Now considered a classic of the silent era, Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc is a surprisingly radical take on the tale

A visitor to the film set of The Passion of Joan of Arc during its production in 1927 would have been perplexed by what they saw. In Danish auteur Carl Theodor Dreyer’s reconstruction of Joan’s trial, nothing was as it seemed: the walls of Rouen Castle were painted pink, holes pockmarked the studio floor, and medieval manuscripts were littered everywhere. Adopting a radical shooting style which would dazzle even by contemporary standards, there was an unconventional method to Dreyer’s madness; the pink set appeared as a lovely chiaroscuro grey in the film, the various holes allowed for his iconic, low-angle shots, and the manuscripts were recreated to lend an authentic touch. With the Criterion Collection releasing a restored version of The Passion of Joan of Arc this March, a new audience can witness the film’s timely exploration of institutional hypocrisy and spiritual division, as well as understand its chequered behind-the-scenes story.

A silent retelling of the French 15th-century teenage martyr, little about Joan of Arc’s story or history is predictable. Joan’s ordeal is rendered largely in close-up; sentenced by an all-male ecclesiastical court, Joan is bullied into denouncing her faith, before being burned at the stake, and eventually becoming the canonised idol of lore. One of the film’s few panning shots – a sea of men raising their hands to seal the fate of a young woman – chills with its unfortunate contemporary resonance. Compressing her 18-month interrogation into a single scene, the script was based on the actual transcripts from the trial, allowing the film to shun the melodrama of standard period pieces.

This was hardly the biggest challenge facing the film. On its initial release, despite holding critics in raptures, the film was a financial flop, and Dreyer struggled to find funding for his next project. As Issa Clubb, producer at the Criterion Collection, told AnOther: “This is a film whose original negative was lost to fire; Dreyer’s attempt at a reconstruction was also lost; and those prints that did remain were subjected to some unfortunate edits. Finally, as the famous story goes, an original print was found in a closet in a Norwegian mental institution in 1981, and both our original DVD and this new restoration come from this print.”

In the intervening decades, The Passion of Joan of Arc has opened floodgates of opinions from the 20th-century’s best and brightest. To Jean Cocteau, the film seemed like “an historical document from an era in which the cinema didn’t exist”. To legendary critic Pauline Kael, Renée Falconetti’s performance as Joan “may be the finest performance ever recorded on film”. About its status in the canon of great silent cinema, and in the Criterion Collection, Clubb said: “I’m not sure there was ever any question whether we would include The Passion of Joan of Arc in the Criterion Collection, as it is not just one of the greatest silent films, but one of the greatest films in all of cinema, full stop.”

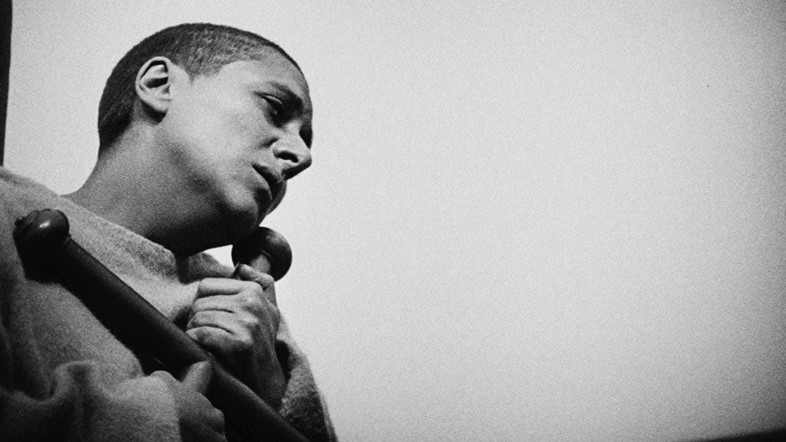

Even today, critics marvel at how unique Dreyer’s vision for the film had been. From the outset, he offers zero exposition, casting us in medias res, narrowing the story’s scope to focus on emotion over history. Strung together, his close-ups of Falconetti equal 23 minutes; a quarter of the film focused on that expansive, expressive face. The large, immaculately recreated sets were never shown off in establishing shots. (The Danish Film Museum, in Copenhagen, now houses the set in its entirety – towers, chapels, courtrooms and all.) The panchromatic film used shows skin in a naturalistic light, with Dreyer opting to shoot Joan in a soft, even lighting – in opposition to the high-contrast film frames used for the jurors, quite literally exposing their warts. Dreyer makes us feel the jurors’ gaze by framing tightly on Falconetti’s face, his static camerawork crafting a mosaic of faces.

This avant-garde camerawork jars our instinctive response to cinematic storytelling – we demand context, and understand a language of shooting that favours wide shots or panning shots. Dreyer’s ‘cinema of stasis’ goes against the language of cinema itself in a way few films ever have. The visual cues we typically crave are absent, as Dreyer’s symphony of close-ups instruct us how to feel; giving us emotion as action. Eschewing make-up, Dreyer also wanted to avoid the ‘beautification’ so commonly tied to religious iconography. Joan is no gilded heroine or angelic creature, Dreyer opting instead for a humanist approach: finding the divine in the mundane. Long before Rothko commanded 1950s society to seek God in his floating fields of red, Dreyer asked us to consider divinity from our most familiar canvas – the human face. Yet he also manages to sidestep the homogenous morality of martyrdom – his version of Joan is passionate, ecstatic, and human.

90 years on from release, festivals still screen The Passion of Joan of Arc annually, often accompanied by orchestras, vocal groups, and bands for special screenings (this would be well received by Dreyer, who was reportedly never content with the film’s final score). Falconetti died in 1946, having never starred in another film. Dreyer died in 1968, his great, aspirational project – a film about Jesus Christ – never making it to screen. With the Criterion Collection’s restoration, however, audiences can connect anew with The Passion of Joan of Arc, the saint’s face beaming brighter than ever.

The Passion of Joan of Arc, The Criterion Collection edition, is available to buy from March 20, 2018.