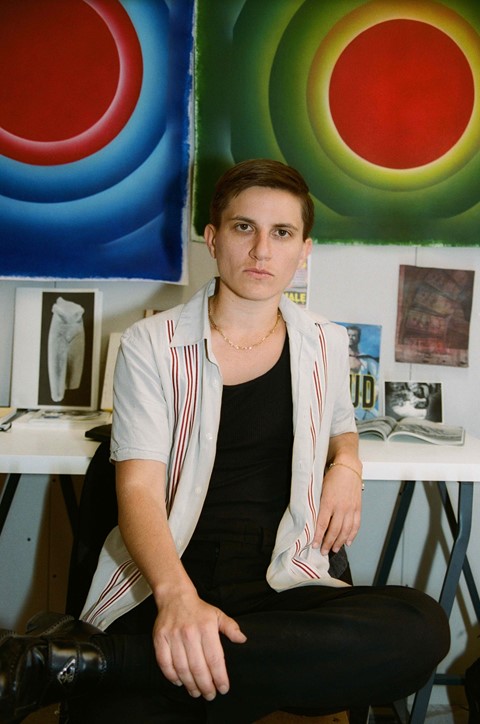

As his new solo show opens at the ICA in London, Gray Wielebinski talks about the anxiety that can accompany living through late capitalism, life during and after a pandemic, and climate change

“We’re collectively comfortable exploring post-apocalypticism – think of zombie movies,” says the Texas-born artist Gray Wielebinski, who is based between London and LA. “I am interested in focusing on and sitting within the pre-apocalyptic, and the accompanying feelings of paranoia, waiting and unknowing.”

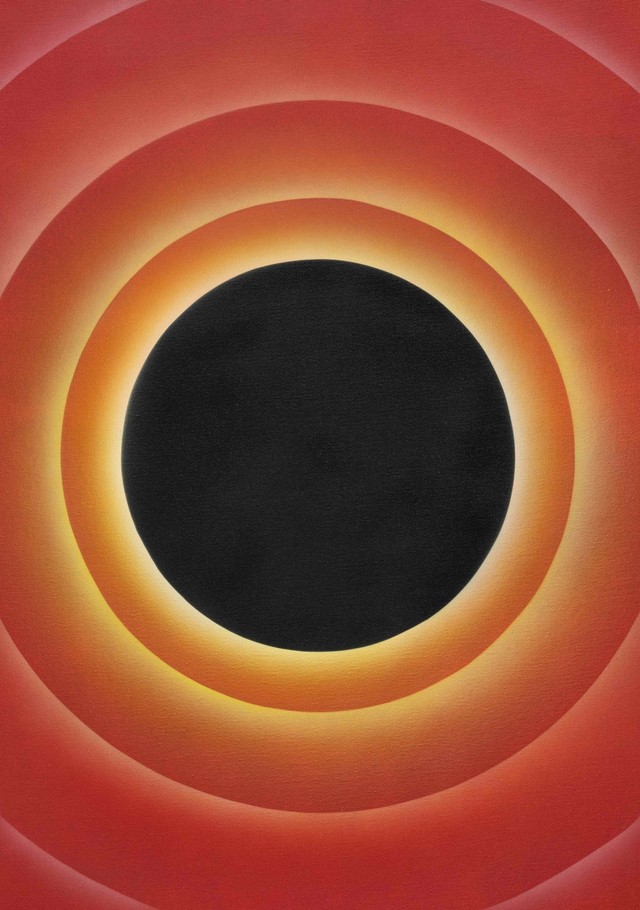

At Wielebinski’s newly opened solo show at the ICA in London, The Red Sun is High, the Blue Low, the sound of cicadas buzzes in the air, while a white-noise-like sound installation conjures the artist’s childhood in Dallas. “They make me think of summer and hanging out outside as a child, but they also sound menacing, like a siren,” says Wielebinski. One wall of the show is lined with six images of rising suns borrowed from Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s 1982 film Querelle, a sci-fi-inflected reference leaving it unclear as to whether the same sun rises six times, or whether we are in a world with six suns of its own. In the centre of the space, an architectural seating structure brings visitors together, facing one another in a huddle, while at the back of the room is a dark bunker from which you can view the rest of the exhibition through a peephole, encouraging an alternate perspective. Above all of this, a looming basketball court scoreboard watches over guests as though they are in a game, although the rules are unclear. Together, the elements can be interpreted as playful or sinister, depending on how you look at things.

The show is Wielebinski’s take on the present moment – ”pre-apocalyptic” – and the oscillation between amnesia and anxiety that can accompany living through late capitalism, life during and after a pandemic, as well as climate change.

Although broader in scope and more referential than Wielebinski’s previous work, it builds on longstanding themes and interests. One is the ways in which we interact with private and public space. Last year, Wielebinksi’s installation at Selfridges – a threatening metal sculpture entitled Exhibition – referenced public bathrooms and the contentiousness of those spaces, especially for trans people. 2022’s Pain and Glory at Bold Tendencies in Peckham, meanwhile, saw Wielebinski create a large-scale installation on the roof comprising a mechanical bull (you could ride it) surrounded by a metal structure with glory holes. These forays into creating public art commissions drew on the language of architecture. Pain and Glory, in particular, was a way to re-engage people with public space off the back of lockdown, in which its precarity became more pronounced on top of existing issues like gentrification and policing. It was a reprisal to the threats made to public space by private and commercial space, in a time when property ownership is positioned as the only means of survival in an increasingly hostile outside world. A time when, in Wielebinski’s own words, people are “sequestering themselves and sanitising their experiences for comfort, as the division between those with private wealth and property with those who don’t have it widens.” In other words, bunkering down.

Enter the ICA show: a continuation of these ideas, with new interactive elements that Wielebinski “hopes aren’t gimmicky, but provoke a sense of affect or presence” as well as communality. Site-specific, the show responds directly to the ICA’s position on The Mall and its proximity to Buckingham Palace (its own kind of private bunker), St James’s Park (a private-turned-public space), and the Admiralty Citadel – the ivy-covered building opposite the ICA that was built in 1940. “You can’t go inside it,” says Wielebinski, “because it’s still a functioning Ministry of Defence building, but it contains a bunker, and – apparently – tunnels that go to Whitehall”. With access denied, references in The Red Sun is High, the Blue Low imagine what’s behind closed doors; the seating area is Wielebinski’s war room, the peephole his telescope, the bunker his nuclear shelter.

If 1991 (the year Wielebinski was born) marked the fall of the Soviet Union, the alleged end of communism, and the moment capitalism was destined to prevail, aren’t we just living in a new age of paranoia, accelerated capitalism bringing us back to square one: the fear of apocalypse? This is one question The Red Sun is High, the Blue Low leaves you pondering. “I think paranoia is important, in unpicking – particularly in America – state mythmaking, narrativising and control. We see this heightened in the prevalence of conspiracy theories now, and I think it’s symptomatic of a society that is making people feel unwell or unsafe or unprotected. That’s why all of the works in the show have this shimmering meaning, going from being light and fun to dark and confusing … because that’s how I feel as well, quite paranoid but also ambivalent.”

With this in mind, it’s little surprise that Todd Haynes’s 1995 film Safe has made it onto the screening programme Wielebinski has curated to accompany the show. The film stars Julianne Moore as the housewife who contracts an unknown sickness that could be caused by pollution or consumerism. As well as the screening programme, the space will play home to a series of talks, performances and workshops throughout the duration of Wielebinski’s exhibition. The artist deliberately did not want to give too much direction, but allow the practitioners “a lot of space and liberty to respond to the atmosphere and set up”. If Wielebinski’s work interrogates the “call to remember, embrace and also mourn the public experience of being together”, it’s also a reminder that art itself can do the opposite: bring our bodies into contact in space.

The Red Sun is High, the Blue Low by Gray Wielebinski is on show at the ICA in London until 23 December 2023.