Bodysnatchers’ frontwoman Rhoda Dhakar, a fellow mixed-race musician of the era. “We were welcome because we were already outsiders.”

Later, the film explores Styrene’s 1980s years living at Bhaktivedanta Manor, a Hare Krishna temple in the Hertfordshire countryside. But though she changed her name to Maharani during this period and appeared to retreat from the public eye, Bell says it would be a mistake to presume Styrene was ambivalent about her cult status. “I mean, my mum once told me that she had invented leggings,” she says with a smile. “She’d see fashion trends and say: ‘Oh, I did that in 1975.’” Bell says her mother “definitely had a big ego,” pointing out astutely: “You can’t not have an ego, and do what she did, can you? She definitely knew that she was ahead of her time.

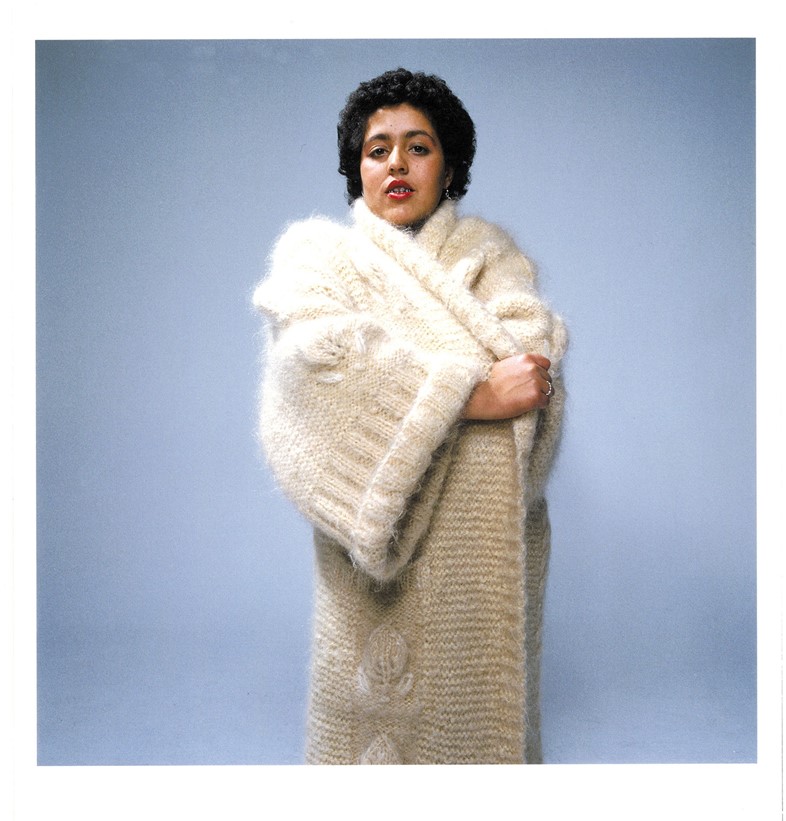

And rightly so – it’s certainly no exaggeration to call Styrene a visionary. “Some people think little girls should be seen and not heard, but I think ‘oh bondage, up yours!’” she speak-shrieks on X-Ray Spex’s seminal feminist anthem, Oh Bondage! Up Yours! Other songs on the band’s classic 1979 album Germfree Adolescents grapple with issues relating to capitalism, public image and identity, which are still relevant today. “I wanna be dehydrated in a consumer society,” she sings on Art-I-Ficial, offering her own surreal brand of social commentary. Styrene’s distinctive dress sense also stood out: unlike other punks, she favoured bright colours and jazzy patterns. She also wore secondhand clothes before they were called “vintage”, and might on stage wear anything from a military jacket to a granny cardigan.

Interview footage from the time reveals the extent to which Styrene was scrutinised and othered by the media for looking different from the era’s mainstream female singers. Even the simple fact that she wore dental braces seemed to become a major talking point. “The good thing about punk is that difference was celebrated, but there was probably too much made of her differences,” Bell suggests. “People were constantly asking her about being a woman, asking if she was a feminist, asking her about race and identity.” Bell says Styrene ultimately felt “fetishised for being different”, which “over time, just added to her insecurity”.

In 1979, an exhausted Styrene left X-Ray Spex and spent several months in a mental health unit after being misdiagnosed with schizophrenia. She continued to struggle with mental health issues for the rest of her life, and was later diagnosed, more accurately, with bipolar disorder. “I honestly think if she hadn’t become famous, she probably wouldn’t have had her first breakdown,” Bell says. “She was someone who was probably susceptible to mental health issues, but I think the trigger for that to manifest into a full-blown disorder was the experience of being in the public eye.” Back in 1979, the music industry hardly supported Styrene through her mental health battles. After watching I Am a Cliché and contrasting Styrene’s experience with that of Britney Spears, a contemporary performer who has also experienced mental health issues, it’s tempting to ask if anything has really changed.

Tragically, Styrene died of breast cancer on April 25, 2011, less than a month after releasing a sparkling new solo album, Generation Indigo. She was just 53 years old. Sng says that while working on the film, he was struck by how many people contacted got in touch to share their cherished memories of the singer. “They say things like, ‘I met Poly once at a train station and we chatted for half an hour – she was wonderful,” he says. For Bell, it’s her mother’s undiluted creative vision that still makes her so fascinating. “The most remarkable thing about my mum is that she never did anything based on the approval of others,“ she says. “I think that’s what makes her really stand out – even from other people we think of as unique.”