Films like Pretty in Pink splashed protagonists’ inner life on the walls of their bedroom – but in 2019, girls’ onscreen bedrooms reflect technology-centric lives

Girlhood Studies: How has visual culture shaped ideas of girlhood? In a new column for AnOthermag.com, Dazed’s editor Claire Marie Healy considers overlooked moments of coming-of-age on screen.

In the summer of 2002, when I was 11 years old, we moved house. From that point on I began plastering my new bedroom wall with the printed matter that represented who I was, or how I saw myself. It was bigger and colder than my childhood room; as winter approached, I remember thinking the collage might serve as useful insulation, a kind of reinforcement against puberty. I recently found a folder on a very old hard drive called ‘Claire’s Stuff’ which reminded me of this. Inside are hundreds of photos – webcam photos, digital-camera selfies from a time before we used that word – most of which were taken in my bedroom. Alone in there, with the door locked and self-timer on, I took photographs of myself, in front of other photographs. It was my set design: never-finished, shifting according to my tastes.

Much like the aesthetics of old teen movies, the images of my bedroom wall also serve as a time capsule. There’s the Spring/Summer 2007 Chloé campaign, before Anja Rubik cut her hair; spreads from Lula magazine and of course Dazed & Confused; Odeon cinema stubs; Rosemary’s Baby-era Mia Farrow; postcards from the all-ages concerts I frequented, with bands like Black Lips and The Horrors. Eventually, when my parents separated, I scrubbed the wall clean for the new buyers. I didn’t live there anymore anyway.

One thing that struck me is the similarity, layout-wise, between my own room and Jules’ in Euphoria, Sam Levinson’s teen drama that aired this year. The ceiling forms a triangular alcove, and light comes through the window which overlooks the bed. But the bedroom of Jules (Hunter Schafer), a new-to-town trans girl who comfortably wears sky-high kilts, glittery make-up, sparkly backpacks, and has pink-streaked hair, has starkly unadorned walls.

Separate from the family home, and school, a teenage girl’s bedroom has traditionally been her only private space. Adrienne Salinger explored this idea in her seminal series, In My Room: Teenagers in Their Bedrooms, which documented boys and girls from various backgrounds in their rooms. I’ve interviewed Salinger a couple of times, and each time she’s expressed her feeling that filmmakers have consistently use her book as a reference, without crediting her. “I was trying hard to address the way that people define themselves, to somehow allow coming of age to be scrutinised in a way that defied cliche,” she told me. “Before then, I felt strongly that the only images that existed of teenagers were from an adult’s perspective, and the power differential bothered me.”

The results of this power differential, when it comes to the movies, is the bedrooms of 80s and 90s Hollywood films, when the ‘teen’ genre came into its own (the undoubted peak, as I mentioned in my first column, being 1999). The idea that, in real life, bedrooms are the visual expression of a girl’s interiority, has long made their appearance in films a shortcut to teen-girl characterisation (often, in bad films, it pretty much replaces it). Though less frequently updated these days, teenagebedroomsonscreen.com has been documenting adolescent bedrooms in the movies for years. There, you’ll find all the usual tropes (music posters, photo collages, mirrors, diaries, a phone) as well as some that have introduced key idiosyncrasies of some of cinema’s greatest teen heroines. Think: the burger phone in Juno, Clueless’ virtual wardrobe from the future, or the opening scene of Terry Zwigoff’s Ghost World, where Thora Birch’s character is seen dancing madly to Jaan Pehechaan Ho from the Bollywood movie Gumnaam on her box-set television, a clip framed within her window frame.

Perhaps the peak of Hollywood’s bedroom-as-interiority rule is Pretty in Pink (1986), John Hughes’ New Wave-soundtracked tale of Andie, a working-class girl who embarks on a seemingly ill-fated first romance with a “richie” – a prep called Blane, whose family has money, unlike Andie’s. That Andie’s bedroom embeds in your memory of the film is probably because so many of its integral scenes take place there: the opening credits, where she gets dressed and applies make-up in a series of extreme close ups; her waiting by her telephone for Blane to finally call; and the scene where she confronts her father, played by Harry Dean Stanton, for still loving the mother who abandoned them (the greatest teen bedroom of all time calls for the greatest teen dad of all time to be on the other side of that door). But from the film’s opening in a grim Chicago neighbourhood, it’s clear the bedroom is Andie’s world, where the dreams that are so much larger than her reality live with her, in her things and her thrifted clothes and her tiny objects. That the film pays attention to Andie’s things is its strength: we believe in her fullness. This is unlike Blane, whose room is American Psycho white, with a single Edward Hopper poster and a matching white phone. As Masha Tupitsyn reflects of the 80s in her essay Mixed Signals, if the preps in linen suits seem empty it’s because they’re not really being teenagers. “Wearing grown-up clothes was a way of being tied – primed – to the conventions of the world even before you were emotionally and chronologically prepared to be primed for them... through your clothes, you could look like the authorised world.” (For Blane, the same goes for his bedroom).

Now, it’s through social media that teenagers primarily interact with the ‘authorised world’: your phone and laptop is the final frontier between you, in your bedroom, and everything else. And as filmmakers interpret how technology intertwines with girls’ lives, so too have the girls’ bedrooms had to change. Two very different works that have handled the same problem this year were Bo Burnham’s Eighth Grade and, of course, Euphoria. Eighth Grade is the story of Kayla, a highly anxious 13-year-old for whom social media seems a double-edged sword: it both offers a way out of her daily reality and serves as a stone-cold reminder of her outsider status, fuelling her anxiety further. But even in a film which takes social media as its subject, Burnham knew the bedroom had to feel real. “I always found kids’ bedrooms in movies to be very fake to me,” he said when I interviewed him earlier this year. “It always felt like you had a blank room and then you decorated this room to perfectly reflect the character, and that, to me is not what a kid’s bedroom is. A 13-year-old’s bedroom is an eight-year-old’s bedroom meets a nine-year-old’s bedroom, meets a ten-year-old’s bedroom. You’re constantly just stacking shit on top of each other… by the time you’re 13, your room is just a mess of random things from your past, and the glow-in-the-dark stars you put up five years ago, and tried to tear off and didn’t.” Maybe she would like to have nice clothes, and nice things, but the environment Kayla can curate most readily isn’t her bedroom; it’s her social media, which Burnham depicts as a multi-sensory, immersive environment. Awash with music and moving images, for the viewer, it’s a total rush to the head – an artificial high on loop.

When Kayla dives in to the social media experience, she’s depicted as ignoring what’s actually around her; for Burnham, social media is clearly a world teenagers enter into, at the expense of real interactions (compare how much time Andie gives to her dad in Pretty in Pink compared to Kayla). But in Euphoria, technology isn’t an optional tool for teenagers, or even a primary plot device (though it’s sometimes that, too). It’s a reality as real as their high school corridors or school gym or bedroom: they inhabit it always, like a parallel world. That they’re not emotionally primed for what happens there – in Euphoria, leaked sex tapes, nudes, bribery, catfishing – is all part of contemporary coming of age. Incorporations of phone and internet-use in teen dramas have rarely been as successful as Euphoria, and much has been written about what it gets right about how teenagers self-actualise through their encounters online: the happy, the empowering, and the extremely dark. This does strange things to the girls’ bedrooms, things we haven’t necessarily seen before – what kind of space does the bedroom offer, in a post-iPhone age? For Kat (Barbie Ferreira), who graduates from writing online fanfiction to cam-girl work for money, the bedroom is where she interacts with strange men online. It becomes her set: invaded by the outside world but only because she has invited it in, while keeping it at a distance with her fetish wear and mask. Eventually, the fantasy turns sour, and her season storyline winds up with her shutting the laptop screen in favour of a chance at real romance, in a space she can’t directly control: real life.

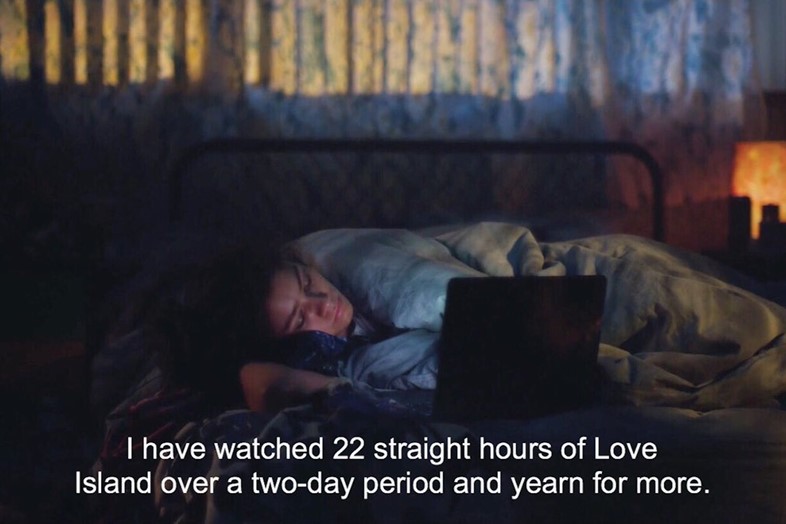

For Rue – Euphoria’s protagonist, played by former Disney Channel child star Zendaya – her room becomes a trap: a manifestation of the depression she falls into in episode seven, where she is too depressed to leave her room to pee, instead watching 22 hours of Love Island straight and giving herself a kidney infection. With shadowy branches against the window pane, piled up alien objects, and extreme close-ups of Rue’s unwashed, glittering face under the covers, the room becomes almost a Disney-fied definition of a scary place; but by making her manic episodes and depression so big, all within that one room, Levinson is also respecting it.

Euphoria suggests that bedrooms aren’t only a safe space, where “girls can be girls”; they’re a trap, a playground, an arena for fantasy, or, as with new-to-town Jules, a blank slate that she intends to keep blank. Just like the deeply-felt approach to clothes in the show, the show offers a new flexibility to what bedrooms do for teenage characterisation – how it can architect their emotions – rarely seen in the highly stylised tropes of those in other shows.

Around the time I was ruining my bedroom wallpaper, I was using Flickr, MySpace and Blogspot to share my tastes. They felt like like-for-like versions of the bedroom wall, parallel zones, but for an audience: both imagined and increasingly, actual. Tavi Gevinson’s Rookie magazine came a little later, but similarly strove for an at home, in-your-bedroom aesthetic: the first editor’s letter included an image of Gevinson’s busy dressing table, and outlined the site's aim to post three times a day, “roughly when school ends, when dinner starts and when it’s really late and you should be writing a paper but are Facebook stalking instead”. But as audiences become the environment, and teenagers’ awareness of monetising their interests heightens, the third space isn’t just physical anymore. It’s on our phones and laptop screens, where you can show the world you are part of it. You’re primed.

Of her teenage subjects in the 80s and 90s, Adrienne Salinger told me once “a teenager only has that 12 by 12 feet. [That’s why] everything has to fit in there: the past and the future.” But as our film and television screens are starting to reflect back to us, other spaces are in the frame.