What does the zeitgeist of British art look like at the moment? A bold, eclectic new group show at Hauser & Wirth Somerset, Present Tense, aims to answer this question, showcasing the work of 23 artists both emerging and mid-career. With a mix of sculpture, painting, drawing, collage, video, and installation, there’s much to take in: fresh from his ICA solo show at the end of last year, there’s the uncanny, colourful sculptures of Gray Wielebinski; glitchy, tumultuous compositions by George Rouy; sensual collages by Ebun Sodipo, vast, cinema-inspired painting by Joseph Yaeger; a series of hallucinatory pigment dye transfers by Sang Woo Kim depicting glowing figures in nature; and much more.

Although there’s a fair amount of sculpture in the show, painting reigns supreme here, ranging from the abstract, angsty canvases of Daisy Parris, all the way to the figurative, confrontational work of Victoria Cantons, which deals with the artist’s lived experience as a transgender woman (Parris’s work draws obvious parallels to Tracey Emin, and Cantons to Jenny Saville – two titans of British art). As a contemporary survey of emerging British artists, in theory, the ’next’ Emin and Saville are in this Hauser & Wirth show, too.

Speaking a few days after the opening, Isabella Bornholt, the show’s curator, says she’s noticed a real return to skill and craft in the art of recent years. “All the artists in the show have real conceptual gravitas to their works, but they also execute it with a skill,” she says, “which I think is very much indicative of what’s happening in the art world right now.” Another key theme that emerged, she believes, is self-reflection. “In a world where we consume so much imagery and information on a day-to-day basis via our phones and our laptops, it’s a really new, hyperactive way to live,” she says. “And so many of these artists are looking inwards and self-reflecting to pose and answer questions.”

As a mega-gallery with locations in London, New York, Paris, Zurich, LA, Hong Kong and more, Present Tense offers an exciting opportunity for younger artists to show at Hauser & Wirth – none of whom are currently on their roster – and a refreshing chance to show outside of London, where most of the UK’s art-world action usually takes place. Located in the picturesque town of Bruton, which boasts top-quality restaurants and hotels (Rochelle Canteen’s Margot Henderson does the food at The Three Horseshoes, a 17th-century pub opened by Phoebe Philo’s husband, Max Wigram, last year), a weekend trip down to Somerset to see the show is well worth the journey.

Below, five artists featured in the show – Victoria Cantons, Joseph Yaeger, Ebun Sodipo, George Rouy, and Sang Woo Kim – talk in their own words about their work.

Victoria Cantons

“An ongoing idea I explore in my work is: what’s my place in the world? All my works are about the same thing, ultimately. It’s all about: how do I deal with the world around me, and with the people around me? And inviting the audience to look at the same questions and conversation for themselves.

“Good Fortune or An October Flush depicts the moment when I had my bandages removed after I had facial surgery to feminise my appearance. I transitioned at the age of 38, so I’d had a good 30 years of testosterone affecting my body and adding masculine appearance to my face. As a transgender woman in my thirties, I was getting abuse every single day I went out the front door. Sometimes they might be polite, but very often, it was more a case of, ‘Hey, you. What are you? You’re a man in a dress.’ That’s a polite version of what I got. And worst of all, every morning I got up, I looked in the mirror and I saw a face that I knew was me, but wasn’t me. I had a face that looked male but I was female. So I was going further and further into depression, both on a personal level in terms of just facing my own appearance, and what I was dealing with from the world around me, that just couldn’t accept who I was.

“I had the opportunity to undertake facial surgery and I did. It was a major investment and a major risk, because I didn’t know what the end result would be. I was 11 hours on the operating theatre – you don’t know if you’re going to wake up again. You’re putting your trust completely in the hands of this surgeon, who is basically saying, ‘I’m great, you’re gonna look fantastic. Trust me.’ The surgery was transformative because no longer did I look in the mirror and see a male face looking out at me. No longer did I walk down the street and get given abuse on a daily basis. Yes, I still had occasional experiences which were negative, but on the whole, I could be far more a part of society than I’d ever been before.“

Joseph Yaeger

“Once, always is watercolour on gessoed linen, and is a cropped image of a person in some sort of threshold with their head brushing against a partially reflective surface – a wardrobe, say – so that the ear reflects back on itself. On the other side of the composition, the face is being obscured into darkness by a shadow, which fades in a warm gradient. As in many of my paintings, it’s important that the emotions or perceived actions of subjects depicted not be legible as only one thing.

“Much of my work is derived from stills I extract from films. It’s important that I’m not painting from iconic or regularly circulating cinematic imagery, the circulation of which, I feel, by its very nature, assigns language or language-like qualities to an image, which I’m trying at all costs to avoid. My love of cinema dates back to my early teenage years, and was probably a reaction to the cultural isolation I felt growing up in Montana. Watching challenging, slow, or ruminative cinema in those days, which really did feel almost like studying, revealed to me at that incredibly formative age how to, as it were, exist outside of myself, within image.

“The translation into paint I think of as a kind of projection – using my body as a projector, more specifically. The technological elements of the practice – laptop, streaming services, screenshots, Photoshop, etc – essentially end when it comes to the act of creating the painting. I don’t sketch, nor do I use a projector, and I paint on the floor (watercolour would run off the canvas if it were upright), so the image, when everything is clicking, seems to emerge as if by magic out of the pooled paint. It’s genuinely quite mysterious to me – there is very little, if any, conscious or linguistic thought occurring in the act of painting.”

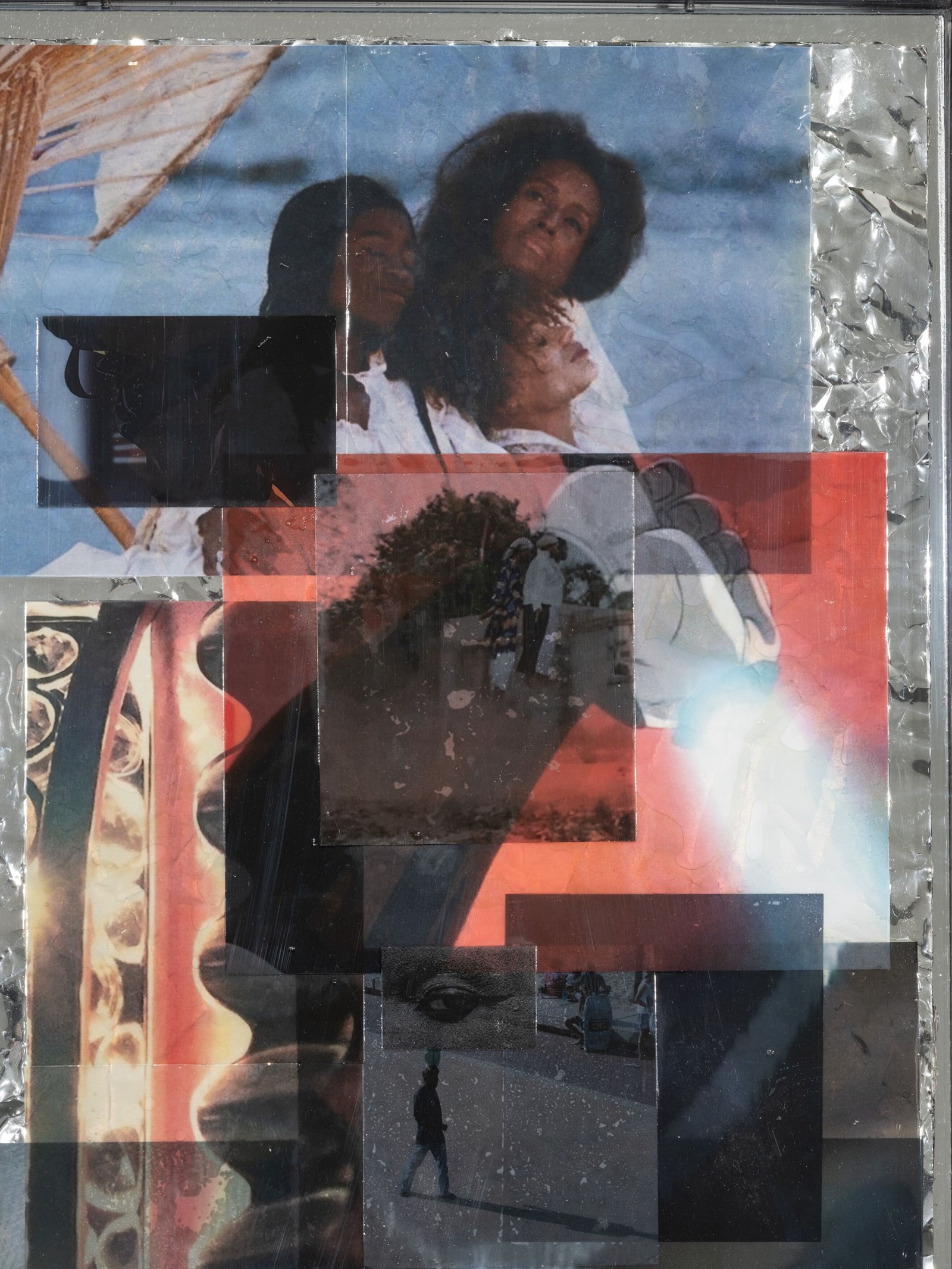

Ebun Sodipo

“I pull the images for my collages from this archive I’ve been building since 2014. From 2014 – 2018, I would go on Tumblr for a certain amount of time every day, and I would collect anything that was posted by a Black person that came across my feed. I basically grew up online. Tumblr kind of determined what it meant for me to be Black. It informed my politics when I was younger, and it’s a place where I found myself, so that context is really important.

“These collages are about trying to describe a particular emotion, thought or desire that I have. I also like to think about the ways that we use these images and the Internet to communicate with each other, and to determine who and what we are through this relationship that is mediated by images. These images impact you in a way that you can’t describe. It’s like pre-thought; you don’t really think about them, you feel them.

“Water, the sea, and the Atlantic is a really important aspect of my practice. I started making this work thinking about what it means to be Black, and part of that has to do with the Atlantic, or now, in contemporary times, the Mediterranean and the Gulf. I am thinking about what happens when a body moves from Africa into a non-African space via the sea, and the kind of transformations that happen. The psychological phenomenon of looking at the shifting feel of light and water, the kind of meditative states that it can get into, is really interesting to me. There’s a theory that one of the reasons why we are drawn to shiny and glittering surfaces is because they remind us of water on a deep instinctual, lizard-brain kind of level. Our body is trying to quench a thirst that has been with us for a very long time, but you can never actually quench the thirst, and the desire is deeply embedded in your body in your DNA. That suddenly becomes a metaphor for thinking about transness and transfemininity, and this desire to move the body or to follow the desire to a certain point. That’s why I use the motif of water and reflective surfaces in shine and shimmer, to get your attention and draw you in.”

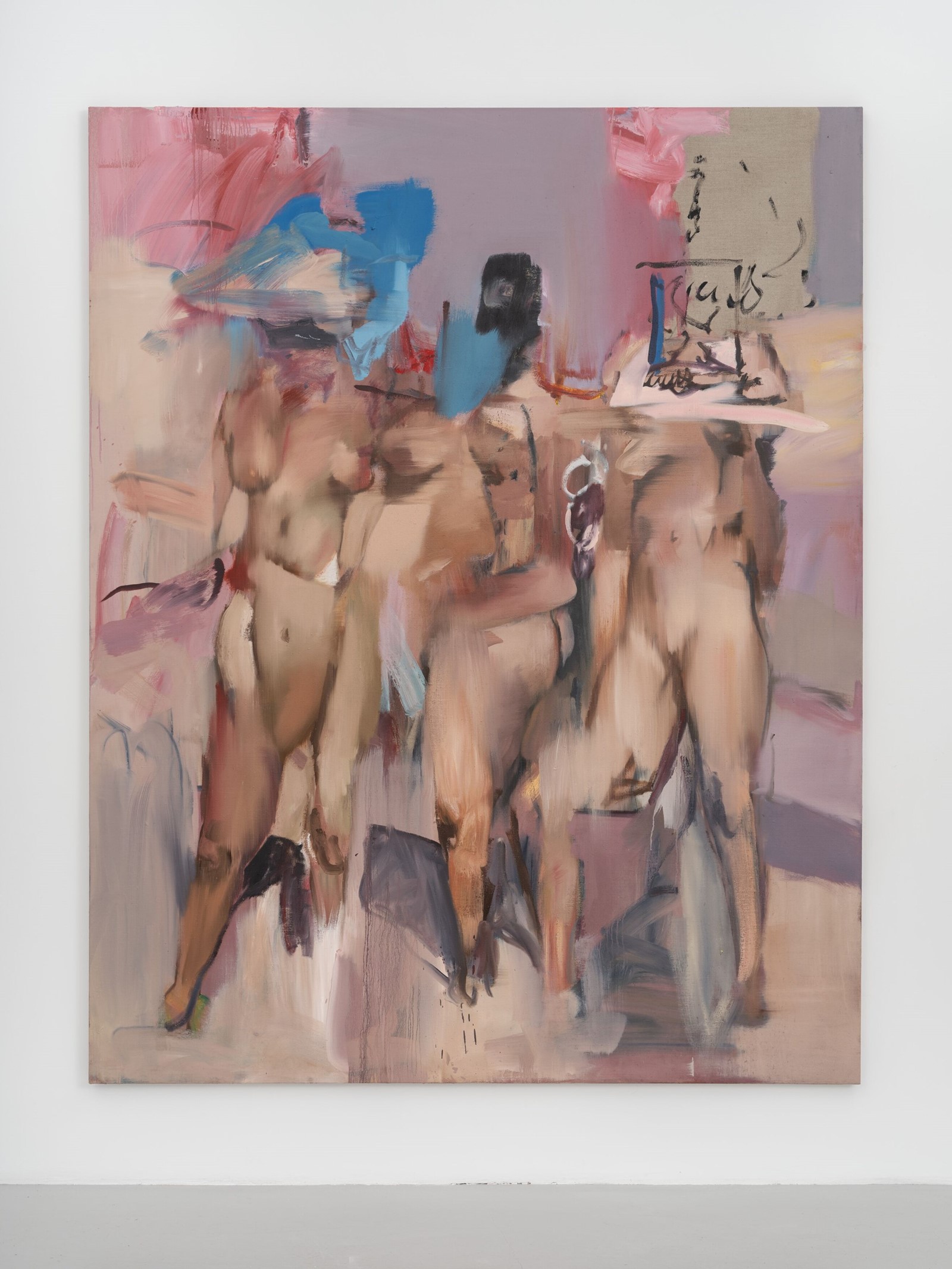

George Rouy

“I wanted my paintings in the show to feel like they commanded a bit of a different treatment than my other works. They feel a little bit more political. I see Dissimulated Nude as having a hood or a balaclava. There’s a bit more violence to it. On the top right hand, there’s a square, and I see that as a framed area where a face would be, or facial recognition. There’s always things in the work, but you don’t want people to just read it in one way. The paintings are supposed to be a catalyst for an intuitive response to something, without having to think about it too much.

“We’re living in such an intense time, it feels odd to just be like business as usual. The work is a way for me to process and explore certain things, without it being too heavily political or specific. I think we’re all ready for intensity. Or maybe the world is so intense, we don’t want it. I’m not quite sure. Do you seek refuge in the more subtle things in life when the world feels like it’s too much? Or does it go the other way, when things become more extreme? I don’t know if there’s a need for extreme work at the moment, because all you have to do is switch on the news and it’s pretty much there.

“When I make work, usually I piece together a set of paintings on Photoshop, collaging found images, inspiration, and I create a kind of mini-series. I’ve always been into found imagery, or the idea of using what’s there and re-appropriating that in a Duchampian way. The Internet is this spectacle of information, a pool of unlimited resources when it comes to that. There’s so many images, and piecing those together as a painting can be quite beautiful. These are just the ingredients though – I want the paintings to be seen as individual works that are detached from certain realities.”

Sang Woo Kim

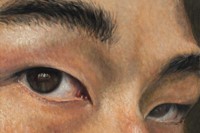

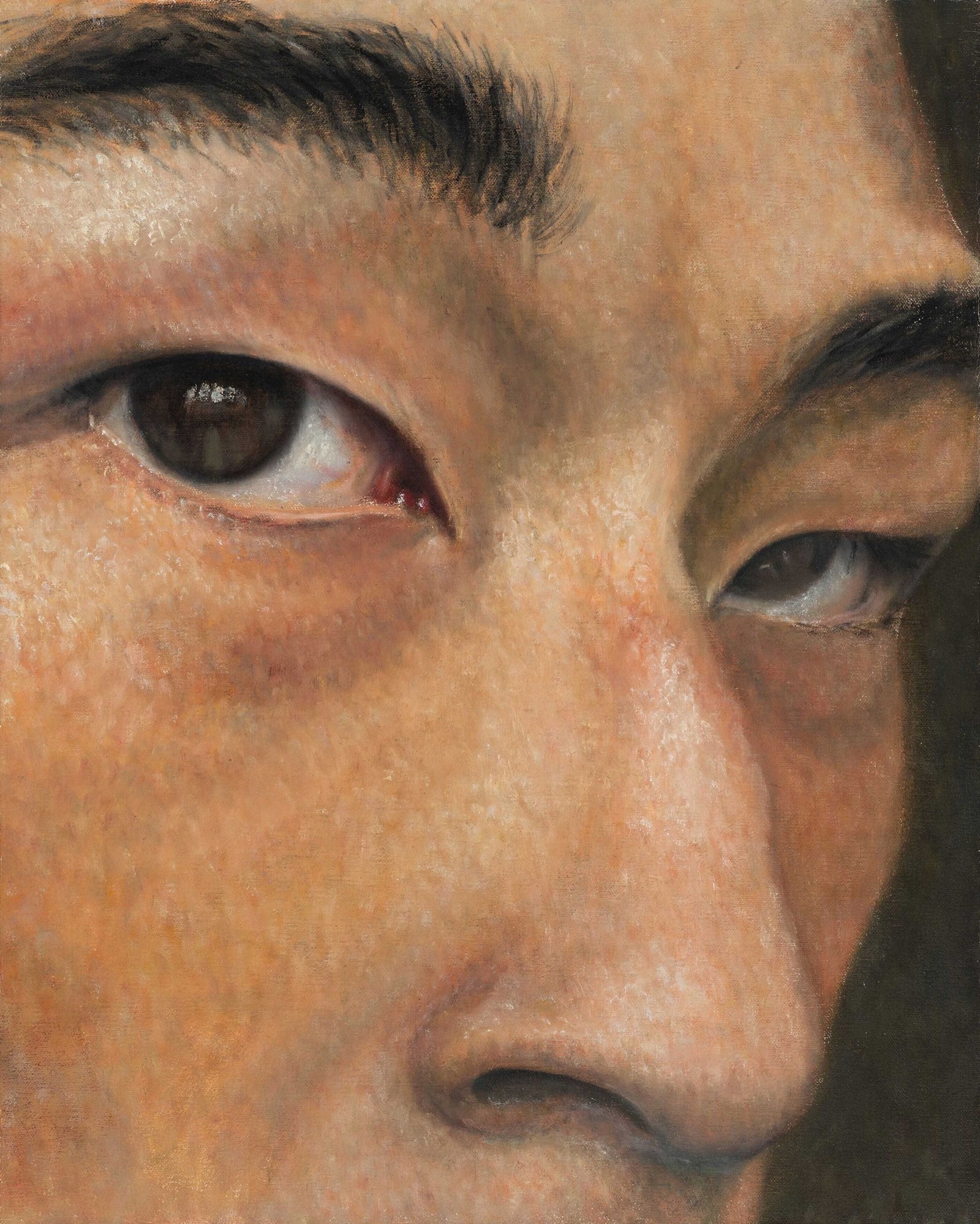

“All of my work is autobiographical: it’s about the being, the self. I create to be able to gain a deeper understanding of myself and in turn, to comprehend the world better. The self-portrait paintings featured in the Hauser & Wirth show delve into my experience of discrimination and racism rooted in the way I looked growing up in the Western gaze. They explore the journey from the challenges of racial bias to the reclamation of my image and identity, a struggle intensified by my role as a model with no agency over my image and identity. This juxtaposition creates an internal conflict that I aim to overcome by confronting myself through these self-portraits, to accept, and to be.

“‘The slit you made’ painting in the show is a self-portrait focusing on a section of my face with a black eye. It’s a provocation to the viewers, who are predominantly Western, since I was discriminated against for having ‘slitty’ or ‘no eyes’. The bruise metaphorically represents the enduring pain that has shaped my entire life. This bruise however has made me who I am today, and I’m now able to tell these struggles (of otherness) to the world through my art.

“I use the pigment transfers to reflect an 'inward' gaze, using imagery as analogies or metaphors for my state of being, the mind, and the soul. The Blindspot series in the show depicts this void, a glowing silhouette in various landscapes or scenes. It’s a representation of self-discovery and spirituality. The question I ask is: Who or what is this void? Does one see themselves or do they see me? Is it a ghost or is it an angel? Are they the same thing?”