The British Council’s commission Dancing Before the Moon at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2023 confronts the UK’s history, but sets out an optimistic vision for its future

It’s hard to feel positive about Britain right now. 13 years of Conservative rule, Brexit, the pandemic, the cost-of-living crisis, among a myriad other factors, have made this a fairly relentlessly exhausting place to live. It often feels like a country hellbent on its own destruction. A place in perpetual decline, like a dead spider swirling around the plug hole as water drains out of a bath.

I sometimes feel like this country is like a man who refuses to go to therapy, despite desperately needing it; a man who is delusional about his own size and importance; who thinks he’s a good guy despite pretty obviously being the bad guy; who doesn’t know who he is or how to reckon with his past, which is at once great and shameful; a man who is ultimately quite sad, frightened, lost and confused.

Exiting the British Pavilion exhibition at the Venice Biennale of Architecture earlier this month, I felt a glimmer of optimism. Commissioned by the British Council and curated by Jayden Ali, Joseph Henry, Meneesha Kellay and Sumitra Upham, this exhibition features work by six brilliant artists – Yussef Agbo-Ola, Mac Collins, Shawanda Corbett, Madhav Kidao, Sandra Poulson and Ali himself, all of whom are of dual heritage – and explores the relationship between diaspora community rituals and cultural practices, and space; how architecture might be able to shape the future of the UK.

The exhibition borrowed its title, Dancing Before the Moon, from the great James Baldwin, who wrote: “There is a reason, after all, that some people wish to colonise the moon, and others dance before it as an ancient friend.” It speaks to the two diametrically-opposed relationships we can choose to have with the world: one defined by domination – by abuse, exploitation, extraction – and one defined by friendship.

“In many countries, the moon is celebrated as a symbol of life,” say the curators. “To us, the quote reflects a longing and appreciation for global rituals and everyday practices that demonstrate an appreciation of soil and the cosmos. It proposes an alternative way of considering collective relationships to land and geography, and how communities come together to hold space through making and social practices. Importantly it speaks to both the past and the future.”

Entering the British Pavilion, visitors are greeted with Ali’s work – a vast metal sculpture titled Thunder and Şimşek that hangs above the entrance. Exploring his ancestral links to the islands of Trinidad and Cyprus (both of which were colonised by the UK), the piece is made using steel hammered into shape, a nod to both the pastimes of Trinidadian steel pan-playing and Cypriot cooking. From there, they are met with a film that looks at the rituals performed by the global diaspora in Britain – from archive footage of Notting Hill Carnival to new footage from a pub in Nottingham and a hair salon in Streatham.

Further into the exhibition, there are rooms devoted to each artist. Their works fill the spaces, which are quite moderately sized, forcing people to move around them, much as they, the curators say, as people of colour are forced to move around whiteness and Englishness in Britain. They took up space, literally.

Sandra Paulson’s installation, Sãbao Azul e Água, for instance, took the form of a colonial-era balustrade, rendered with a blue soap called sabão azul, that is ubiquitous in Angola, where Paulson grew up, but in other countries too, such as Brazil. It also features a cement tank used for hand-washing clothes, a garment that recalls a traditional Angolan dress, and some footprints – which belong to her grandmother. It speaks to Paulson’s memories of growing up in Luanda, as well as the nation’s past under Portuguese imperial rule.

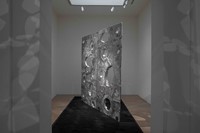

Meanwhile Mac Collins, who is of dual British-Jamaican heritage and is based in Nottingham, presented an enormous, amorphous sculpture hewn from black ash wood. Heavy but at the same time weightless, it seemed to float above its base, which resembles the soft furnishings of his local pub. (It reminded me of the spacecrafts in Arrival, though Collins joked that it looked like Patrick Star from SpongeBob Squarepants). Run by a Jamaican man, this pub has helped Collins connect with his roots – there, he plays dominos (a favourite pastime of Jamaican men) with the regulars. “That space is a perfect amalgamation of how I understand my own culture as a mixed-race person,” he says.

The exhibition seemed to suggest that Britain could be great: if it took its formerly oppressive relationship with the world and turned it into something open, something inclusive; if it took its toxic globalism and changed it – redeemed it – into a positive form of globalism, where Britishness is happily and freely amalgamated with the different peoples and cultures who live here. The artists didn’t offer a pessimistic vision for the UK, or give a kind of culture war vision that would incense Daily Mail readers, but nor did they attempt to gloss over its past. They showed how we can take the good parts of that past, and allow them to inform the future, through an architectural lens.

Elsewhere at the Biennale, countries sought to reckon with their pasts and lay out radical visions for the future, with space – architecture – at the heart of these solutions. Walking around, I was struck by how the two great projects of the 21st century – decolonisation and mitigating the effects of the climate crisis – seem to be about undoing the two great projects of the previous centuries – colonisation and industrialisation, and by proxy, the destruction of the environment. For white, Western countries, there is a reckoning happening: how do they deal with the people and places they once subjugated? Do they deny and defend their legacies or accept and address them? Those responses feel as polarised as anything.

Curated by Lesley Lokko, the Biennale put this great project of decolonisation front and centre. Lokko placed Africa at the fore – more than half of the Biennale’s 89 participants were from Africa or the African diaspora – while the Western nations examined their own pasts and laid out visions for their futures. Australia, Canada, Brazil, among others, explored Indigenous peoples’ relationship to land and space – a hard and heavy task. Brazil won the prestigious Golden Lion for best national participation, having presented “a research exhibition and architectural intervention that center the philosophies and imaginaries of Indigenous and Black population towards modes of reparation”. (Interestingly, America chose not to engage with these themes, instead putting on an exhibition about plastic.)

On the wall of the Brazilian pavilion, the words “the future is ancestral” were written. There is so much there for us to think about in Western countries, as we completely refigure the way we look at the world and how we relate to it.

The 18th International Architecture Exhibition, titled The Laboratory of the Future and curated by Lesley Lokko, is open until 26 November 2023.